|

Author's Preface

|

|

This is an account of the life of a Colonial Administrator whose career spanned almost the

last fifty years of the British Empire. I wrote it because I believe it is important to be able to

refer to real life accounts in order to fully understand historical events. I also have a personal

reason. William Leslie Heape was my father. As father and son, we belong not only to

different generations, but also to different epochs; He to the Colonial Period and I essentially,

to the Post-Colonial Period of this country's history. However, I believe my perception of

that earlier period has been considerably enriched by my knowledge of my father as a man of

his time. It is that knowledge, which I hope to share with you through this personal memoir.

The events described are chronologically accurate, but the opinions expressed about

historical events are my own, written many years later with the benefit of hindsight. I have

some personal knowledge of parts of his life, because I spent my early childhood with my

parents in the West Indies, but I have had to rely on my own research, and what my father

told me for the rest of the story.

|

|

Introduction

|

|

When he first joined the Colonial Administration in 1919, W L Heape could not have had any

inkling that his career would span almost the last fifty years of the Service. The two World

Wars in the first half of the 20th century brought about a dramatic change to this country's

status as the most powerful nation in the world. At the end of the 1st World War, most people

still believed in the might of the British Empire. As he watched Marshall Foch on his irongrey

charger, with Admiral Beatty and Field-Marshall Haig on either side, riding at the head

of the Peace Parade in London in 1919, Heape's feelings of pride and elation at the sight of

this magnificent procession were never again equalled in his life. Nobody imagined that the

sun was setting on the Empire then. But after the 2nd World War, Britain found the burden of

ruling the Empire too great, and by 1960, Prime Minister Harold Macmillan had decided to

grant independence to most of the Crown Colonies.

In the Nineteenth Century, an earlier generation of the Heape Family had taken advantage of

the opportunities to trade overseas, created by the expansion of the British Empire in the

Victorian era. Benjamin Heape, William Leslie's grandfather, went out to Australia as a free

man in 1839, and established a business in Melbourne. In partnership with his five brothers,

they purchased a sailing ship and traded in both Australia and China. Leslie Heape and his

elder brother Charles Heape were both attracted to a career overseas. Charles Heape went out

to India in 1910 and chose a career in commerce at the Calcutta Stock Exchange. He made

and lost several fortunes in the heady days of the British Raj. Leslie Heape, who was never

attracted to a career in business, applied to join the Colonial Administrative Service on being discharged from the Army in 1919. All applicants had to pass an interview and his first

interview was conducted by the redoubtable Major Ralph Furse. Having stated that he could

ride a horse, he was offered the job as Assistant Secretary to the Governor of British

Somaliland. That was beginning of 14 happy years in Africa. Serious illness in 1933 very

nearly ended his career in the Colonial Service. He was told that he could never return to

Africa, unless he had his wounded leg amputated. He refused to have further surgery, and had

no option but to retire from the Colonial Service. However, this forced retirement did not

mark the end of his Colonial Career. Sir Mark Young, the newly appointed Governor of

Barbados, offered him an appointment as his Private Secretary, and with that opportunity, he

began the second part of his career in the West Indies.

Heape was one of that brave generation of young men, who fought so courageously for King

and Country in the First World War. Many of his contemporaries at school including his best

friend were killed, and he was left disabled for the rest of his life. His courage and the high

moral values, which he learnt at Rugby School, helped him to overcome all the vicissitudes

that beset him throughout his life. His Housemaster at Rugby, G F Bradby, said of him; "He

bore a very high character, conscientious in the performance of all duties, cheerful and

reliable, with considerable tact in dealing with men, and able to come to clear and quick

decisions, in every way fitted for posts of responsibility and trust. " The Headmaster, the

Reverend Dr. A David also gave him a very good character reference saying, "Heape's

record here is excellent. He was cheerful, reliable and sociable, and will be a good man to

work with." Although he had served for a very short time in the Army, his Commanding

Officer, Brigadier-General Scott-Kerr, had the highest opinion of him, as a conscientious,

hard working officer, who had lots of initiative and was always willing to accept

responsibility besides being tactful and good mannered. General Scott-Kerr said that Heape

was always cheery and given to making the best of things under all circumstances. These

were his testimonials when applying to the Colonial Office in 1919.

Later in his career, many people commentated on his integrity and his concern for the welfare

of local people. The resolutions of the Executive Council of the Bahamas and British Guiana

