|

Introduction

|

|

In the following pages I relate the story of four years between September

1956 when I went up to Oxford and August 1960 when I completed

my first tour as a District Officer in the Colonial Service in Tanganyika

(renamed Tanzania in 1964).

In introducing the first part of these Memoirs I offered apologies for writing

so much about my school and university life. My only excuse was that I enjoyed

doing so. In this part of the Memoirs I have a different reason for recording so

much detail.

As a District Officer, I was a junior administrator and something of a jack of

all trades while being an agent of the colonial power when Tanganyika was a part

of the British Empire. It was a job in which I was very happy and totally fulfilled

and I hope family readers will find it of interest to learn what I was doing then.

At the same time I know that the type of work I did has subsequently been

subject to heavy criticism. In the early 1960s, historians at the University of Dar

es Salaam charged the colonial government with incompetence and at times a

malign intent, and succeeding historians and journalists have either ignored

its achievements or sought to disparage them. For example, the President of

the Republic of Tanzania said not long ago, “The colonial government had no

intention of developing the country but just wanted to exploit its resources.” His

views appear to be shared by some commentators in this country, and even by

authoritative voices in places like the BBC and the Times newspaper.

These criticisms sadden me. Our colonial administration deserves to be

given a fair hearing, and our work to be assessed even-handedly. For this reason,

should these pages ever reach a wider readership beyond the family, I have put

on the record some detail of my work and leisure to enable readers to judge

for themselves. I have tried to avoid hindsight and those loose generalisations

that hide reality, nor have I relied on my memory which is rose-tinted and

wholly unreliable after sixty years. Instead, I have recorded wherever possible

the words written in my diaries and weekly letters home about my daily life

and my thoughts about it at the time. If this detail is found to be tedious, I

ask forgiveness for the attempt to give a faithful account of the life of a young

District Officer in a colony aspiring to independence.

Please do not assume I am proud of all my actions here recorded. I may

sometimes appear elitist, paternalist and patronising. Some of my behaviour

in those far off days may even seem distasteful and racist to readers. If they

are crimes, I plead guilty, but that was the way we were. Our moral standards

are constantly changing; and today’s readers are likely to view certain types of

behaviour quite differently to the way we saw them all those years ago. Morality

evolves progressively and will continue to evolve; and I have no doubt that some

of the things we do and say now will be considered unsavoury and repugnant

fifty years hence.

There is a short bibliography at the back of this Memoir. Many of my

contemporaries and predecessors have published books about colonial

Tanganyika. I have recently re-read a handful of them in order to refresh my

memory of the people, places and events of those days, and I gladly acknowledge

my debt to these authors. I would also like to express my grateful thanks to

Lawrence Charlesson for his expert and extensive help in drawing the maps of

the Districts in which I served at the back of the book. I wish to record too my

appreciation of the help of Alison Little and my wife Joan in putting together

the index of this book.

A glossary of acronyms and Swahili words that we used every day in our

work is also appended in the sidebar. Four words were so frequently employed in

Tanganyika at that time that I have anglicized them. They were: ‘safari’ meaning

journey, ‘boma’ meaning the District Office, a fortress, or even a cattle stockade,

‘baraza’ meaning a court house, meeting or council, and ‘shauri’ meaning

complaint, problem or affair.

As to the names of the Tanganyikan tribes, correct Swahili would require the

use of prefixes to indicate whether the reference is to one member of the tribe or

many members, to their land or to their language. I ask forgiveness of the purists

for omitting all such prefixes in order to simplify the text.

Dick Eberlie

Tavistock, May 2014.

|

|

Chapter 1: Joining the Colonial Service

|

“What’s become of Waring

Since he gave us all the slip,

Chose land-travel or seafaring,

Boots and chest or staff and scrip,

Rather than pace up and down

Any longer London town?”

From “Waring” by Robert Browning.

Making up my Mind

My father used to invite me from time to time when I was on holiday at

home to drive him in his Vauxhall on his afternoon visits to patients around the

town. This was useful to him and interesting to me as we were able to chat and

get to know each other a little while I was taking him to the home of the next

sick family. On one such drive during August 1953, soon after I returned home

from Hong Kong, we sat for a few minutes together outside a patient’s house on

the Kingsbourne Road and he remarked with surprising emphasis,

“I can remember before I went to university wanting to do

something - wanting to heal men with my hands, to make them well.

Do you have a similar feeling?“

“Well”, I answered, “I think I know. I want to lead men, to help

them that way. I want to be able to advise them, train their minds and

make the best of themselves.”

My father was directing me to think seriously about my future career. I felt

strongly at that time, just back from an exciting life with the Regiment, that the

army was my first choice. I had found a great stimulus in leadership, training,

directing and organising young men and in helping to shape their characters in a

positive way. I was convinced that this was the life for me. I had a deep affection

for the young soldiers who had been in my charge. I mentioned the Regiment in my prayers, re-read each night sections of the diary I had kept in my Hong

Kong days, and despaired that I could ever regain the particular happiness I had

felt among my soldiers. I wrote one day in my diary - rather pretentiously - an

extract from a Herbert Read war poem.

“O beautiful men, O men that I have loved,

O whither have you gone, my company?”

In those lazy weeks before I went up to Cambridge, I was, however, just

beginning to turn other options over in my mind. I said to myself the colonies

would provide me the same opportunities for fulfilment as a leader and shaper

of men, but the future of the world did not lie in Africa or the Pacific Islands

where the colonies lay. I wrote in my diary:

“Reading leaflet about the Colonial Service. I don’t want to do

that sort of a job; stuck miles away from England - the country that

matters. Who cares about the Africans? Besides it means another year

up at university reading anthropology and such muck. I want to get

out now and start doing something for somebody. Let other people

stagnate if they like.”

To my mind at that time, I could have the greatest influence for the good

among young men like the Londoners whom I had grown to know when I was

training Royal Fusiliers. At the same time I was eager to go abroad again for the

stimulus of seeing new sights and living among different peoples. I was torn

between a wish to help young men make the most of their lives and an eager

desire to travel.