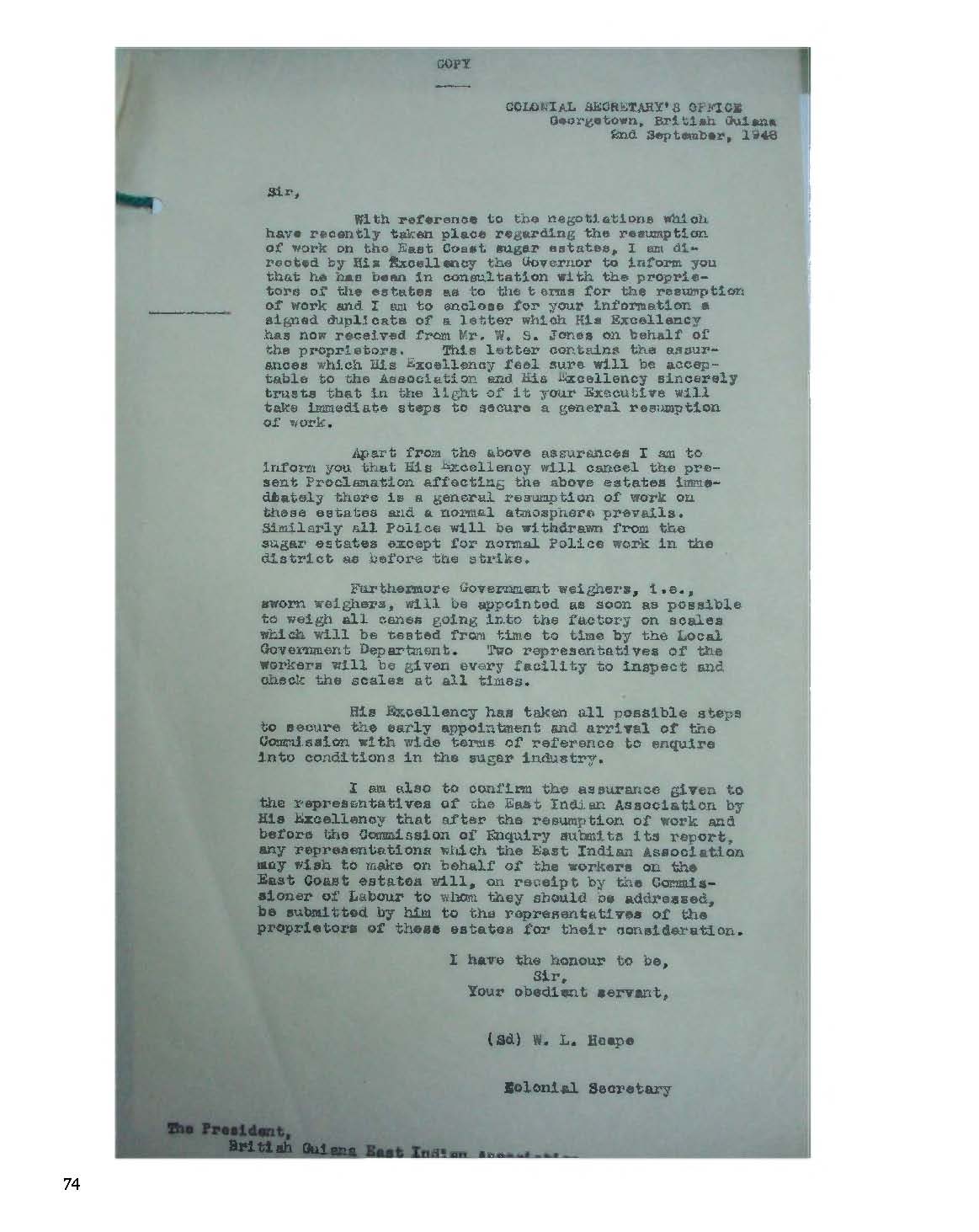

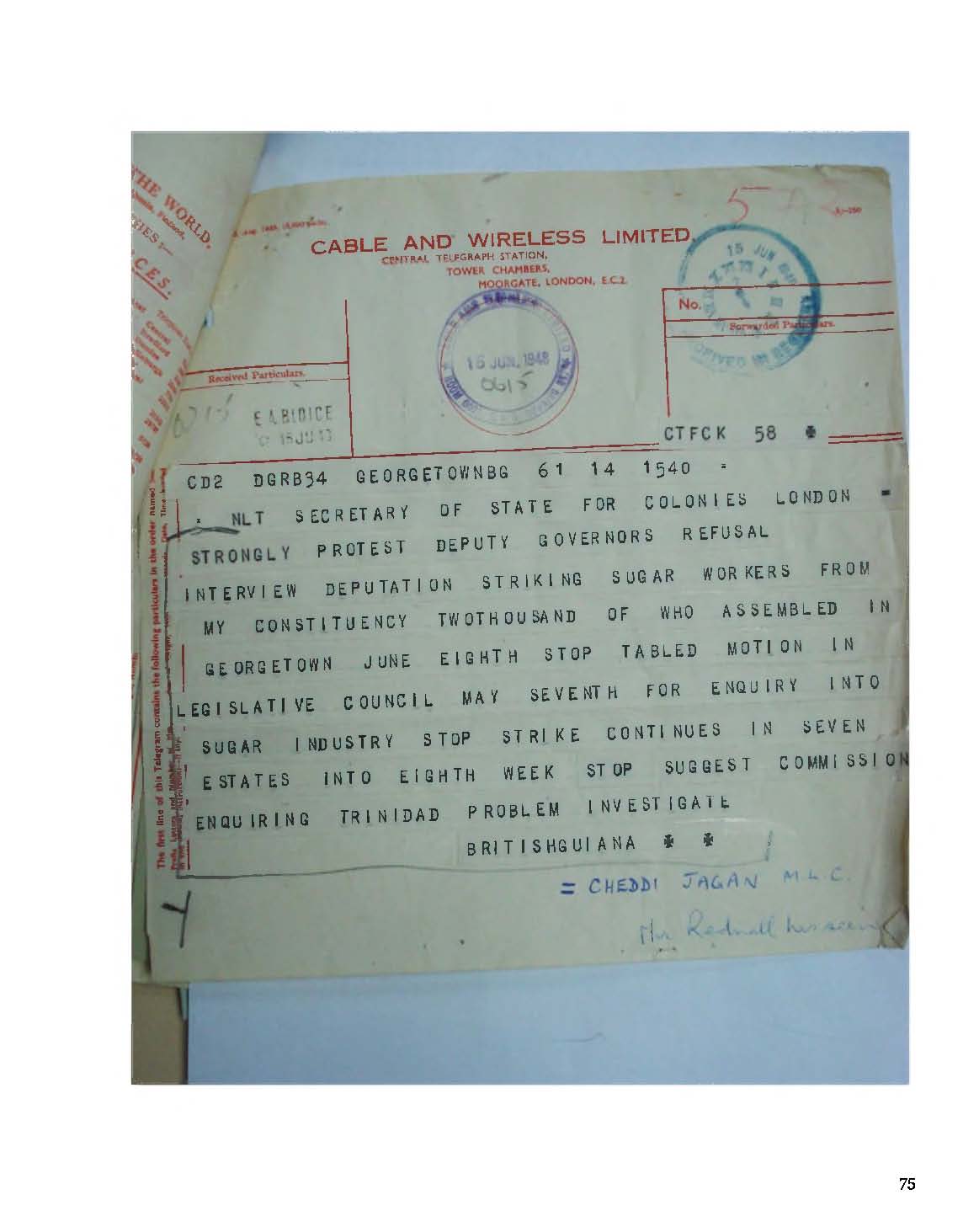

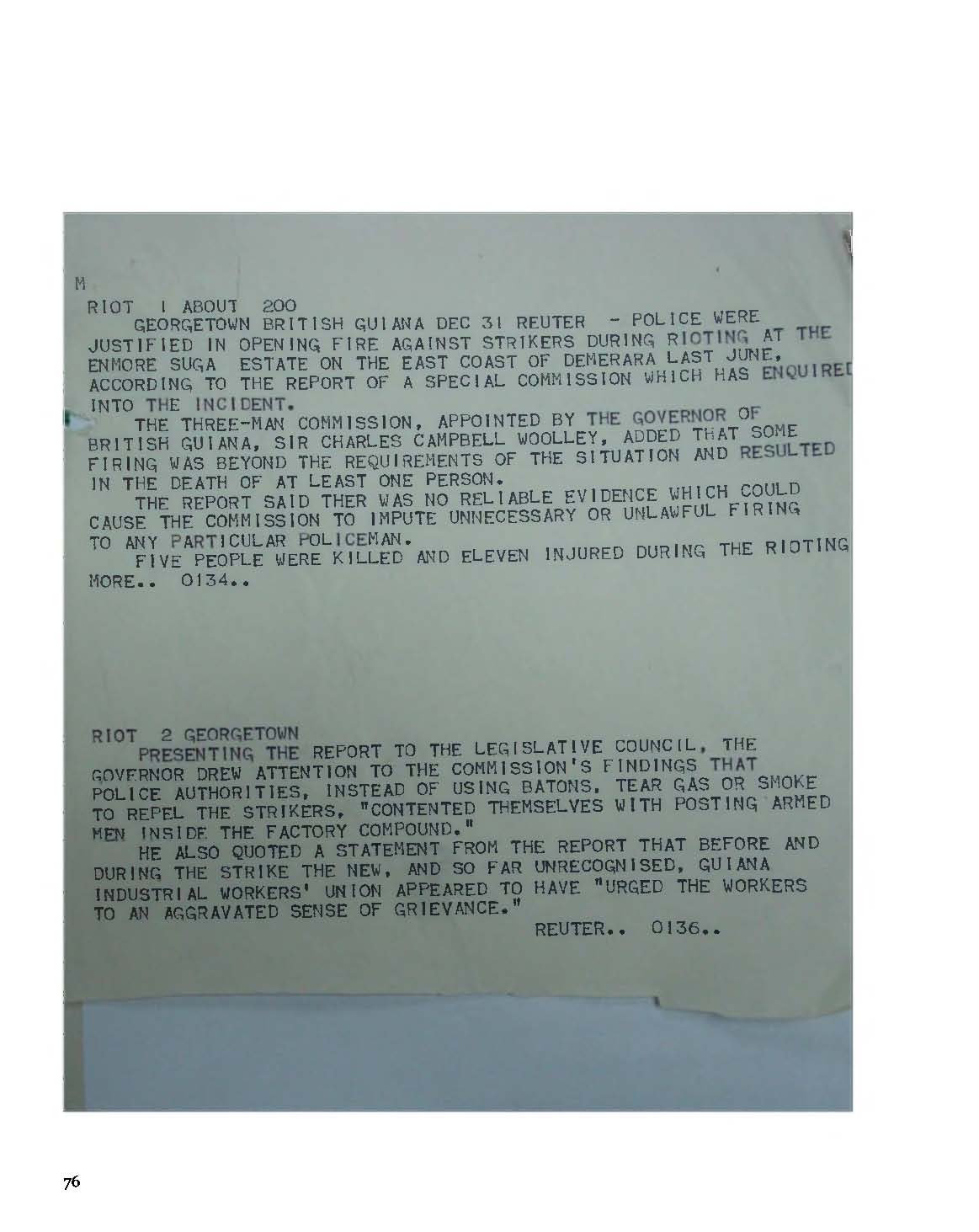

for his work in both colonies was clearly expressed: Bahamas Resolution and British Guiana Resolution

He attended the coronation of King George VI in 1937, and was awarded the Coronation

Medal for his contribution to the community of Grenada. He was also justly proud to have

been made a Companion of the Most Distinguished Order of St. Michael and St. George in

1942. The CMG (Latin motto "Auspicium Melioris Aevi" meaning 'Token of a better age') is

awarded for rending extraordinary or important non-military service overseas.

Leslie Heape was a straightforward Edwardian with a warm sense of humour. He was a fine

example of the traditions of the Colonial Service combining a strong commitment to the rule

of law with humanitarian values. He never hesitated in taking difficult decisions. His doctor, who had known him for the last 14 years of his life, told his wife that Heape was one of the

bravest men that he had ever known. He never lost his pride in the British Empire and the

era of Pax Britannia. He epitomized the British Colonial Administrator about whom, the

philosopher George Santayana writing his Soliloquies in England in 1922 said; "Never

since the heroic days of Greece has the world had such a sweet, just, boyish master. It will

be a black day for the human race when scientific blackguards, conspirators, churls and

fanatics manage to supplant him."

|

|

His Early Life

|

|

William Leslie Heape was the youngest son of Herbert Heape and Edith Jessie Heape, nee

Agnew. His father was a barrister on the Northern Circuit, and William Leslie was born on

5th August 1896 in Manchester. He was educated at Rugby School, which he attended from

1910 to 1913. He then entered the Royal Military Academy, at Sandhurst in August 1914, his

father having signed the application form for his son's admission to the Academy on 29 June

1914. His father had to pay the sum of £150 for his son to go to Sandhurst. He received his

commission into the East Lancashire Regiment in December 1914, after only six months

Officer training. He was sent to France to join B Company of the 2nd Battalion of the

Regiment on 12th April 1915, and was severely wounded in the left leg at the Battle of

Aubers Ridge on 9th May 1915. His wounds became gangrenous in France, and he was

transferred to hospital at 17 Park Lane in London, where he was treated by the Australian

Surgeons Sir Douglas Shields and Sir Alfred Fripp. He had to spend more than a year in

hospital. He was then seconded to the Royal Flying Corps as an Equipment Officer in 1917,

and spent the remainder of the war working in the War Office in London. He was placed on

half pay when the war ended, as he was considered permanently unfit for General Service in

the Army. He was lucky to survive the effects of the Clostridia infection of the muscle tissue

in his leg, which developed into gas gangrene. As a result of his wounds, he suffered from a

permanently stiff left leg for the rest of his life. He could never run again, but he managed to

swim, ride horses and motorbikes, and drive a car with the full use of only one leg.

|

|

His Career as a Colonial Administrator in East Africa

|

|

Heape applied to the Colonial Office in 1919 and was offered a posting to British

Somaliland. He was still only 23 years old. He was excited by the thought of going there,

remembering the article he had read about the death of Captain Corfield in the Illustrated

London News in 1913. Later, he became convinced that Corfield had been unfairly blamed

for disobeying orders, and he took the trouble to send his version of the story to the Bodleian

Library fifty years later:

"I am recording this story as it was told to me, because the death of Capt. Corfield in

Somaliland had a not inconsiderable influence in my decision to accept a post in that

territory and in the words of Voltaire: "To the dead one owes nothing but the truth".

It happened this way; when I was a boy of 17, I saw on the platform of Rugby Railway station, a photograph of Capt. Corfield under the heading "British Reverse in Somaliland

Camel Corps Disaster". That was in August 1913. I read an account of the action and it

puzzled me. I became interested in the resulting political controversy, which nearly brought

down the Liberal Government of the time. The Colonial Secretary in reply to attacks from

the Conservative opposition, sheltered behind the explanation from the Commissioner of

Somaliland that Capt. Corfield had brought disaster on his own head by exceeding his

instructions and penetrating too far into the interior without adequate support. Two years

later, I was lying severely wounded in 17 Park Lane Hospital being entertained by stories

from the famous General Carton de Wiart, who had just come home wounded in action

against the Mad Mullah in Somaliland.

At the end of the war, when the Colonial Office offered me an appointment in that territory, I

accepted with alacrity and in 1919, I found myself serving directly under Governor Geoffrey

Archer, who as Commissioner sent Capt. Corfield on that fateful expedition in 1913.

Col. Summers was then commanding the Camel Corps and I very soon realised that he was

on very bad terms indeed with the Governor; they were hardly speaking. In due course, I

heard this astonishing story from someone, who claimed to have read Archer's confidential

dispatch to the Secretary of State in 1913.

The British were then administrating the coastal strip only and Archer was gradually taking

over the interior. He was in camp some way from lower Shweilk with Capt. Corfield and his

constabulary when Gerald Summers, then a young Captain of Indian Cavalry, joined them on

leave from the coast. Archer suggested to Summers that he should go with Corfield on a

reconnaissance and enjoy some shooting. The party set off and ran into the main force of the

Mullah. The friendly tribes ran away; Corfield was killed. Lt Dunn gallantly withdrew the

remnants of the Constabulary with Gerald Summers gravely wounded. It was then that

Archer sent off his confidential dispatch, which is alleged, blamed Corfield for the disaster,

50 years have elapsed. All concerned are now dead, but the dispatch is open to examination

to confirm the truth, if thought necessary. "

W.L. Heape

In 1909, His Majesty's Government had instructed the Commissioner of British Somaliland

to abandon control of internal affairs over the tribes in the interior of the country, and

concentrate on administering the three coast towns. This policy had resulted in disorder and

fighting between the Dervishes, commanded by the Mad Mullah, and the local tribes. The

Secretary of State for the Colonies, Lord Harcourt, eventually agreed to the setting up of a

small force of Camel Constabulary consisting of 150 men divided into two companies under

the command of Captain R C Corfield, for an estimated of cost £7,950. In 1912, the

Commissioner of British Somaliland, Mr H A Byatt, instructed Corfield to garrison the town of Burao, 90 miles inland of Berbera. On the instructions of the Secretary of State, Mr Byatt

specifically ordered Captain Corfield to avoid engaging a large force of the enemy. Mr Byatt

went home on leave in June 1913 and Geoffrey Archer took over as Acting Commissioner.

On 6th August 1913, Archer went to Burao to discuss the Dervish threat with the local tribal

elders. He was accompanied by Captain G H Summers, the Commanding Officer of the

King's African Rifles. It was reported that a large force of Dervishes had crossed the border

and were raiding cattle belonging to the friendly tribes. Archer ordered Corfield to

reconnoitre the area to gather intelligence, but warned him not to engage a large force of the

enemy. He instructed Summers to accompany Corfield.

On 8th August 1913, Captain Corfield, accompanied by Mr C de S Dunn, his second-in-command

and Captain Summers set out on the road to Ber with a small force of 116

constables and some friendly tribesmen to investigate the reports. Captain Corfield decided to

intercept the large force of Dervishes, estimated to be about 1,500 strong, to prevent them

from driving the stolen cattle over the border. A battle took place on the morning of 9th

August at a place known as Dul Madoba (the Black Hill), during which Captain Corfield was

killed.

The Acting Commissioner sent the following telegraph to the Secretary of State reporting the

incident, which was received in London at 9.10pm on 10th August 1913:

August 9th. Burao. The Camel Company, during a reconnaissance between Ber

and Idoweina, were severely engaged to-day by a dervish party, the strength of which is

estimated at 1,000 men, which was believed to have been advancing on Burao. I have

received no official report, but two Camel Company men bring news. I deeply regret to report

that Corfield has been shot dead and that Dunn is wounded. Sixty men of the Camel

Company are reported dead. It is clear that the Camel Company retreat was cut off and they

therefore zaribaed. The Maxim jammed. The losses both of dervishes and friendlies are

reported to be exceedingly heavy. Firing continues. The rest of the Camel Company cannot

move, twenty-five miles out, so I have no alternative but to proceed myself now with my

Indian escort of twenty men and such friendlies as I can collect and attempt to succour. I am

ordering the Indian contingent at Berbera to proceed to our assistance with a doctor in case

we make good our retreat on Sheikh. I am requesting the Resident at Aden to send 300 troops

at once to garrison Berbera. Please communicate your instructions to Powell - Archer.

All the correspondence with the Secretary of State concerning this incident can be found in

the report "Affairs in Somaliland" dated 1913. At the time, the British Press reported the

incident as a shameful reversal for British Armed Forces, and the Liberal Government of the

day was censured by their Conservative opposition for failing to provide a strong enough

military presence in British Somaliland to govern the country properly. The authorities laid

the blame on Corfield for damaging national prestige by disobeying orders, but to some people he was a honourable man of principle, who had paid with his life, and was wrongly

blamed. A polemic against the Government under the title "The People Without A Pillow"

was published in Blackwood Magazine under the pseudonym Zeres. This is the controversy,

which Heape was referring to. He was also right about the tension between Sir Geoffrey

Archer and Col. Summers as correspondence between Mr Stachey and Sir Masterton Smith

in London confirmed, (ref: CO 536/66 National Archives). Col. Summers succeeded Archer

As Governor of British Somaliland in 1922.

Shortly before he died, Heape also wrote down the following account of his arrival in

Somaliland in 1919:

"I was soon invited for an interview at the Colonial Office, and was seen by Mr Sidebottom

and Mr Furse. I explained that the War Office would release me at once and very soon

afterwards, I was instructed to see Mr Jardine, who was Secretary to the Government of

British Somaliland at the time. We met in the Colonial Office Library. He asked me about

my work at the War Office and whether I had had any experience of coding and ciphers. I

said "no" and told him about my work with the Highland brigade, which was entirely

administrative. He did not seem impressed and we had a desultory conversation. It was not

a good interview. Jardine was scholarly, mature and critical; I was young, confident and

brash. We did not like each other and I was told long afterwards that Jardine did not want

me. But I received another invitation, this time from the Governor of British Somaliland, Sir

Geoffrey Archer, who invited me to lunch at Jules. This interview went much better. It all

seems very odd now when one thinks of the complex procedure that built up for recruiting

officers for the Colonial service. Immediately after the First World War, however, the

Colonial Office were wanting recruits badly, and Governor Archer's opinion must have

outweighed Jardine's, because soon after my second interview I received an official offer,

subject to medical fitness, of an appointment as Assistant Secretary to the Government of

British Somaliland on a salary of £250 pa rising by annual increments of £20 to £500 a year.

I am not quite sure of the salary scale, but it was around those figures and at the time seemed

very generous to me. Somaliland! This was Corfield's country and I remembered the picture

of him I had gazed at in 1913. I also remembered the stories General Carton de Wiart had

told me in hospital about his Somaliland experiences.

It seemed an exciting country, as indeed it is. I thought a bit about Jardine, but I decided to

accept very quickly, and I may say now that I have never once regretted that decision. After

a very shaky start in Somaliland, Jardine and I eventually became firm friends in Tanganyika

Territory.

However, my stiff leg nearly did for me. I passed my first medical examination and then I

was told to report for another examination. This time the Doctor informed me that I would

have to spend much time on horseback in Somaliland. He asked me whether I could manage to ride with one knee stiff. I had never ridden, but I took a chance and said, "Yes". The

Doctor accepted my assurance and I was finally passed fit. In fact, riding never did present

any difficulty. The Somali ponies generally had an easy action and no one attempted to post

at the trot. One simply sat with a relaxed back and jogged along, and in no time you found

that you could cover miles and miles without discomfort or fatigue. I kept the same sweet

tempered pony for all my ten years service in Somaliland and got a great deal of pleasure out

of riding, though I never was good enough to play polo. I rode mainly by balance and the

only trouble was the constant friction on the scar tissue on the inside of my damaged leg,

which eventually set up inflammation of the bone. To my dismay, I landed up on leave in

Queen Mary's Hospital at Roehampton again for a bone scrape. Since I left Somaliland, I

have abandoned riding for that reason.

I made a quick visit to my parents at Southport to tell them the good news. They were a trifle

startled, as they had no idea what I was going to do, but they were soon delighted when I

explained that I had secured a beginning of a worthwhile career. I travelled out by British

India steamer in a three-berth cabin with a newly joined Police Officer, also bound for

Somaliland, and another man, who was going out to Ceylon in some post connected with

Fisheries. We soon found out that he was drinking heavily. He had a mild attack of the D.

Ts. one night and we reported him to the Purser, who did his best to control his supply of

alcohol without success. The poor man continued to see things and we learnt later that he

shot himself in his cabin. Thank heavens he waited until we left the ship at Aden.

We spent one night at Aden in a ghastly hotel called Fishteins and embarked for Berbera the

next day in a 90 ton steamer named S.S. Woodcock, a cargo boat belonging to the firm of

Cowasjee, Dinshaw & Sons. The "Woodcock" carried an English skipper, but all the other

hands were Somalis and she was navigated and steered very competently by Somali Serangs.

We slept on the bridge with the skipper. We had an uneventful crossing and arrived at

Berbera next day. But the passage could be very uncomfortable during the South West

Monsoon, and during my ten years service in Somaliland, I experienced some very rough

passages between Aden and Berbera.

I think I must have made my first landing about November 1919, because I remember that the

Governor and Secretary were up at Sheikh. I spent my first night in Berbera as guest of the

District Commissioner R.R.H. Jebb. No one could have given me a warmer welcome."

W.L. Heape

Sadly, this is where Heape's own account of his life in the Colonial Service ends. Illness

overtook him in 1970 and he did not write any more, but he told my sister and I many stories

about Africa, especially after a good dinner. He served as Assistant Secretary to the

Governor of British Somaliland for 10 years from 1919 to 1929, and I think he must have turned down promotion to stay there, because he liked the life so much. It was certainly a

unique and fascinating part of Africa in those days. Richard Francis Burton and John

Hanning Speke were the first Europeans to explore the hinterland of Somaliland in 1854.

The wild tribesmen, who inhabited the country, attacked them. They returned in

1856 to look for the Great Lakes and the source of the River Nile further inland. They were

the first Europeans to explore the Horn of Africa and they discovered Lake Tanganyika and

Lake Victoria. Somaliland was teaming with wild animals in the early days and hunting was

the ulterior motive for most of the early European explorers such as Harald Swayne, who

surveyed much of the country in the late 1880s. In his book First Footsteps in East Africa

the explorer, Sir Richard Burton, described the port of Berbera in 1848 as: "the perfect Babel

with merchants from as far a field as Muscat, Bahrain and Bombay coming to the annual fair

there. Disputes between the tribes were settled by the spear and dagger. Long strings of

camels arrived daily, escorted generally by women. Groups of dusky, travel-worn children

marked the arrival of slaves from Harar". Berbera was certainly a colourful place in those

days. It became the seat of government in my father's time. The British had claimed part of

Western Somaliland around the trading ports of Berbera and Zeila when the Egyptians left in

1884. The port of Aden on the other side of the Gulf had been garrisoned with British troops

from India in 1839, and the market at Berbera supplied the garrison at Aden with meat.

Heape must have travelled out to Aden by British India Steamer in November 1919. I still

have his original passport dated 13th October 1919, with endorsements giving him

permission to land in Malta on 25th November 1919, and at Aden on 4th December 1919.

When he first arrived in 1919, Mr Geoffrey Francis Archer was the Governor of the

Protectorate, and Major A.S. Lawrence, who was Heape's immediate superior, was in charge

of the Secretariat. The country was divided up into five large districts for administrative

purpose, each district run by a District Commissioner. The three coastal districts were centred

on the ports of Zeila near the western frontier, Berbera in the middle and Khoria sixty miles

along the coast to the east of Berbera. There were two inland districts administered from

Burao and Hargeisa. In addition to the five District Commissioners and their Assistants, there

were two Officers in charge of the Camel Corps, as well as Public Works Department

officials, and Prisons officers. A high white wall shaded by carefully irrigated date palms,

mimosa trees, hibiscus and oleander bushes surrounded the European quarters at Berbera.

The dozen or so houses within the walls were all painted white. Each house had a large

veranda overlooking the sea. The largest buildings were the Governor's House and the Club.

The description of the European quarters at Berbera comes from Margery Perham's book

Major Dane's Garden.

Margery Perham travelled out to Somaliland by sea with her sister Ethel in 1921. Her

husband, Major Harry Rayne, was the District Commissioner at Hargeisa. They finally

arrived at Berbera on 24th January, three and a half weeks after setting out from England.

While waiting to continue their journey to Hargeisa, they were entertained by the Governor,

who invited them to a grand dinner on 3rd February. "Everyone was there" Margery Perham

recorded, and the meal was lavish, with twelve courses including buck, oysters, plum

pudding and champagne. It must have been on this occasion that my father's two pet lion

cubs bit the bare feet of the waiters, causing them to spill drinks all over the guests. It was

one of the stories he related to my sister and I. He got to know the two Perham sisters well,

while they were staying in Berbera, and there are several photographs of them in his

collection of African photographs. They eventually departed on the arduous seven-day

journey to Hargeisa, which meant travelling first by car, then by mule, and finally on ponies

with Ethel's two small sons. She described the journey up the escarpment in the vehicles as

terrifying, the slightest mistake in negotiating the hairpin bends would have plunged them to

their deaths.