Graeme Sorley, with whom I shared rooms at St John’s asked me, early in

our friendship, what I wanted to do. I replied I did not want to be ‘tied down’

in a business; I thought the Foreign Service was not a job where one could

do much good; one had to be a ‘social person’ and I was not; and one had to

be interested in international affairs which I was not. I told him I should like

to ‘serve’ the young uneducated men such as those I had worked with in the

Army, that is to train their characters and exert some positive influence over

their natures. I explained I should like to do this sort of work somewhere like

London, or possibly still in the Army; but I also insisted I wanted to go abroad

again. I thought the Colonial Service offered the best alternative, but I was

not then enamoured of the idea of working with Africans. Graeme was a good

listener and patient in teasing out my answers to his questions. I was incoherent

and contradicted myself often enough, but the conversation helped me clear

my mind and work through my own ideas. He let me talk the night away and it was very good for me. Oddly enough, I never remember asking him the same

question.

John Streeter, an OS and a retired judge, ran a boys’ club with the school’s

support called ‘Sherborne House’ in Union Street in Southwark, and I had met

him several times when he had brought a group of boys down for a weekend

at Sherborne while I was at school. On a couple of occasions I had joined the

party, going out with the boys on trips to Weymouth or swimming in Lulworth

Cove. So I made a point during my first Christmas vac of passing some time

at their London club house to see if I could be of use to them, and if I could

find satisfaction in helping the young men from South London who spent their

evenings there. I gave some thought to the possibility of working in that sort of

environment, but it would have meant living close by, which seemed to me to

be neither possible nor desirable.

In September 1955 I went back to my old prep school at Swanbourne House

in Buckinghamshire to teach history to the junior boys. It was an opportunity

to find out if I liked teaching - while at the same time catching up with some

reading required for the Tripos. I enjoyed standing up in front of the children

and telling them about the Battle of Trafalgar - how Nelson split the French

line and destroyed the enemy ships at the cost of his own life - for it was good

dramatic stuff - but I did not seem to fit into the staff room where the teaching

staff gathered in between lessons, and I thoroughly disliked the evenings. I had a

room in a pub in the village and had no choice but to sit in the bar and drink the

beer. I was persuaded to try the super-strong ale called something like ‘Dragon’s

Blood’. I was drunk on a pint of the stuff. Frequently I went to bed with a thick

head and woke up the following morning with a headache. Perhaps I was being

unfair to the school, but I decided that was not the way I wanted to live.

In my first term at John’s, I attended a talk at the Colonial Service Club in

Cambridge. I met a number of serving officers who I thought were decent chaps

and contented in their work; but at the end of that visit I was still not persuaded

that the Colonial Service was the life for me. I still thought I should prefer to

work with men of my own country. I was to ponder the options from every

angle day in day out over the next two years while I slowly made up my mind.

Cambridge University had a Careers Advisory Service in a big Victorian

house on the Trumpington Road where I sought advice and spent some time

in my second year. I picked up a lot of pamphlets and skimmed through them,

as one does, and I had two interesting interviews with Careers Advisors. They

helped me to see how the army would offer only limited satisfaction. They told me about local government service but it appeared then to offer little scope.

They showed that there were jobs in the Civil Service that offered great rewards

but they were few and far between. They explained that the Diplomatic Service

provided huge rewards but was very difficult to enter. On the other hand they

told me the Colonial Service offered satisfaction of a different sort and was not

nearly so difficult to join.

Part of the problem was that I found it difficult to envisage what the life of

a colonial administrative officer would be like. I had read Edgar Wallace’s books

about “Sanders of the River”, seen the 1930s films, and thrilled to the romance

and excitement of the life of Bones, the lanky young district officer and hero

of the stories. I had enjoyed “A Pattern of the Islands” by Arthur Grimble that

Margaret had given me for my twenty-first birthday and been fascinated by the

delightfully-written tales of colonial administration in the South Sea Islands. I

tried to use my imagination but gained little idea what I should be doing and

how I should live in that sort of work abroad. It was somewhat frustrating,

but then again the mystery and uncertainty were part of the attraction. One of

my main motivations was the search for adventure and the rich excitement of

travelling in a new and strange world. I wrote in a questionnaire forty years later

about my reasons for applying for a job in East Africa, and added,

“I had little idea of what lay ahead, but that never worried me. It

merely added to the thrill of the new life before me”.

With the help of the Careers Service and under the influence of Robbie

Robinson’s teaching about the “Expansion of Europe” I came to realise that

there would indeed be a useful job of work to do among a colonial people, and

it would be immensely interesting to do so. I was clear I would be asked to

carry considerable responsibility from the start, and I eagerly looked forward to

a job in which I could have a real and positive influence over people from the

beginning. However I did not want to go too far away from home, and I did not

consider seriously either the Far East or the Pacific Islands. My attention slowly

focussed on East Africa because I thought (however mistakenly) that the natural

wealth of the colonies of West Africa would rapidly enable them to look after

themselves. Finally I plumbed for Tanganyika as the poorest and least developed

of all the African colonies. Life, I judged, was likely to be most exciting there,

while the need for help, guidance and leadership from people like myself was

likely to be the greatest.

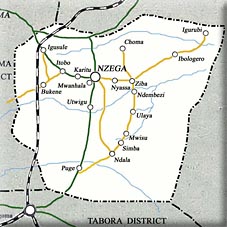

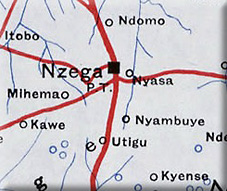

Hindsight

Two years later, having learned my job and enjoying it enormously, I

rationalised my choice of career and country in which to serve in the following

note to my parents from Nzega where I was then stationed - using a medical

metaphor which I thought would interest my father:

“Me, I am present at the birth of a nation; but it’s not a simple

birth - a very big baby, rather a strong one, and we’re going to have

to be careful to prevent a miscarriage. After all, Tanganyika is only

another in a long line of babies of the Mother Country. If the United

States came forth in 1780 by a Caesarean, the line starts in 1840

with Canada, and continued in the 1850s with Australia and New

Zealand, in the 80s with Boer South Africa, in the 1920s for Southern

Rhodesia and Ceylon, and so on. Granting independence when the

colony is ready for it is not a new policy. It’s over a hundred years old,

and it’s never done the Mother Country any harm. If she wants to

control a country, she has always done it cheapest by trade and finance,

as she did and still does in South America, Turkey etc, as we used to

in Egypt, China etc. A colony is a huge drain of cash and troops (as

in Kenya over Mau Mau time, or as in Cyprus) - which the Mother

Country can ill afford when she has to pay millions to placate railways

strikers, to keep an army in Germany, and still to keep a reserve in case

of a real emergency…

Financially and strategically, it couldn’t matter less if Britain

were in Tanganyika or not. This country has no decent port and no

worthwhile export. Sisal has been their biggest thing in the past,

but is negligible now. We also produce a little coffee which South

America produces much better, a little cotton of lower grade than that

in Southern USA, a few peanuts, cashew nuts, tobacco, diamonds

which have profited one man only - Williamson, gold which is now

exhausted, and coal when the railway gets to that area in twenty years’

time. There’s nothing in Tanganyika worth taking but hundreds and

hundreds of miles of hot bare bush.

I’ve told you a little of our sporadic strikes; in fact they have

occurred all over the Western Province in the bigger centres of labour.

Each strike has been very minor, and in each case the police have

arrived in good time to see fair play. In a few years, the labourers’

unions will be properly organised and all over the Province they will down tools together and riot in six places at once. The Police have

only one mobile squad in the whole Western Province to cover several

thousands of square miles. Somewhere the Police cannot get to, there

will be shooting and a local war will start. There is one battalion of

King’s African Rifles in the country, but they are tied to the real trouble

spot, Dar es Salaam. So even for a local Nzega war, we should have

to ask for troops from the UK. However it’s still a few years off, and if

meanwhile our District Council can win everyone’s confidence, such a

day of horror will never come.”

So it was, that in the winter of 1955, feeling my way to this position, I made

up my mind. With the support of my college on the one hand and my parents

on the other, I wrote to the Colonial Office making formal application to join

the Colonial Service. There was no written entry examination; candidates were

selected for recruitment on their record and personal interviews. On receipt of

my application, the Recruitment Branch of the Colonial Office wrote to my

three nominated referees - from school, the army and my college - and called

me for interview. On two occasions early in 1956, I went down to Sanctuary

Buildings in Great Smith Street, not far from Westminster Abbey. The offices

were dark and ugly (later converted into the Westminster Public Library); there

was not much of a reception and no welcome, and I was sent down bare and

dreary corridors for my interviews in cold, featureless meeting rooms.

First I was seen by the recruitment staff, and next I was put at the end of

a long table facing half a dozen senior men. I have no recollection of their

questions or my answers, but I must have satisfied them and my references must

have been adequate. A letter dated 8th March 1956 reached me at St John’s

approving my probationary appointment to the administrative branch of the

Overseas Civil Service - as it had just been renamed - and selecting me to go to

Tanganyika, as I had requested. There were just three conditions. I must secure a

satisfactory degree, pass a medical examination, and obtain a satisfactory report

after an Overseas Service Course at Oxford University running for one academic

year from 8th October 1956.

Oxford

What was I doing in Oxford after three years at Cambridge? I could have

attended the Course in Cambridge where I knew the Colonial Service Club

in Petty Curry and Mr McCleery who ran it. I had liked his set-up, but all

my Cambridge contemporaries were dispersing, and I hated the thought of returning to St John’s as a graduate, living in digs in the town on my own, and

knowing very few people. In addition I thought it right to take this opportunity

to see how the other half lived; so I concluded I should ask to go to ‘the other

place’ - and my request was granted. I applied to be accepted by Balliol College,

St John’s sister college in Oxford; and the Master agreed to have me for the

Academic Year 1956/57.

I was required to report to the Colonial Service Club at 3 South Parks Road,

in Oxford several days before the undergraduates arrived to start their new term.

Our timetable was run quite separately from theirs, and the Club was to be the

focus and meeting place of the thirty or so of us probationers on the Course.

It was conveniently located next door to Rhodes House where we were able to

study the extensive archive of commonwealth and colonial papers.

Mr Murray ran the Club in a genial and friendly way and was our Course

Supervisor. He had been an administrative officer in Nigeria and knew the

ropes. There was a bar, a dining room, a common room, library and some

bedrooms for visiting colonial officers; it was the probationers’ base for both

study and leisure. There were lectures of general interest and periodic ‘Club

Nights’ when we watched films or simply chatted about our studies and this and

that. It was thus at the Club that I met the others who were on their way with

me to becoming colonial administrative officers.

Many of them were Oxford men who had gained their degrees there and

chosen to stay for their fourth year, but several had joined us from northern and

Scottish universities, and a few had already been doing the job in a colony and

returned to improve their knowledge. We were a good mixed bag; and between

us we had been allocated to just about all the then colonies. Three or four were

on their way to West Africa; one or two to the West Indies and the South Pacific,

and rather more to each of the colonies in East Africa.

Of the eight of us destined for Tanganyika, I knew only Harry Magnay,

who had been at John’s in Cambridge but had had a different circle of friends

to me although we had come across each other from time to time on the rugger

field and elsewhere. We were naturally drawn together when in our last two or

three terms we had discovered we had put our names down to join the Colonial

Service and work in the same colony.

Our little Tanganyika group worked together and as one class studied

Swahili and the local anthropology and ethnology. We expected to go out and

serve together, and got to know each other pretty well in those months on the

Course. I am proud that they all became my very good friends in the course of time and I have remained in touch with them all my life. We called ourselves

the ‘Haidhuru’ - which is the Swahili term for “it doesn’t matter” - we searched

one day for an apt word and I can’t remember why we chose this particular one

which hardly seems appropriate, but for one reason or another it has stuck to

this day.

What were my first impressions of them all? Roy Bonsell was a northerner,

a tough well-built and cheerful chap with short fair curly hair and a wry smile.