Heape could not play tennis or polo, because of his stiff leg, but he acquired a naval sailing

Whaler, which he used to sail along the coast. He took Margery Perham and her

sister out sailing in his boat and she later wrote about a hair-raising sail in a cutter

to Zeila with a young man named Blaker in her novel about Somaliland. Margery Perham

wrote "Major Dane's Garden" soon after returning to England. This first experience of

Africa made such an impression on Margery Perham that she devoted the rest of her life to colonial affairs. She became the acknowledged expert on African nationalism, and was

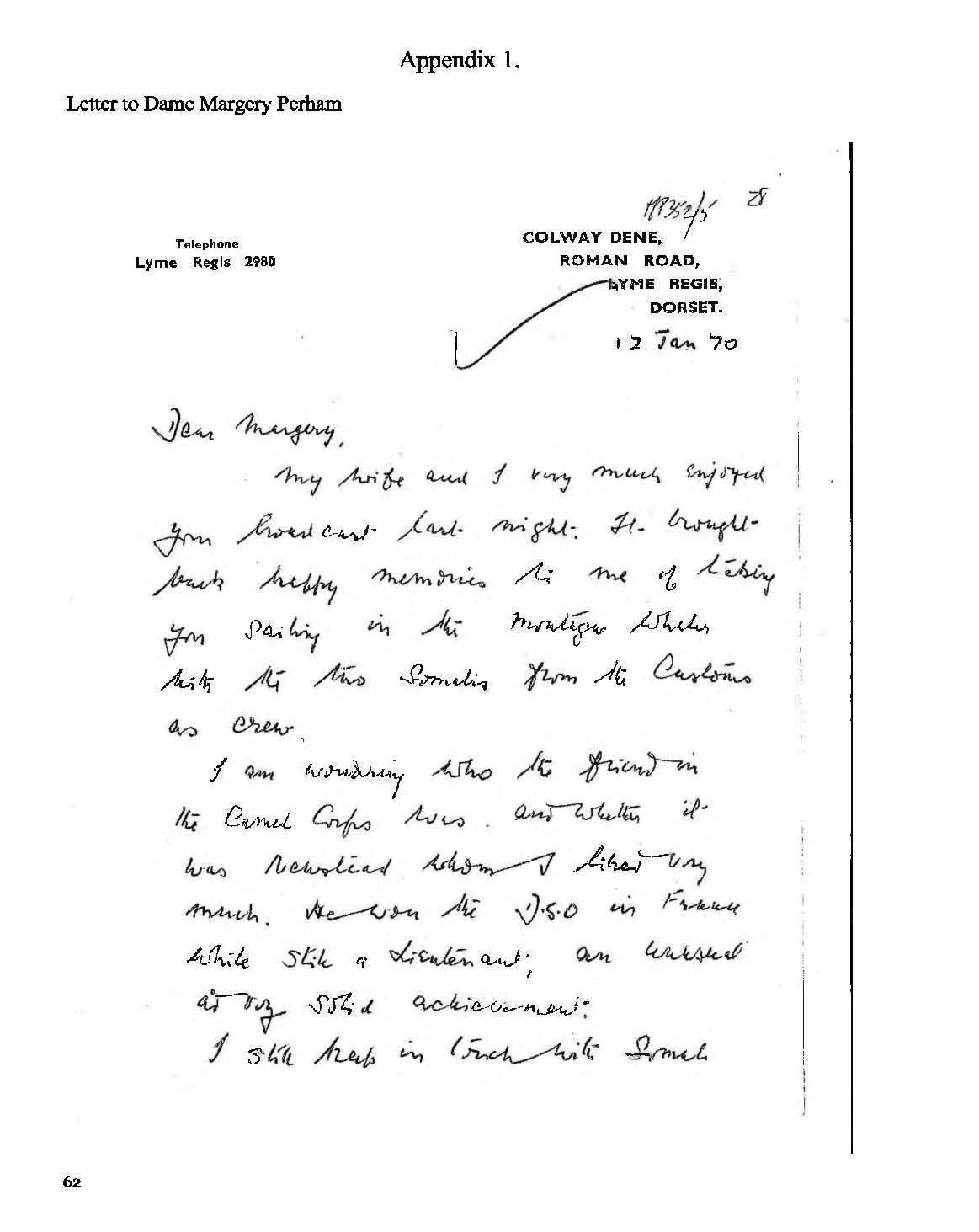

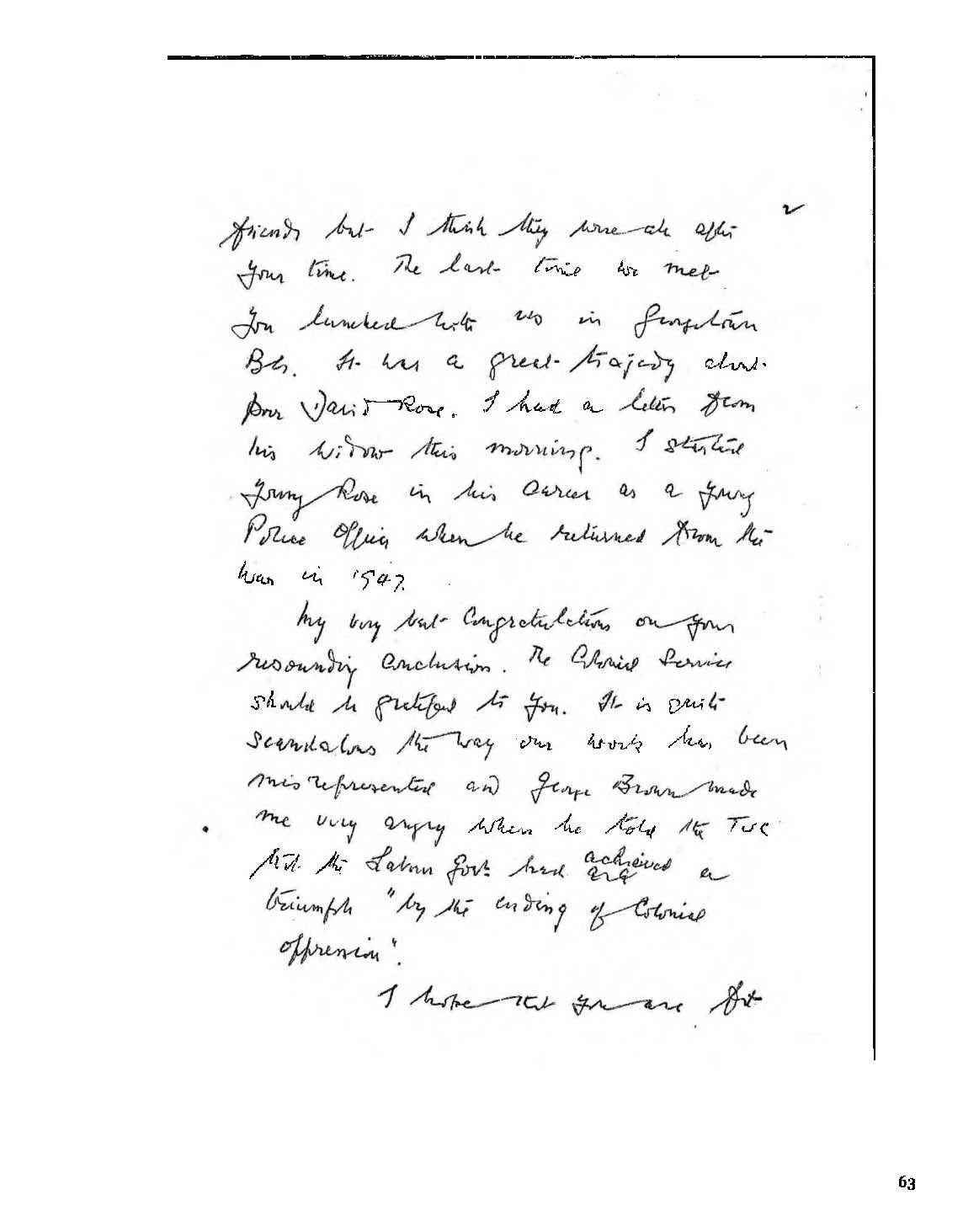

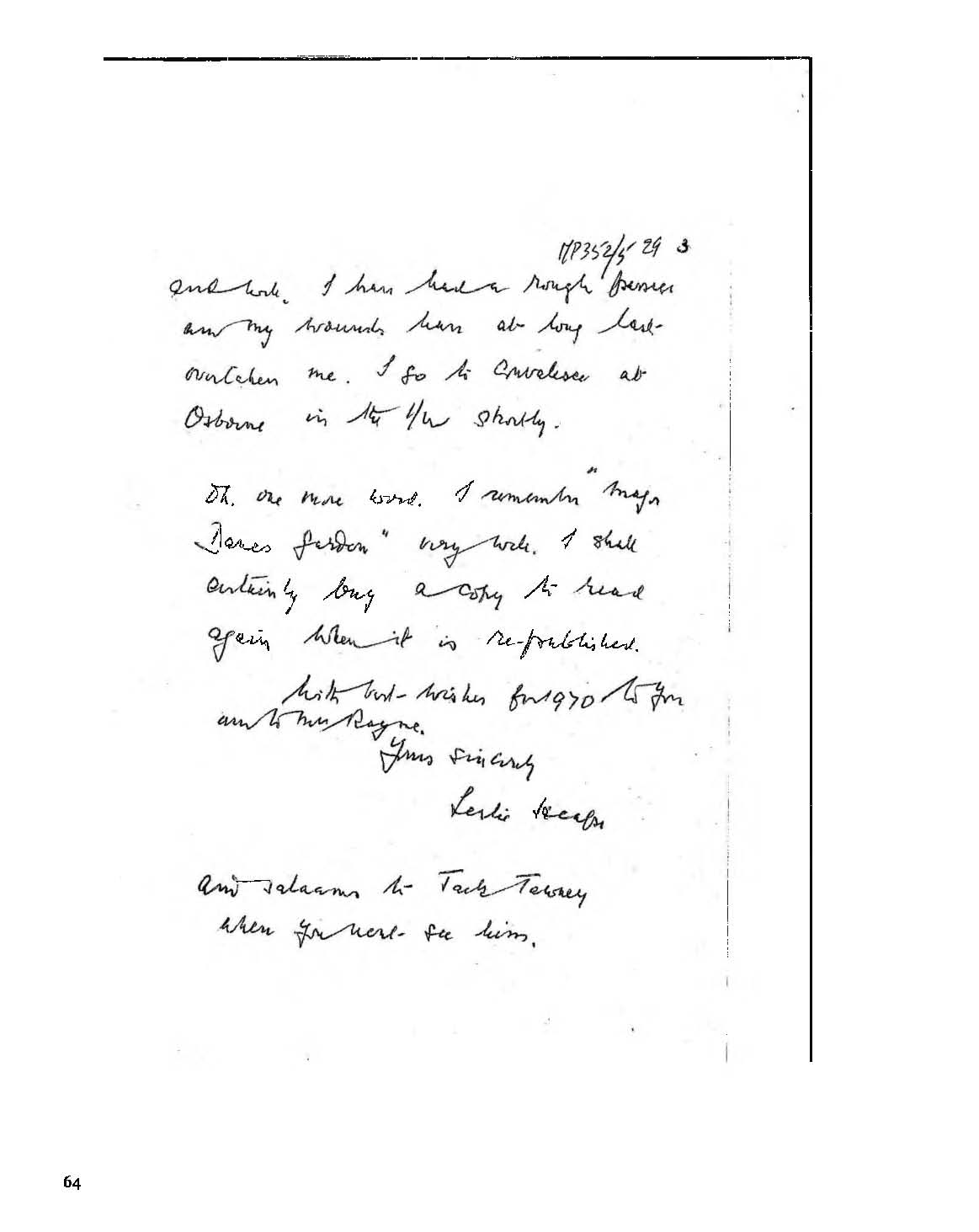

appointed the Director of the Oxford Institute of Commonwealth Studies. Heape wrote to her

in 1970 to congratulate her on her broadcast The Time of my Life which he had listened to

on the radio. He mentioned having happy memories of taking her sailing in Somaliland, (see

letter Appendix 1) Margery Perham was a very important advocate in defence of the Colonial Administration.

While he was stationed in Berbera, Heape enjoyed shooting Sandgrouse at the nearby

waterholes, which he recorded in his Game Book. He particularly enjoyed camping out in the

bush with his Somali servants. He admired the Somalis, who he thought were

splendid people. Writing about the Somaliland Constabulary in Blackwood Magazine, the

author Zeres said this about them. "They are no respecters of persons, and the white man

neither overawes nor embarrasses them. Their manners are charming and their sense of

humour immense. They will treat their officers as racial equals off parade, and the artificial

servility of the Oriental is unknown to them. Further, they will chaff you and argue with you,

but since no disrespect is intended, nobody minds. They are honestly convinced that the

Somali is the finest fellow in the world."

Heape once said that the best Christmas he ever had was the one he spent with his bearer in

the bush in Somaliland. He was reading the novel The Cathedral by Hugh Walpole, which

had just been published in 1922. He had some luxuries from Fortnum & Mason, the famous

London Store, to make his Christmas dinner special. They specialised in supplying what they

called "Joy Parcels" to people serving overseas. He took out twelve boxes of rations from

Fortnum & Mason with him on his tours to Africa, one for each month of the year. The game

he shot added to his diet. He shot a great variety of game, and he brought home several

trophy heads of Antelope, which were displayed in my grandparents' home in Shropshire.

He could never bring himself to shoot an elephant. He had a beautiful Rigby Game Rifle,

which was equipped with a leather case and a brass funnel for pouring boiling water down

the barrel. He said how polluted the water in the bush became in the dry season. The wild

animals urinated round the water holes, which made the water taste foul. This is where

concentrated Camp coffee essences came in handy. The strong taste of chicory masked the

taste of the animals' urine. In 1919, the only practical way to move around the country was

on horseback. Heape rode the same quiet pony for many miles during the ten years he spent

in Somaliland. Riding with a stiff leg cannot have been easy for him, and eventually caused

infection in the bone of his wounded leg.

Approximately sixty miles due south of Berbera, the small government fort of Sheikh

occupied an elevated position on the escarpment. One of his first jobs was to take

charge of a gang of convicts, who were being employed to improve the road from Berbera up

to the fort of Sheikh. This involved constructing a road up the steep escarpment, suitable for

vehicles. He took several photographs of this road, which was little more than a goat track. The convicts broke the rocks by lighting fires round them and then pouring cold

water over the hot stones. It must have taken a long time to reach Sheikh. He was quite

proud of his achievement in improving this important road. Google Earth now shows a

tarmac road snaking up the pass to Sheikh.

Soon after arriving in the colony, Heape witnessed the bombing raids carried out by the

R.A.F. against the Dervishes' fort at Tali. The British had been fighting the Dervishes in

Somaliland for over 20 years. One of the local Sheikhs named Mohammed Abdullah Hassan,

known as the Mad Mullah, had raised an army of 20,000 Dervishes in 1899 to fight the

British, who he thought were destroying his Muslin religion and allowing the Ethiopians to

take over his country. Wars involving Muslins still plague Africa. The Mad Mullah was

finally defeated in 1920 with the help of a squadron of twelve de Havilland DH.9 bombers

from the newly formed Royal Air Force. Heape recalled an incident involving a dead man,

who had to be flown back to Berbera in the DH.9 Air Ambulance. It proved very

difficult to extract the body out of the observer's seat in the aeroplane, when the aircraft

landed at Berbera, because rigor mortis had stiffened the corpse.

The bombing of the Mad

Mullah's fort at Tali was so successful that Lord Trenchard later wrote, "an air force cannot

be built on dreams, but it cannot live without them either, and mine will be realised sooner

than you think." The victory over the Mad Mullah was the first of those dreams that came

true. Control from the air had been born. It would come of age in the 2nd World War. Leo

Amery, the Colonial Under Secretary described it as "the cheapest war in history". The

whole operation cost £77,000, which was far cheaper than transporting a Brigade of troops

over from India and resulted in much lower casualties. It was the first time the RAF had

been used to quell a Colonial rebellion (From Biplane to Spitfire by Anne Baker). Geoffrey

Archer was promoted as Governor of British Somaliland and received his knighthood in 1920

for his part in defeating the Mad Mullah.

Geoffrey Archer was a big man in every sense of the word. Being over six feet

six inches tall, he towered over everyone else. His entry in the Oxford Dictionary of National

Biography gives a description of his long and successful career in the Colonial Service. He

was a keen naturalist and wrote two books, one on the birds of Somaliland and the other

about his personal memoirs. He was extremely knowledgeable about the country and its

people, and his experience in dealing with local tribesmen probably saved Heape's life once

when they were on tour together. During a journey on horseback together, they had to

construct a defensive stockade called a "Zariba" round their campsites each night to protect

themselves from lions and unfriendly tribesmen. Heape woke up one morning to see the

sunlight flashing on a ring of spears belonging to tribesmen, who had surrounded their camp

during the night. The situation could have been serious, had Geoffrey Archer not dealt very

tactfully with the Illaloes.

Various other letters from the Royal Archives at Kew throw light on Heape's life in Somaliland. When he first went out there, he was on secondment from his regiment and was

still technically a regular soldier. The War Office did not officially confirm his transfer to the

Colonial Service until 1921 as the following letter illustrates:

From the War Office

To the Colonial Office

26th September 1921

Sir

With reference to your letter of 6 December 1919, I am directed by Mr Secretary Churchill to

request you to inform the Army Council that he has approved of the confirmation of Lieut. W

L Heape in his appointment as Assistant Secretary, Somaliland after he has completed two

years service from the date of his first arrival in the Protectorate. Mr Heape's confirmation

will accordingly take effect from 4 December 1921.

I am, Sir, Your most obedient servant

H J Read

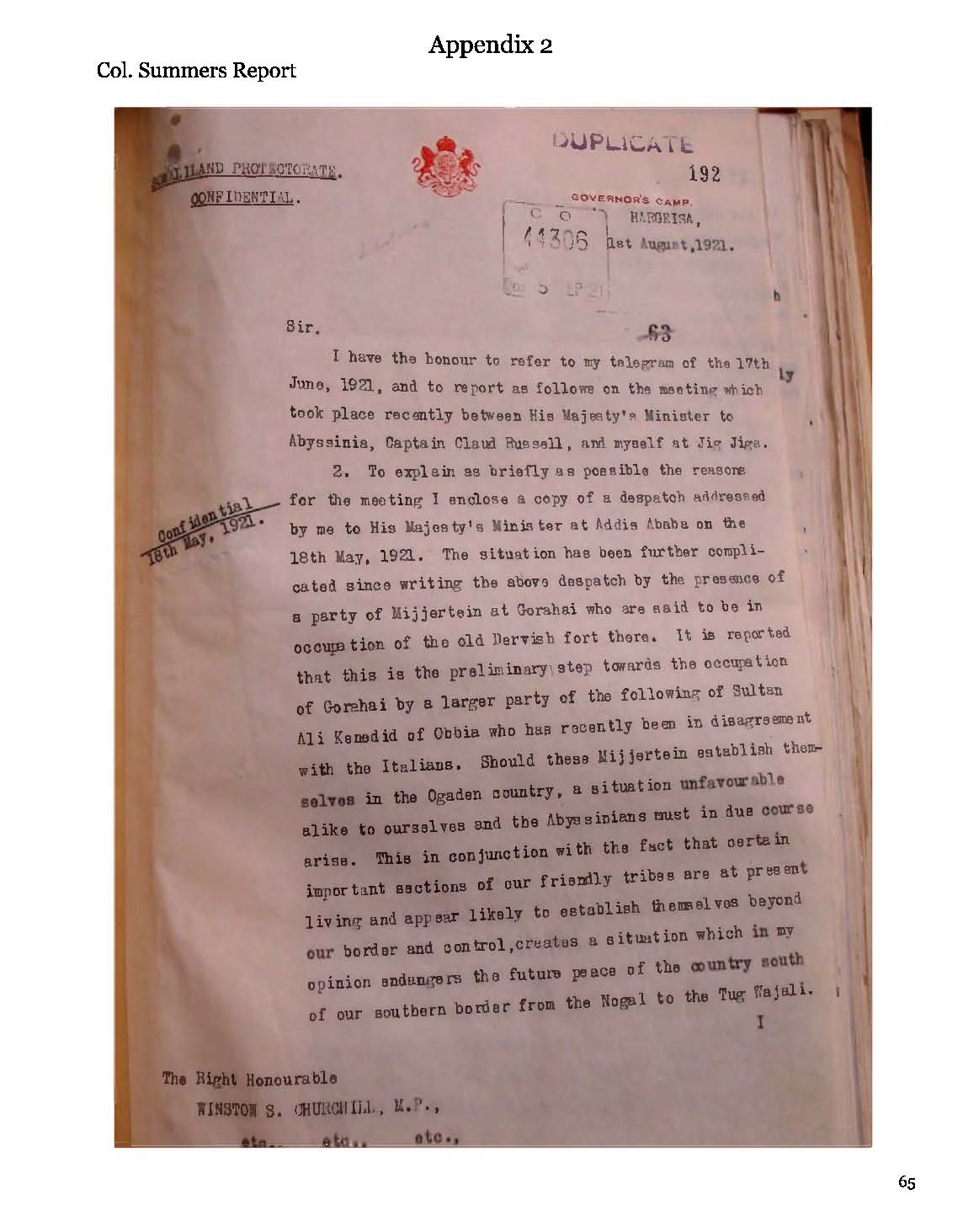

Heape remembered one event in 1921, for the rest of his life. He had to accompany Col. G H

Summers on an official visit to Abyssinia (now Ethiopia). Col. Summers was Acting

Governor of the colony, while Sir Geoffrey Archer was attending the Middle East

Conference in Cairo. The situation in the Ogaden Region of Abyssinia bordering with British

Somaliland had been deteriorating again. The nomadic tribes continued to carry out raids

across the borders. Captain Claude Russell, His Majesty's Minister in Addis Ababa, arranged

for Col Summers to meet the Abyssinian Governor of Harrar Province, Dejazmatch Imaru, at

a place named Jig Jiga about sixty miles across the border. The Governor's party included

Heape from the Secretariat, two officers of the Camel Corps, Major Lousada and Lt. Mackay,

and Major Pack commanding the Police. The party all mounted on horseback, left Gileli in

Somaliland on 16th July accompanied by a troop of the Camel Corps. The meeting with

Dejazmatch Imaru took place on 19th July, and was attended by Captain Russell, Mr

Plowman, the British Consul in Harrar, Colonel Summers and Heape. Capt. Russell opened

the proceedings on behalf of the British Administration. Dejazmatch Imaru gave a long

address expressing the desire of the Abyssinian Government for peace. Col. Summers wrote a

long report about this meeting to Mr Winston Churchill, the Secretary of State for the

colonies, on his return to Hargassia. The full text of Col. Summer's letter to Mr Churchill can

be read in Appendix 2. The Abyssinians feted my Heape, because he was wearing his Army

uniform. They respected him as a wounded warrior, and showered him with gifts, which

Summers made him give back to them. He was only allowed to keep a black silk cape, which

had been given to him by the General of the Abyssinian Cavalry. This cape is still in my

possession.