John Illingworth of Trinity College, Oxford, was also from the north. With dark,

curly hair, he was a slim fellow with lots of humour. Charles Thatcher was the

tallest of us with a quiet and thoughtful demeanour. Simon Hardwick at Oriel

College was the wiry type and soft spoken but with massive determination. He

had a gammy arm as a result of polio during his army service in Germany but

never allowed it to be a handicap. Pat Hobson was at Magdalen, had had a very

tough National Service, and was the extrovert among us, a big man with a large

laugh and a generous nature. Norman Macleod was a Scotsman from a Scottish

school and university who had trained as an advocate and the law was his first

love. He was a reserved and gentle man, not one to be hustled or hurried, yet

with plenty of drive and the ability to enjoy life to the full. I am happy to have

been a member of that special group.

The Colonial Service Course

The Course I attended had its origins at the end of the war when the Duke of

Devonshire had reviewed recruitment and training for the Colonial Service. He

had recommended that all new recruits, to be known as ‘probationers’, should

attend a year’s course of training at Oxford, Cambridge or London University

before starting work as Cadet Administrative Officers in their chosen colony.

Originally known as the Devonshire Course, its purpose was stated to be:

“To give the Cadet a general background to the work which he is

going to take up; to start him with a proper sense of proportion; to show

him what to look out for in his apprentice tour and the significance of

some of the things he may expect to see during it; and to give him the

minimum of indispensable knowledge on which to start his career.”

In my letter of appointment, I had been told the Course would cover the

following broad subjects, on which I would be examined at the end of it: Colonial

History, Colonial Government, Criminal Law and the Law of Evidence, Land

Use in the Tropics, Social Anthropology, Economics and most importantly,

the Swahili language. As had been the practice when studying for our degrees, we were required to read a number of books and write an essay on a selected

relevant topic after a week or ten days. The pressure was never as intensive as it

had been with the Tripos, but we still had to get through a great deal of material.

The literature on colonial administration, government and the economics of

the undeveloped world was extensive, and we were expected to know our way

round it and master the key ideas in our year at Oxford. To some extent I had

an advantage having read ‘The Expansion of Europe’ for Part II of my Tripos,

but there was much much more to absorb. The bookwork included numerous

Government White Papers, Blue Books and official Reports of various sorts, as

well as Social Anthropology which was new to most of us. We were introduced

to the study of the life of communities and of social and tribal systems and

customs around the world, and especially in East Africa. We were told the

principal characteristics of the Tanganyikan tribes and picked up a good deal of

knowledge about them in our reading. This was directly relevant to our future

work and for most of us was fascinating from the start. We spent time too in

studying the origins and nature of Islam, the religion of much of the East African

coast, and had a searching exam at the end of the Course of our knowledge and

understanding of tribal structures.

Colonial economics was another new area of interest, and of course vital for

us to grasp. Some of the group found it easier than others, I suspect. For me,

my background in economic history helped. I became happier as the Course

progressed and got a grip on the Tanganyika Government’s financial reports,

estimates and development programmes.

Part of the Course was an attachment to a local authority and a police force,

and this took up most of the 1957 Easter break. Through my father’s contacts

I spent a week with the Luton Urban District Council and drove around with

a water engineer inspecting drains and the like - very dull work I thought it to

be. I spent another week with the Bedford County Council and their Education

Authority visiting schools and libraries to see how they were run. More

interesting were a couple of days spent at the West Central Police Station in

Savile Row behind Austin Reeds. We also spent time sitting in local magistrates’

courts watching the working of justice in England. These visits helped to bring

the Course to life and to put flesh on the bones - as it were - of the heavy books

we ploughed through over the three terms of study.

‘Land use’ was a complete different sort of subject. Unfortunately it was

treated as a poor relation and tended to be squeezed into the late afternoons

which was a shame because it eventually turned out to be the most useful and important instruction that I received that year. We were taught what you might

call basic farming - planting, cultivation, crop rotation, irrigation and so on. In

addition, an experienced teacher named Mr Longland, gave us the rudiments of

surveying, a little forestry, and the basics of building a road, a house, a dam, a

bridge, and the like. There were even a few lessons on vehicle maintenance - and

I wish I had paid more attention to them.

The ‘Law’ element in the Course interested me enormously. By the end of

it we had to have a fair idea of the Criminal Law and the Law of Evidence

prevailing in Tanganyika. It went back to the 1920s when it had been modelled

on the Indian Criminal Code, which reflected the English Common Law of the

day. We expected to be magistrates in our new job and were obliged to learn a

great deal of legal terminology and theory quickly. In addition we had to have at

our finger tips much detail of the relevant Tanganyika Statutes.

Language was an integral element of our Course. We were required to pass

the Elementary Swahili Exam before we finished at Oxford. Our teacher was

Bobby Maguire, a former member of the colonial administration, always smartly

turned out, with a military bearing and moustache, and an extensive knowledge

of the East African coast and of the language. He was a genial and hospitable

man who invited us more than once to his home. He and his wife lived in a

comfortable old stone and oak-beamed cottage in the middle of the village of

Thame with a long and beautiful garden where we much enjoyed his hospitality.

Mr Maguire was assisted by Abdallah, who came from Mombasa and helped

us with the spoken word and our accent. Our group spent a great deal of time

with these two, going through the bones of the language and gradually building

up our vocabulary. Swahili is not difficult to learn in the sense that it is spoken

as it is written, and there are few irregularities. Once one grasps the basic

structure, the rest falls into place. Our instructors were straightforward, clear

and systematic in their approach; they were patient, friendly and humorous too

in coaxing us through the problem areas; and as a result we all did well in the

end-of-course exams.

Our lectures tended to be held all over the city and in some out-of-the-way

places like the Forestry Institute, and the College of Technology. One morning

we might be at Queen Elizabeth House, and the next at the School of Geography;

sometimes we were at lecture rooms along Keble Road; at other times in colleges

such as Wadham and Nuffield, at Rhodes House itself or in the Club. The

variety of our subjects and of the teaching locations was part of the fun. Some

of the more important events were held in the evening - we became members of the East Africa Association and went to lectures on general topics by prominent

speakers like Margery Perham and President Azikiwe of Nigeria.