There is an amusing description of the Cairo Conference in Sir Geoffrey Archer's book

Personal and Historical Memoirs of an East African Administrator. Sir Geoffrey took the

two lion cubs with him to Cairo. They bit Mr Churchill on the knee, and nearly killed a pet

stork belonging to Lord Allenby. There is a picture of all the delegates with Mr Winston

Churchill, which he called "The Forty Thieves and the lion cubs".

The problem of keeping the peace among the nomadic tribesmen, who lived on the borders

between British Somaliland, Italian Somaliland and Abyssinia, did not end with the defeat of

the "Mad Mullah" in 1920. Raids by tribesmen from Italian Somaliland against the tribes in

British territory continued to occur. During the time when the Mad Mullah had been fighting

the British, some of the Dolbahanta people had taken refuge with the Mijjertein tribe in

Italian Somaliland. When the Mullah was defeated in 1920, they returned to British

Somaliland with their livestock. The Mijjertein then carried out raids into British territory to

recover the livestock. In November 1921, the District Commissioner at Burao, Captain A

Gibb DSO met the Italian representatives Colonel Nicoasia and Signor Medici and an

agreement was reached for the Mijjertein to hand over some 1,100 camels, 250 cows, 1,300

sheep, 8 donkies, 3 ponies and 6 rifles by May 1922. The Mijjertein had obviously not

complied with this agreement and the Colonial Office in London became involved. This

incident developed into a "Cause Celebre" between the Royal Italian Government and the

British Government, involving correspondence between Mr Winston Churchill, Lord Curzon

and the British Ambassador in Rome, Sir Richard Graham. The problem led Summers to

seek advice from London.

The following letter written by Heape is part of the Annual Report for Somaliland 1924 held

by the National Archives at Kew.

From: Secretariat British Somaliland

To: The Royal Vice-Consul for Italy in Aden

6th August 1924

Sir

I have the honour to refer to the correspondence ended with your predecessor's letter of 1st

November 1923 and am directed by his Excellency the acting Governor to enquire when Sultan Isman

Mohamoud may be expected to carry out his share of the conditions of settlement agreed at Bundar

Ziaola in May 1922.

I am to add that at the present time many of the Mijjertein, Italian subjects are getting facilities for grazing and watering in the Protectorate and no obstacles have been put in their way. But if the

Sultan will not carry out his promise, a much more stringent control must be exercised, in the hope

that hardship caused to his people will induce in him a more amenable frame of mind.

I have etc

W L Heape

For Secretary to the Administration

His letter is part of a lengthy correspondence between the then Secretary of State for the

Colonies, Mr Winston Churchill, and the Governor of Somaliland concerning an incident in

the Ogaden Region in 1922. Disputes with Italy over the Ogaden culminated in the Abyssinia

Crisis in 1934, when Italy built a fort at Wal Wal 150km inside the border.

Sir Geoffrey Archer had levied a new tax on the tribesmen, which was very unpopular. It was

as a result of this that Captain Gibb was shot dead by tribesmen in February 1922. His career

in the Colonial Service was rather remarkable. Allan Gibb was born in 1877, the son of a

butler in private service in Edinburgh. He had been sent to Somaliland as a Sergeant

Armourer attached to the Kings African Rifles under Colonel Swayne in the first expedition

against the Mad Mullah in 1901. He was mentioned in dispatches for his bravery several

times, and later became a District Officer with the Administration. He was appointed as

District Commissioner at Burao in 1918. On 24th February 1922, Gibb was taking tea with

Geoffrey Archer in Burao, when he was called out to deal with a disturbance by tribesmen,

who were protesting against the new tax. He was shot dead when he confronted the frenzied

mob. He lies buried at Sheikh. His story was recorded in Blackwood Magazine in Tales from the Outposts.

This tragic event was the subject of a parliamentary question to Mr Churchill concerning the

Governor's request for the assistance of two aeroplanes to help in restoring the peace. The

Air Ministry had doubts about sending the aircraft, but two aeroplanes made the risky flight

from Aden to Berbera, and as recorded in Hansard, they were successful in subduing the

rebellious tribesmen. The RAF bombed Burao and a fine of 3000 camels was imposed on the

tribesmen for killing Captain Gibb. This drastic action illustrates the importance given to

maintaining law and order in those days.

Much of Heape's time was spent on dealing with legal problems. One of the more bizarre

problems he was faced with was having to construct a gallows to hang a convicted murderer.

The Home Office sent out instructions on the correct design, which he duly had constructed.

The only problem was that no one could be persuaded to act as hangman for a fellow

Muslim. In the end the murderer had his sentence commuted to life imprisonment and ended

up working in the Governor's garden.

Heape had to return to England in 1926 to be admitted to Roehampton Hospital for a bone

scrape on his wounded leg. Constant riding in Somaliland had caused inflammation of the

bone in his left leg. He was then attached to the Colonial Office in London for a short time

and while there, he joined the Metropolitan Special Constabulary on 9th May 1926 during the

General Strike. He was given a Driver's Permit by the Ministry of Transport and drove a

London bus. The strike lasted 9 days from 4th - 13th May and involved over 1 million workers especially in transport and mining. Heape was able to return to Somaliland later that

year.

He spent almost ten years in British Somaliland, and was eventually transferred to the

Secretariat in Tanganyika in 1929. He travelled via Aden to Dar-es-Salaam aboard the SS

Llandaff Castle in May 1929. (Union Castle Line Passenger List) Tanganyika had belonged

to Germany before the First World War. Britain officially took over the government of what

became known as Tanganyika Territory in 1919 under the terms of the Treaty of Versailles.

A League of Nations Mandate confirmed this in 1922 and after World War Two it became a United

Nations Trust Territory. It was administered by Britain until 1961. Heape was probably

sent there so that he could gain experience in a much larger organisation. The Territory was

governed by a Legislative Council presided over by the Governor and Commander-in-Chief,

Sir Donald Cameron, and an Executive Council consisting of the Chief Secretary, the

Attorney General, the Treasurer, the Director of Medical Services, the Director of Education

and the Director of Native Affairs each with his own department. The Territory was divided

up into 11 Provinces for administrative purposes. The Secretariat, which father joined as an

Assistant Secretary in 1929 was run by the Sir Douglas Jardine, the very same man who had

interviewed him in 1919. Heape was one of seven Assistant Secretaries. In 1930, the

Administration had a staff of 14 Provincial Commissioners, 32 District Officers, 86 Assistant

District Officers and 45 Cadets including one named J Tawney.

Sir Donald Cameron's entry in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography records that he

successfully built up the economy of Tanganyika, improving the harbour facilities and

extending the railway. He established departments of Labour and Native Affairs and

abolished forced labour and manual porterage. He refused to give priority to European

settlement and insisted that the Mandate had stressed the paramountcy of

African interests. He must have been quite a "clean broom," and a bit before his time in

regard to native affairs. Heape enjoyed working under Sir Donald Cameron and Sir Douglas

Jardine as the following letters illustrate:

Secretariat Dar Es Salaam

Tanganyika Territory

10 December 1932

My dear Heape,

May I express to you, on my own behalf and on behalf of all your colleagues in the

Secretariat, our great regret that for medical reasons you are not returning to us.

l can assure you that on personal grounds you will be greatly missed here by us all; but you

will have the satisfaction of knowing that the high standard of care and thoroughness that

characterised your work in the secretariat is daily in evidence, while your zeal in undertaking

and carrying out any duties, official or social, will not readily be forgotten.

I can only add that we all wish you every happiness in the future.

Yours very sincerely

D J Jardine

-------

Government House

Nigeria

16th August 1935

Captain W L Heape served under me for some years in the Administrative Service of

Tanganyika Territory when I was Governor of that Mandated Territory. He served during the

whole of the time in the Secretariat and his work therefore came particularly under my

notice. I can cordially recommend him for Administrative post, for which he may be an

applicant. He is able and industrious and a man of high character; highly respected in Dar-es-

Salaam.

Donald Cameron

Governor of Nigeria

The following letter was written to my mother after my father's death by Jack Tawney, his

colleague in the Secretariat.

January 3rd 1973

Dear Mrs Heape,

I have seen the news of your husband's death with very real sorrow and would like to give

you my sincerest sympathy - a very genuine sympathy indeed, because I had so high a regard

for a man I first met nearly 43 years ago.

When I first went to Tanganyika in 1930 as a raw and brash cadet, I was for a short time

billeted on "Heapie" as he was known to all of us, as to his African "boy" Lemon. I also for

a while shared an office with him in the Secretariat.

At ten years older than myself, with his background as a soldier, who had suffered a great

deal, he was a man to respect, but at once he revealed himself as a splendid guide and friend.

He was a great example to me and to other young men, particularly those of us who were

lucky enough to be taken sailing with him in "Suzanne " and who learnt in addition what a

fund of humour and enjoyment of life he had to share.

Our ways parted - then years later when I edited "Corona" in the Colonial Office in 1950s,

there he was again swinging down Great Smith, as welcoming as ever, and from time to time

we met for lunch.

Then another gap until I came to your house on October 11th 1966. I know he had been hard

hit - I could not have believed I should find such friendliness, such confidence and courage.

My diary records: "I tried him sincerely, he was such a great refreshment and

encouragement to me. It was splendid to find him undaunted. This was a very happy

meeting." I know that many people could have written the same, with real affection.

Yours very sincerely

Jack Tawney

Just as he was making a name for himself in his new posting, disaster in the form of very

serious illness overtook Heape. He stubbed the big toe of his left foot on some coral, while

out swimming. It very quickly turned septic and he was admitted to hospital in Dar-es-Salaam on 25 May 1932. The letter from the Senior Medical Officer in charge of the

European Hospital stated that the superficial lymphatics of the left leg were inflamed and

there was slight general oedema and redness of the leg. On 28th May his temperature rose to

103.4 and he developed symptoms of acute septicaemia. He was injected with anti-streptococcus

serum on 28th, 30th, and 31st of May with apparent benefit. Severe

anaphylactic symptoms developed on 3rd June, accompanied by profuse urticaria. He was

pronounced critically ill. This reaction went on for the next five days. On the evening of

19th June his temperature fell to normal.

In his report, the Senior Medical Officer stated that the inflammatory reaction of a very

severe nature occurred in the seat of old war wounds, and in his opinion it was an open

question whether it would not be better for this limb to be amputated. This was to have

unfortunate consequences for Heape when he was sent back to England.

My father had very nearly died of the heart failure in Tanganyika. He told us the story about

how he called out to his nurse that he was about to die. "No you are not. God does not want

you yet" was her reply. She gave him a teaspoon of Brands Beef Essence, and he recovered.

He kept the Medical Officer's report and the correspondence from Dar-es-Salaam concerning

his illness for the rest of his life. The following letters and telegrams chart the course of his

illness and return to England in 1932:

To Mrs Lutyens (his sister)

From The Under Secretary of State at the Colonial Office

31 May 1932

Madam

I am directed by Secretary Sir Philip Cunliffe-Lister to inform you that he has received a

telegram from the Governor of the Tanganyika Territory reporting that your brother, Mr WL

Heape is seriously ill with septicaemia, but that he is not in any immediate danger.

I am to explain that this news, which Sir Philip Cunliffe-Lister has received with much

regret, has been sent in pursuance of an arrangement by which, when an officer serving in a

Colony is seriously ill, the fact is immediately reported to the Secretary of State for

communication to the relatives.

In accordance with the normal practice, the Governor will at once report any change in your

brother's condition. If no change has taken place in the meantime, a further report may be

expected in about a week. Any reports that may be received will be forwarded to you at once.

I am to add that Mr Heape requested that this information should be communicated to you

rather than to his father, presumably in order that you might exercise your discretion in

passing on the news.

I am. Madam

Your obedient servant

G B Forester

-------

Telegram Received 9th June 1932

Heape has now recovered from acute heart failure. He has high temperature at times.

Condition shows some improvement, but he is still seriously ill. Outlook more hopeful than a

few days ago. His name is off the dangerously ill list.

Governor

The Hospital Dar es Salaam

-------

Dear Mrs Heape

It gives me great pleasure to write and tell you that your son's temperature dropped on the

morning of 13th June and since then he has been better, (the leg is improving)

Of course he is still feeling weak, but we are now hopeful that we shall be able to send him

home sometime in the near future, say in about a month's time; this is unofficial news.

He was very anxious that you should not be anxious about him all the time, but of course "the

Powers that be" had to let you know his condition.

Unless there is another relapse, I shall not write again as he will be writing himself.

I am so pleased and so are we all.

Yours sincerely

Francis M Plant

Matron

-------

To: Mrs Lutyens

From: The Under Secretary of State at the Colonial Office

Madam

With reference to the letter from this department of 18th June, I am directed by Secretary sir

Philip Cunliffe-Lister to inform you that, according to a telegram which has been received

from the Governor of the Tanganyika Territory, Mr W L Heape is leaving for this country by

Union-Castle Mail Steamship Company's steamer "Dunluce Castle" on 5th July. This

steamer is due to arrive at Tilbury on 4th August.

It is assumed that Mr Heape has been granted sick leave following on his recent illness.

I am, Madam

Your obedient servant

He must have been very happy to be going home, but he may not have realised that he would

never be able to return to Africa. When he got back to England, he went to convalesce with

his parents in Shropshire. In due course, he had to go for a further medical at the Colonial

Office in London. He was then told that if he wished to continue to serve in Africa, he would

have to have his wounded left leg amputated. This must have been a very difficult decision

for him. Once again, the terrible wounds he had received in the Great War were changing the

course of his life. He sought advice from Sir Douglas Shields, the eminent Australian surgeon,

who had treated his wounds in 1915. Shields advised him against having his leg amputated,

which proved good advice, because he never had any more trouble with it. But it meant that

he had to give up his chosen career.

He could not return to Africa, but he did not remain unemployed for long. Sir Mark Young

KCMG, the newly appointed Governor of Barbados, offered him an appointment as his

Private Secretary. Heape had to resign from the Colonial Office to take up this new

appointment, but he must have hoped that it would lead to better things. He was well

qualified for his new job having been secretary to the Governor in Somaliland.

Sir Mark Aitchison Young is described in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography as a

sharp minded, intelligent, courageous, far-sighted, energetic, dedicated man, somewhat

austere in character, and very able. Heape got on well with Sir Mark Young, who described

him as an able assistant. They had both served in the Army during the First World War.

During the Second World War, Sir Mark was made Governor of Hong Kong, and was told to

defend the Colony against the Japanese for as long as possible. This he did with the utmost

stubbornness, and unlike Singapore, the Hong Kong garrison, under his leadership, earned in

Churchill's words, the 'Lasting Honour'.

|

|

His Career in the West Indies

|

|

Each Caribbean Island had its own unique character and ethnic mix of people. By the end of

17th century Barbados had become one of the world's largest producers of sugar. The

African slaves, who were brought to work on the sugar plantations, totally changed the

population of the island. In 1698, there were 2,330 white males and 42,000 African slaves, a

ratio of 18 slaves to every white male living in Barbados. In 1933, when Sir Mark Young

was appointed Governor, the white people made up only about 2% of the total population of

the island. Every colony had its own constitution and House of Assembly. The islands were

governed by Great Britain as Crown Colonies with the involvement of the local people

through partly elected Legislative Councils. The Governor controlled the colony on behalf of

the Government of the United Kingdom through an Executive Council.

There are photographs of Heape arriving in Barbados with Sir Mark Young in 1933. He wore a smart white uniform, as Private Secretary to the Governor. They are

pictured together inspecting a Guard of Honour on arrival, and driving to Government House.

He obviously made a success of his new appointment with Sir Mark Young. In 1935, a

position in the administration of the neighbouring island of Grenada became vacant. Sir Mark

must have put forward the name of his Private Secretary for the post. Heape's appointment as

Colonial Secretary and Registrar General of Grenada was published in the Government

Gazette on 15th October 1935. He was paid a salary of £800 per annum and provided with a

furnished house for a rent of £55 per annum. The Barbados Advocate Weekly Newspaper

published a long article on 12th October 1935 about the new appointment of Mr W.L. Heape.

The community of Grenada was very different to Barbados, far smaller and with fewer white

residents. The journalist, Clennell W. Wickham, questioned whether his Barbados experience

would be a handicap, because he would not find any 'exclusive' clubs for white people there

and he would be mixing more closely with the locals.

Grenada was part of the Windward Islands. The Governor, Sir Hugh Popham KCMG, resided

at Government House on the island of St. Lucia. The day-to-day management of Grenada

was left largely in the hands of the Administrator. The duties of the Colonial Secretary were

wide ranging. He acted as Administrator of the island, and was ex-officio Chairman of the

Legislative Council and Finance Committee. He was also Chairman of the Executive Council

in the absence of the Governor. He had to prepare the Annual Estimates for the island, and

these reports written by W.L. Heape are still preserved in Colonial Office Files in the National

Archives. He was responsible for carrying out some of the improvements, which had been

recommended by the Wood Commission. This was probably the most successful and

fulfilling period of his whole career in the Colonial Service. He attended the Coronation of

King George VI at Westminster Abbey on 12th May 1937, and was awarded the King

George VI Coronation Medal in 1937 for his contribution to the community of Grenada.

Leslie Heape married Anice Chandler in London in July 1937. They returned to Grenada

together. I was born in London in June 1938. My mother had returned to London without my

father for the birth of her first child. We both travelled back to Grenada by sea in September

1938. The start of the Second World War in September 1939 meant that we had to remain in

the West Indies for the duration of the war.

Heape was also responsible for the administration of the neighbouring island of St. Vincent

for a short time in 1935, which he undertook with enthusiasm. He kept the following press

cutting about his time on the island of St. Vincent among his papers:

The Acting Administrator

"It is very pleasing to note that during the last two months there has been built up very

cordial relations between Government and the people of this colony. It was on July 12th that

His Honour W.L. Heape arrived from Grenada to assume the appointment of Acting

Administrator of the Colony, and from the very beginning of his term he succeeded in

winning the confidence of all sections. It is true his manners are winsome - a splendid asset

in an Administrator of colonies like these - but winsome ways are not alone sufficient to win

public confidence in St. Vincent, and Mr Heape has been able to bring to play traits of

character that have so favourably impressed all classes that his appointment at any future date

as the substantive Administrator of St. Vincent will be hailed with genuine delight by all the

people.

The members of the Civil Service realise that they must be hard working under Mr Heape;

but the Acting Administrator is himself a very hard worker and there is general conviction

that he is imbued with sincerity and honesty of purpose in his handling of the affairs of the

colony. Mr Heape sets the example of going to the office in time and working till after office

hours. He has travelled in various parts of the colony interesting himself in the question of

land settlement and other matters effecting the social and economic well-being of the people,

sometimes travelling on foot as recently at a visit to Coulls Bay with the object of finding

lands on which to settle a few distressed families.

The details of administration are numerous and the entire task onerous; and we offer our

hearty congratulations to Mr Heape on his succeeding to win, indisputably, the confidence of

this community during his tenure of the acting appointment. He goes back to his substantive

post of Colonial Secretary of Grenada in a few days, but he carries with him the love and

respect of a community genuinely grateful for the unstinted service he has rendered in so

short a time. The Investigator"

In spite of Clennell Wickham's misgivings, Heape got on very well with the local people of

Grenada and St. Vincent. He was well liked by the people of Grenada too. They named a new

house at the Grenada Boys' Secondary School after him, and when he left the island in 1940, an article in the local newspaper praised his deep sense of his public and private

responsibilities and keen desire to serve their country and the Empire. Both my parents

enjoyed the life there.

A far more challenging appointment lay ahead for my father. He was posted to the Bahamas as

Colonial Secretary in May 1940. Sir Charles Dundas was the Governor of the colony at the

time. Sir Charles had been a popular administrator in Tanganyika in the 1930s and they

probably knew each other.

The Bahamas has had a long and chequered history ever since Columbus first made landfall

on the island of San Salvador in 1492. It was not an easy Colony to govern, because of its

constitution. The House of Assembly, made up of twenty-nine members elected by the white

business community on New Providence, had very wide powers under the constitution. They

did everything in their power to protect their dominance over the mainly black population of

the colony. They ensured that practically all economic activities benefited New Providence and

that the outer islands, where most of the black population lived, were left undeveloped. The

Governor had the difficult task of keeping the House of Assembly in check through his

Executive Council, on which Heape served as the Colonial Secretary. Although the Governor

had a right of veto over any proposed legislation, it was never easy for him to persuade the

House of Assembly to carry out the wishes of the Colonial Office in London. In other words,

the life of the Governor was no sinecure, and it was not a popular posting.

It was as a direct consequence of the war that Duke of Windsor was suddenly appointed

Governor of the Bahamas. Sir Charles Dundas was posted to Nigeria, leaving Heape as the

Acting Governor of the Colony. The Duke and Duchess of Windsor arrived on 17th August

1940. It was Heape's responsibility to organise their reception and welcome them to the

Island. There are pictures of him with Duke and Duchess arriving in Nassau Harbour. Heape is also shown standing behind His Royal Highness the Duke of Windsor as

he was being sworn in as Governor by the chief Justice, Sir Oscar Daly.