Having recently spent some time in Germany and become interested in their

language, I took German conversation in the evenings once a week at a private

house in the city. This was very much an extra-mural activity that I enjoyed

and helped later when I wanted to read the original literature of the German

occupation of Tanganyika. Sadly I never mastered conversation and forgot it all

in a very few years.

Tanganyika

I also read as much as I could find about the system of administration in

Tanganyika. It had been developed by Lord Lugard in West Africa and Sir

Donald Cameron in the East, and was known as ‘Indirect Rule’. Chiefs, and

federations of chiefs, were recognised to run local government through their

tribal structures of petty chiefs and headmen. Their Native Authorities raised

their own revenue from fees and taxes to spend on local development and

administration, while native courts were empowered to settle civil and minor

disputes. The DC had ultimate authority while supporting and advising the

system. He was also a magistrate with significant powers in criminal cases; he

had responsibility in most areas for the police and prisons; and he was Head

of the District Team which could include specialist European staff with duties

concerning agriculture, animal health, construction, nursing and medicine. In

each district the DC could normally dispose of one or two District Officers

(DOs), of whom the junior was often a newly-fledged Cadet which I was to

become.

It was necessary to learn about the country in which I was to serve. The

Germans had occupied Tanganyika in the 1880s during the so called ‘Scramble

for Africa’, had brought law and order to the country, building forts known

as ‘Bomas’ in all the population centres, ending the mainland slave trade, and

putting down rebellions with great severity. They had developed Dar es Salaam

as the capital city, built railways across the colony, and introduced sisal and

coffee as cash crops. The British had kicked them out in the Great War and

the country had become a British Mandate in 1920 and UN Trustee Territory

in 1946. The Trustee Agreement required the colonial power to promote the

development of free political institutions, and to ensure equal treatment for all,

subject to the political, economic, social and educational advancement of the

inhabitants. The country was at that time administered by a Governor, assisted

by an Executive Council (Exco) of eight official and six unofficial members. Laws

were enacted by the Governor with the advice of the Exco and the consent of the

Legislative Council (Legco) of thirty-one official and nominated members and

thirty unofficial members (MLC), ten each being European, Asian and African.

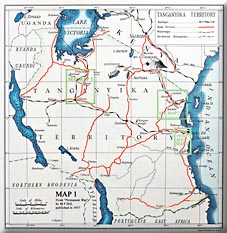

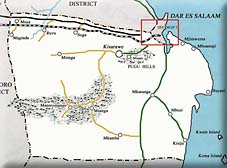

The country was the size of France and divided into eight provinces, run by

Provincial Commissioners (PCs) reporting to the Governor, and further divided

into fifty-six districts under District Commissioners (DCs). At Dar es Salaam

was situated the Secretariat under the Chief Secretary who also responded to

the Governor. Second in importance to Dar was the port of Tanga to the north.

The other Provinces were:

| Province | Main town(s) | Principal tribe(s) |

| Central | Dodoma | the Gogo |

| Lake | Mwanza | the Sukuma |

| Southern | Mtwara & Songea | various |

| Western | Tabora | the Nyamwezi |

| Eastern | Morogoro | the Luguru |

| Northern | Arusha & Moshi | Masai & Chagga |

| Southern Highlands | Mbeya & Iringa | the Hehe |

Word reached me that I was to spend my first tour in Songea in the south,

and I read as much as I could find about the Southern Province which seemed

to be in many ways the most remote and farthest backward part of the Territory.

Balliol College

My membership of Balliol was important but took second place after the

Colonial Service Club. At the College, I attended freshmen’s and other graduate

meetings and found my way to the library and the Hall where I dined several

times a week. I was invited to meet the eminent Master and other college

dignitaries but I had no ‘tutor’ in any sense in the college and I did not much

mix with the undergraduates except in sport. I grew, however, to know and

enjoy the company of a number of graduates of my vintage, and played bowls

on the lawn of Balliol First Court with a pleasant crowd on many a fine evening.

The College provided me with useful opportunities for sport. I joined

a scratch rugger team of those who were enthusiastic without being either

particularly tough or skilful. With these chaps I was able to have some pleasant

and challenging games - on the wing as usual - through the winter months. The

last game of the season was a friendly match played on a fairly rough pitch in

what were known as the University Parks, not far from where I was living. Half way through the game, the ball came my way out on the left wing. I ran forward

and lunged towards it with my hands outstretched ready to grasp it. Someone

from the other side who was racing me to it, took a hefty kick to it, missed it

and connected with my head. I was dragged unconscious off the pitch and left

on the grass by the touchline under someone’s coat while the game went on. I

woke up and felt no ill effects apart from a headache. I regained my place on the

field and carried on with the game - though I doubt if I took much further part

in it. I had no suspicion of the way in which that kick would caused me serious

problems later on.

I went on to row in a Balliol boat on the Isis during the Trinity Term - as

Oxford styles the summer term - and enjoyed myself hugely. I was once again in

the college ‘rugger’ boat and there promoted to no. 7 in the boat immediately behind Stroke. This was a much more responsible position than bow had been

- indeed I was put in the ‘power house’ of the boat which seemed strange as I

was still one of the lightest men aboard and my experience was modest, but at

any rate I enjoyed the river. Our boat was Balliol IV (Balliol was a lot smaller

a college than John’s and had only five boats on the river that summer whereas

LMBC at John’s had eleven), and we started the May Races high up on the water

in Division VI. We rowed over satisfactorily on the first afternoon, but were

bumped on each of the following three days by boats from Worcester College,

Merton and Jesus successively. We worked very hard but failed dismally. Our

poor performance was eclipsed only by Balliol’s First Boat which started as Head

of the River on the first day of the races, was bumped four times and ended up

on 1st June a long way from the top. It was a disappointing year for the College.

There was not much to celebrate at the ‘Bump Supper’, though it was still a

good party.

Lodgings

It was a pity but understandable that the College could not offer me

rooms in college or at their lodging house at Holywell. During my first term,

I rented digs in a quiet terraced house off Walton Road, up behind Worcester

College and the Ashmolean. It was a dull little single bedroom looking on to

a back yard, sufficient for my needs but rather lonely. I missed the evenings of

conversation with coffee and beer, the bridge and the frequent cheerful parties

of my undergraduate years.