My mother was also a member of the welcoming party for the Duke and Duchess that day. The

local New-Herald Newspaper reported that Mrs W L Heape, wife of the Acting Governor, set the

fashion by bowing to the woman for whom the Duke had given up the throne. Other officials then

followed her precedent. The Duchess had not been awarded the title of Her Royal Highness, and the

Palace had stipulated that women should therefore not curtsy to her.

As Colonial Secretary, Heape had to work very closely with the Duke of Windsor for four years. It

was to prove a period of re-adjustment for them both. The Duke referred to the Bahamas as a third

class British colony. He was very unhappy about being sent there. He was unfamiliar with Colonial

Office procedures, and Heape had never had any dealings with Royalty. In a letter to the Secretary

of State for the Colonies, the Duke admitted that he came to the Colony without previous Colonial

Administrative experience and completely green to Colonial Office routine work. He said that

Heape had been of the greatest assistance in putting him wise over many things concerning

procedure in the Colonial Service. Their teamwork had been good, because he had been glad to

learn from Heape, and he had been able to teach him things, which Heape would find useful in his

future career.

As Colonial Secretary, Heape had to act as Governor of the colony whenever the Duke was

absent. The Duke was on holiday in Canada in October 1941 when a hurricane hit

the Bahamas. Winds of 102 mph were recorded in Nassau, killing three people and

causing considerable damage to property. The local paper 'The Argus' reported that

the streets of Nassau were strewn with debris including wreckage of boats from the

harbour. The Colonial Secretary was thanked for the prompt and effective

measures he took to obtain first hand knowledge of the people's needs, and for

sending relief to the stricken out islands. The Duke was away from the colony on

four occasions during 1940 to 1942. Heape also had to sign his name as Colonial

Secretary on the banknotes. A rare 4/- Bahamas Banknote bearing the signature

W.L. Heape sold for $748 on the Baltimore Auction in 2012.

As well as the clique of local white businessmen, known as the "Bay Street Boys", there were

a number of other rich businessmen living in the colony, attracted there because Income Tax

was not levied in the Bahamas. One man in particular was the Swedish Industrialist Alex

Wenner-Gren, who owned an estate named Shangri-La on Hog Island and the largest private

yacht in the world called the 'Southern Cross'. Among his many business activities, Wenner-Gren had interests in the Swedish armaments manufacturers Bofors and Saab, and he was

purported to have had dealings with the Nazis before the war. The other immensely rich man

living in the Bahamas at that time was Sir Harry Oakes, who had made his fortune in gold

mining in Canada. He had moved to the Bahamas and taken British citizenship in 1935. He

had been created a Baronet for his philanthropic work in Britain and the Bahamas, where he

was a dynamic investor in property. He had stimulated the local economy by developing the

Oakes Field Airport and the British Colonial Hotel in Nassau as well as the Golf Course and

Country Club. He was the colony's wealthiest and most powerful resident in 1940. One of the

local businessmen, who had close dealings with Sir Harry Oakes, was the property developer

and speculator Harold Christie, who had made a fortune during the Prohibition era in America.

Sir Harry owned various properties on New Providence including a holiday house called

Westbourne, which he leased to the Duke and Duchess of Windsor while Government House

was being made ready for them. The Duke and Duchess socialised with both Alex Wenner-Gren and Sir Harry Oakes. It was after attending a cocktail party given for the Duke and

Duchess on board Alex Wenner-Gren's yacht that my father came home very depressed

about the progress of the war. Wenner-Gren was openly saying that Germany was bound to

win and that the Allies did not have a hope. My father suffered a sleepless night, because he

felt that the Swede knew what he was talking about. My mother was more philosophical. She

said, "Right will triumph in the end" and her instincts were proved correct.

W L Heape was made a Companion of the Order of St. Michael and St. George in 1942 for

his services to the Empire. Two other events in June 1942 were to prove very significant for

both my parents. There was a very serious civil disturbance in Nassau on 1st - 2nd June and

my sister was born there on 4th June. The riot by large numbers of the black population was

because of a dispute over the wages being paid to the local labourers working on the site of

two new airfields on the island. The US Government was responsible for constructing these

airfields, as part of the War Effort. Work on the Project had started on 20th May. The local

unskilled labour force was paid at the local rate of 4/- a day, which was far lower than the

wages being paid to the American employees working on the site. The Bahamas did not have

any Trades Union legislation, and there was no formal way of settling a major labour dispute.

The Duke and Duchess of Windsor sailed to America aboard their yacht "Gemini" on 28th

May and left my father in charge as the Acting Governor. On 29th May a letter demanding an increase in wages was received at Government House from the local labourers. Heape

responded by agreeing to set up an Advisory Committee to look into the matter as soon as

possible.

At 4pm on Sunday 31st May a large crowd of workmen gathered outside the Contractors

Offices and were informed that their complaint would be dealt with as soon as possible. The

crowd had started to leave, but a younger element stayed on. Captain Sears, the second in

command of the Bahamas Police, with four constables tried to arrest their leader, a man

named Green. The crowd surrounded the policemen and Captain Sears drew his revolver. The

crowd then dispersed and it was agreed that work should be resumed on Monday morning.

However, at 7.30 am on Monday morning the General Manager of the Project informed the

Authorities that the men were refusing to work. The forces of Law and Order available to the

Government were very small. They consisted of a Police Force totalling 150 policemen

commanded by Lt. Col. R Erskine-Lindop, and a company of the Cameron Highlanders made

up of 5 officers and 130 men commanded by Col. A. Haig. There was also a Bahamas

Volunteer Defence Force of 146 members under Capt. W. D'Arcy Rutherford. The Police

had no modern equipment such as tear gas for controlling crowds.

Heape, acting as the Governor, instructed Col. Erskine-Lindop to send a force of policemen

to the Main Field to report on what was happening. Capt. Sears and four policemen went to

the scene and reported that the crowd of striking labourers were heading into town. The

crowd were armed with machetes and sticks, and were obviously intent on causing trouble.

Heape then instructed the Commissioner of Police to send a force of Police and Army to

prevent the crowd from coming into town, but the Commissioner decided to keep his men at

the Police Barracks until it could be ascertained which route the crowd would take. Heape

also instructed him to contact Colonel Haig at once and consult him about controlling the

crowd.

At 9 am. Col. Erskine-Lindop turned out his men at the Police Barracks and personally

ordered them to load their rifles. He also requested assistance from the Military and Col. Haig

ordered a platoon of Cameron Highlanders to go to the Police Barracks. The crowd by that

time had started to damage some cars. The Commissioner also called out the Stipendiary

Magistrate, Mr F. Field. The Police then proceeded to the Central Police Station in the Public

Square at the south end of Bay Street. The Attorney General, Mr E. Hallinan, then addressed

the crowd from the steps of the Colonial Secretary's Office. He told them that the American

Authorities had thought it might be necessary to bring in their own labour force to work on

the Project, but the local workers had done so well that it had not been necessary and he

appealed to the crowd not to spoil the good impression they had made. His words did not

have the desired effect on the crowd, who were then asked by Col. Erskine-Lindop and Capt.

Sears to leave quietly and some of them threw down their sticks in a heap. Although the

Police remained in square, some of the crowd then started breaking shop windows in Bay Street. At about 0945, Col Erskine-Lindop led his men down Bay Street, where the

crowd attacked them and he was struck in the face by a bottle. The crowd ran into the side

streets and alleyways and started to pillage the shops. At 1015, Heape requested

assistance from the military, and Col. Haig ordered a platoon of soldiers to proceed to the

scene. They were told not to fire unless absolutely necessary and they unloaded their rifles

before joining the police. The police had only fired two shots up to this point. By about 1100

Bay Street west of Rawson Square was quiet.

But that was not the end of the rioting. Shortly before noon, trouble broke out again in Grant's Town, and the crowd started breaking into bars and looting. A large angry crowd had

gathered at the Cotton Tree Inn, and it was decided that the Riot Act should be read. A

Company of the Cameron Highlanders accompanied by the Commissioner of Police and the

local Magistrate proceeded to the scene in order to read the Riot Act, and was immediately

stoned by the mob. One of the soldiers was badly injured. At some point, the police opened

fire and two rioters were killed. The crowd became very hostile and started to attack the local

Police Station. The three constables in the Police Station managed to escape, but the Police

were subsequently criticised for abandoning Grant's Town. By this time the crowd were very

drunk on the liquor that had been looted from the local bars. Trouble broke out again on

Tuesday 2nd June, and two more local shops were looted. Heape, acting as the Governor,

imposed a curfew. The curfew was still in force on 4th June, when The Duke of Windsor

returned to the Colony, but the rioting had stopped and the men had started to go back to

work on the Project. The Duke revoked the curfew on 8th June and made a broadcast on 30th

June, addressing some of the grievances expressed by the workers. But that was not the end

of the matter.

The white businessmen of Bay Street were determined to blame the Government for failing

to prevent their properties from being damaged by the rioters, and the members of the House

of Assembly appointed a Select Committee to look into how the Authorities had dealt with

the riot. In particular, they blamed Heape, as the Acting Governor, Eric Hallinan, the

Attorney General and Col. Erskine-Lindop for the way they had handled the disturbance. The

Select Committee had the power to call officials to give evidence before them. They

demanded that the three Government Officials should be summonsed to appear before the

House to account for their actions. This would have had very serious consequences. The

Duke sent an urgent cable to the Secretary of State in London asking for advice.

Mr Beckett, at the Colonial Office, stated that unlike Southern Rhodesia and Ceylon, the

Bahamas had no written laws about the powers and privileges of the House of Assembly. The

House had been in existence for 200 years and in 1817, they had imprisoned the Attorney

General for misrepresenting them in connection with the Abolition of Slavery. The last time

anyone had been brought before the House was in 1845, when the Editor of the Nassau

Guardian had been summoned for misrepresenting the proceedings of the House. Questions about the Riot had also been tabled in the House of Commons and the Secretary of State For

the Colonies, Sir Oliver Stanley, had been informed. The Prime Minister Winston Churchill

was also consulted. Mr Beckett advised The Duke of Windsor against his proposal to refuse

to allow his Officials to appear before the House of Assembly. London suggested instead

that he should send the Colonial Secretary to wait upon the Speaker of the House, and explain

the position fully to him, pointing out that the Government intended to hold a full and

impartial enquiry headed by a retired Colonial Judge. They emphasised the impropriety of

having a constitutional row between the House and the Governor at such a time, and

suggested using courtesy and tact to smooth matters over. Heape must have been successful,

because the House of Assembly accepted the appointment of Sir Alison Russell KC to

conduct a Commission of Enquiry set up by the Governor. Two local Bahamian residents, Mr

Herbert McKinney and Mr Herbert Brown were also appointed to sit on the Commission to

represent local interests.

It had been a serious civil disturbance. Eight people had been killed and forty-six wounded.

There had been considerable damage to property, and although the rioters had refrained from

attacking civilians, it was feared that social wounds had been created, which would not be

forgiven or forgotten. There were deep-lying causes of discontent among the poorer

labouring classes, which had to be addressed. This involved persuading the House of