After one term, Harry Magnay I decided to share a flat, and found a suite of

rooms on the first floor of a big Victorian house at the end of a quiet cul de sac

in Norham Road in Park Town. It was within walking distance of some handy

shops on the Banbury Road, of the Club in South Parks Road, and of Keble

Road where a number of our lectures took place. On one side of the landing was

a big living room with good sized windows looking over the front garden, and

the other side was a kitchen that also served as a bathroom - a board came down

over the bath to provide us with a table for our breakfast. It was ideal except

for one thing. I had not realised that Harry was wooing Hilary. Harry was an

extrovert and thoroughly enjoyed a party, but he kept many things to himself,

including his love affair. I enjoyed Hilary’s company for she was a very friendly

person, and I was delighted to find her in the flat when I came in at the end of

the day, but I was green about affairs of the heart. I was completely taken by

surprise when Harry told me one day he would like me to move out of the flat because he was going to marry Hilary. I had quickly to find an alternative for

my final few weeks at Oxford.

I bought a car - a tin box of an old Austin that cost a very few pounds and

sometimes ran quite well. I trundled over to Monkey Island from time to time,

notably for a good party on Guy Fawkes Night and the following weekend.

I drove across to Cambridge to see old friends there on several occasions; the

warm-hearted Girton ladies invited me to a big party at the University Arms

Hotel in January, and I went to another party in mid June not long before we

went down. Better still, I went over for the John’s 1957 May Ball, using Girton

College as the base and meeting other friends again.

I was also able to drive down to Town for one or two parties - Dansie gave

us a very smart dance that November, and I was able to spend time with my

sister Margaret and the children in Willow Road. The car did however have

a tendency to break down; I was taking Pat Hobson over to Cambridge on

one occasion when the big end went with a dreadful clang and stranded us in

the depths of the Hertfordshire countryside. Worse still, the petrol rationing

introduced at the time of the Suez Crisis curtailed my extra-mural activities

(Anthony Eden’s abortive invasion of Egypt led to oil sanctions, among many

other inconvenient things). Then, even more maddeningly, when parking the

car in a dark corner of the garage where it was kept when not on the road, I

backed it into an unmarked open inspection pit. The garage proprietor hauled

it out and reported gloomily that back axle had been bent, so I had to be very

careful with it thereafter and sold it eventually for next to nothing.

Social Life at Oxford

There was always masses going on in Oxford, as there had been at Cambridge.

I saw a certain amount of two old Shirburnians who were still up, James Maas

and Mike Duffett, and they helped me find my way round the university in my

first few months. I joined the Oxford Union, as I had the Cambridge Union,

and listened to the debates. There were excellent shows at the theatre that even

attracted Liz and her Monkey Island friends who came over for the Sadlers Wells

Ballet when it was in the city.

My social life soon however began to revolve around the Club, the other men

who were on my Course, and the Haidhuru who were destined for Tanganyika,

We were all constantly in the Club-house where, besides our own group, we were

able to enjoy the company of those going out to other colonies, notably Uganda

and Kenya, whom we met for drinks and a game of billiards and even a couple of dances. We also visited each other in our colleges. John Illingworth invited

us to Trinity College where he had rooms. Simon Hardwick threw a couple of

cheerful drinks parties in his beautiful Oriel College and gave us an excellent

dinner there - where I well remember how we enjoyed the college’s Muscadet,

eight year old Santenay and twenty year old Sandemans Port. I played bridge

once or twice with Charles Thatcher and others, and Charles entertained us all

at his parents’ home not far from Oxford.

I discovered that several of my contemporaries were on the point of getting

married. We had all been warned that Cadets were not permitted to be

accompanied by their wives during their first two years of service in Tanganyika,

but nothing discouraged my new friends from actively pursuing marriage with

the girls of their choice. Harry met and married Hilary and kicked me out

of the flat. In addition, Norman Macleod wed Jane Bromley (sister of John

who had been a friend at St John’s College), Charles Thatcher married Susan,

and Pat Hobson became heavily involved with Penny in amateur dramatics

and numerous artistic activities at Magdalen College. Pat and Penny were very

hospitable and we were all delighted when they announced their engagement in

June, and we had an excuse for some very happy celebrations.

The final weeks at Oxford

All too soon we were plunged into a round of exams to check our knowledge

of the key course subjects. Law was probably the most difficult and required

the most careful revision; and Swahili, both oral and written took up the most

time. We all passed all the exams which we sat in the third week of June, at the

conclusion of the Course, starting immediately after my return from the John’s

May Ball. I was awarded 70% in the Swahili which was pleasing and suggested

I had been well taught.

There was a flurry of farewell parties and I came down from Oxford for good

on June 26th. The next day was a Saturday and it was Sports Day at Michael

March’s prep school. I drove there and was shown round and had a delightful

day - in loco parentis, as it were.

A letter dated 2nd July reached me at home from the Colonial Office which

read:

“I am directed by Mr Secretary Lennox-Boyd to …say that a

satisfactory report, following your course of instruction at Oxford

University having been received, your selection for appointment to

the service of the Government of Tanganyika on probation as an

Administrative Officer (Cadet) on the terms communicated to you…

has been confirmed.

The Crown Agents …are being asked to provide you with a passage

to Tanganyika on the “Warwick Castle” which is due to sail on the

24th July….I am, Sir, Your obedient servant,.”

I had to organise myself for my departure. With an outfit allowance of £45

I had a great deal to buy with which to fit out my future home in East Africa.

I purchased linen, blankets, crockery, kitchen gear and tropical clothes. In

addition, Uncle Francis generously gave me his double-barrelled shotgun and

his old golf-clubs. We were recommended to use Bakers, the forwarding agents,

located in Golden Square in Soho. When all my kit was assembled, I dumped it

all on Bakers who packed it in wooden crates and tin trunks and arranged for it

to be loaded onto the ‘Warwick Castle’ and put in the hold on my behalf.

I managed to fit in a couple of Luton dances and a weekend in Aldeburgh

sailing at the Yacht club on the river Alde with Graeme. I sold my car - for a

pittance; I packed a trunk to take with me in my cabin; I did the round of

relations to say goodbye - especially to Caryl who was off to Australia; I sorted

out my affairs at the bank and collected travellers’ cheques for the voyage. I was

ready to go.

The final weeks at Oxford

Thus organised, I was able to join my parents, John and Doreen, and Peter,

Susan and Bill at a farm on the edge of the South Downs in Sussex for a few

days of complete relaxation. Horton Hall Farm was a very smelly chicken farm,

but peaceful and comfortable. We all had fun on the sands of Shoreham; and

I played a little (bad) golf with my father, called on cousin Joy and Ray Doyle,

and drank their beer out of tooth-mugs. Liz came over and went off to look at

a house for sale to see if it would be suitable for her new venture - a children’s

home. We had an afternoon at a local swimming pool - Peter swam beautifully

- and a picnic and family cricket. It was a memorable holiday with some happy

children, and I was sad to say goodbye for what I expected to be three years.

Mother then drove me up to Hampstead where we found Margaret, Robin

and Lally all unwell, and had a drink and supper with Roger in a local pub.

More goodbyes. I then spent what I assumed would be my last night in Brooke

House. More packing; and my father, suffering from a painful toothache, drove

my mother and me in the Wyvern down to Shed 12 of the King George V docks

where the ‘Warwick Castle’ was waiting for me.

The ‘Warwick Castle’

On arrival at the docks on the afternoon of 24th July, 1957, I found myself

hustled aboard by taciturn and unhelpful customs and immigration people.

There was no time to say goodbye; I was not allowed to go back down to

the quay nor were my parents allowed to join me aboard. It was a messy and

unhappy departure.

The ship cast off in the late evening and spent an hour leaving the docks

through a lock into the river while all of us leant over the rail - and the magic

and mystery of a sea voyage gripped us so that even the dirty, smoky and very

smelly London dockland looked romantic by night. Thus the ship entered the

river Thames and turned east to sail down river into the North Sea, with the

promise of four weeks afloat, of which three would be spent at sea and one in

ports along the way.

That first evening, I sorted myself out and tracked down my colleagues

bound for East Africa. It was pleasant to meet them all again - looking very fit,

all rather excited while trying not to feel sad, as we all undoubtedly did, sailing

away from our families at home. We were in the Tourist Class and shared small

two-bunk interior cabins. I had the upper bunk above Roy Bonsell who was

an easy and pleasant companion. We had sufficient room for our suitcases and a decent-sized wardrobe. The food was not bad, and the lounges and bar were

adequate, but the Tourist Class deck space was small and pretty nauseous, being

aft of the funnel and the kitchens.

We quickly established a routine while sailing. A cup of coffee was handed

to us in our bunks in the cabin every morning at 7.15; breakfast was always

deliciously satisfying, lunch was rather average, the afternoons were lazy, and

our group all bathed and changed into a suit before dinner. In the evening,

entertainment was often provided, either by a little band for dancing on the

deck under the stars, or with a film on a screen rigged up aft. During the day we

played deck tennis in the open air, or cards or ‘liar dice’ in the smoking room,

or sat in the bar drinking and talking at almost any hour of day or night - and

we talked an awful lot. The few girls travelling on the ship were a friendly crowd

and made dancing and social life very pleasant. On Sundays the Captain held a

church service in the First Class lounge and we all went to it, partly in order to

pass the second half of the morning in the First Class bar.

The space for deck tennis was limited but it was the best way of getting

rid of surplus energy. Deck quoits was considered an old man’s game, but was

also entertaining. A canvas swimming-pool was erected as soon as we reached

warmer weather but it was minute and grew dirty quickly with the kids playing

about in it. So some of us nipped into the First Class tiled bathing-pool on

the upper deck early each morning before breakfast when there was nobody

about. Mostly we kept cool by sitting in deck chairs in the shade - under lifeboats

or decking, and reading avidly. To keep myself from growing bored I read

the thousand pages of Tolstoy’s “War and Peace” on the ship, and spent time

each day brushing up my Swahili and looking at the “Teach Yourself ” book of

Arabic. I kept a diary and wrote countless farewell and thank you letters during

the first week to post at each port of call. In addition I bought every English

newspaper I could find, and went through them and their crosswords avidly.

Gibraltar was our first stop. Seven of us hired an enormous taxi and were

driven all over the Rock. We were taken down to the frontier, round the

defences and across the airfield that ran into the sea on both sides. We looked

at the beaches behind the Rock and the tunnels that had been dug through

it during the War. We went up the cliff face to admire the view and inspect

those unpleasant apes - nasty, aggressive creatures. After exploring the caves

overlooking the Spanish frontier, we paid off our driver and wandered round

the dull and dusty town. It was a hot and uninspiring visit.

At Marseilles several of my group took a bus out to the quiet beach at Cassis

for a bathe and picnic. We found a delightful spot in a cove nestling between

picturesque cliffs where the sun was warm although the water was surprisingly

cold; and following a refreshing break we took a taxi back to the boat.

Genoa gave us two days of glorious weather when we were able to treat

the ship as a hotel, leaving it in the early morning, returning for dinner each

evening, and going out into the city again to round off the day in one of the

many delightful cafes and bistros in the old town with their cheap and tasty

Chianti. We split up during the day into little groups, but often met for the

afternoon at a pre-arranged beach along the coast.

John Illingworth and I hired a Vespa motor-scooter, which ran us around

very comfortably for about 30/- each including petrol. We buzzed along the

coast road to Rapallo, finding several pleasant spots free of tourists, where

the Italian Riviera was very attractive and the Mediterranean very warm. One

day, we took our Vespa inland high into the Ligurian Alps. We covered some

sixty miles of fascinating country, before returning downhill to the coast for

an afternoon swimming and lazing at Portofino. We were sorry to have to say

goodbye to our Vespa and Genoa when we set sail again.

The ship cruised down the west coast of Italy and sailed close enough for

watchers on board early one morning to see flashes from the mouth of the

volcano, Stromboli. Around 6.30am next day the ship passed through the

narrow Straits of Messina, with Mount Etna in the distance, seemingly covered

in snow. Thereafter the ‘Warwick Castle’ left the land, the weather warmed up

in the eastern Mediterranean, and passengers changed into shorts and tropical

dress.

At Port Said, despite the British invasion only a few months earlier, we were

allowed ashore, the shop-keepers were delighted to see us but their shops were

empty. The shelves were bare in Simon Artz, the famous dock-side multiple

store; in the town many other shops were closed; the paint on all the buildings

was dirty; offices stood empty amid broken glass; town houses were tightly

shuttered; and in general Port Said looked pathetic.

The new mosque was the only public building worth seeing, but its tower

was unsafe after the bombing before the invasion. Visitors were not permitted to

see the area of destruction; we were sent instead to visit the Catholic cathedral.

The verger said that the church’s congregation had stood at six thousand people

before the invasion and been reduced to fewer than six hundred unhappy Greeks

and Italians. The European residential area of the town was deserted - all means of livelihood gone. Along the quay, the Egyptians had tried to destroy the De

Lesseps statue and the remains of several wrecks lay around the harbour mouth.

At what had been one of the superior tourist hotels on the corniche, we drank a

beer with a few friendly Canadian UN soldiers.

That night the Canadians took us to one of the remaining night-spots where

we were well served and entertained with dance music. A cabaret of muscular

dancing girls did terrifying contortions with their tummies. We were highly

amused and came away happily in a great crowd. Pedlars sold roses with a

beautiful scent at a shilling a bunch, so we returned on board with bunches

of sweet-smelling red roses and a friendly feeling towards Port Said despite the

unsavoury impression of the afternoon.

All the following day the ship was part of a long convoy going down the

Suez Canal. We leant over the side for hours, looking at the sand, palms, camels,

donkeys, dirty little villages, and units of the Egyptian army in training by

barracks on the shore. I was reluctantly roped in to a whist drive after tea, and

thus missed most of the sights of the southern half of the Canal, and emerged

from the smoking room in time only for a last glimpse of Port Suez. That night

we entered the Red Sea, and for the next three days had only one thought - to

get away from the heat. The temperature went up to 108 degrees in the sun on

deck. The days were intolerably hot and humid and the cabins were unbearably

stuffy. A light breeze blew up, but failed to reduce the humidity or penetrate the

cabins.

The ship steamed into Aden harbour for bunkering, but to our regret, no

shore leave was permitted. A case of polio had been diagnosed on board. A dark

cloud seemed to hang over the ship; people with headaches and coughs were

isolated, and the swimming baths and children’s nurseries were closed. Social

life continued however while the ship steamed onward for ten days without

docking. Competitions started on deck and we all took part. I survived the first

round of the deck quoits mixed doubles, but failed badly in the deck tennis

singles to a fat South African. We played a great deal of liar dice, and began to

play bridge in the afternoons and evenings. Charles was an experienced player;

Simon was thoughtful; I was beginning to grasp the essentials; and one of the

others was always prepared to make up a four.

Most of us slept on deck, rose each morning with the sun, and slipped into

the swimming pool for a quick refreshing bathe. We woke one morning to feel

a stiff breeze blowing spray over us and to see Cape Guardafui on the starboard

beam. We were in the Indian Ocean and feeling the effects of the southwest monsoon. The breeze freshened, the sea grew rough and we had to contend

with sea-sickness among the passengers, especially the children. As we drew near

the Equator, it rained and grew much colder. It was exhilarating to stand in the

ship’s bows, forward of the First Class lounge, in the face of the tearing wind.

The colour of the sea was black, with huge troughs in the waves; dolphins played

in it and silver-backed flying fishes flitted across from crest to crest of the ten

foot high waves, as we ducked the plumes of spray splashing across the deck.

Gradually the sea calmed down and the wind weakened. We celebrated

‘Crossing the Line’ with numerous festivities. Dinner was a gay and noisy affair

as we officially crossed the Equator, and our meal was followed by a fancy dress

parade and dance. As there were eight of us, we Haidhurus decided to turn

ourselves into Snow White and the Seven Dwarves. I was elected on a vote of

seven to one to be Snow White. The girls put me in a white bridesmaid dress

with black and white crinkly paper for bodice and apron; and the ensemble was

completed by a huge black wig. The dwarves were most impressive - six foot tall with gumboots, pyjamas, woolly berets and pickaxes. We marched on, sang

our little song ‘Heigh Ho….” ad nauseam, and to our delight were presented

with the prize for the best group. Some of the individual costumes were quite

excellent; prizes were presented; the band played and we danced. When the band

stopped we went on deck and sang songs to a banjo; then at some unearthly

hour in the morning a few of us invaded the galley and were given cups of tea

and sandwiches by the cook on duty; and we went on talking for hours more.

On the final evening before reaching Mombasa, Harry and I threw a small

farewell cocktail party to say goodbye to our fellow cadets destined for Kenya

and Uganda and the girls whose company we had much enjoyed. They were

to disembark at Mombasa where the train would take them up to Nairobi and

Kampala. We invited thirty guests among our friends and gave them South

African wine with a dash of Benedictine and an excellent buffet provided by

the ship. Our party was followed by others that night and someone’s belated

birthday, so that it was very late before we spread our lilos under the winches for

a few hours sleep, before entering harbour in the early morning.

Mombasa

For most of us, Kilindini docks at Mombasa were our first sight of black

Africa, and inevitably rather unprepossessing. We hung around the gangway

to the shore to say goodbye to those disembarking to catch the train and to

watch the cargo being unloaded - Fiat cars, Vespa motor cycles, Dewars whisky,

asbestos sheets, and masses of heavy crates.

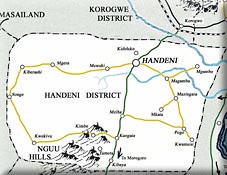

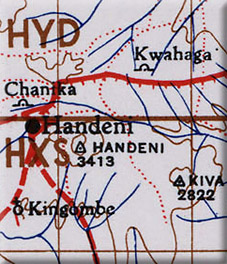

Then the mail came aboard. In addition to a long letter from home, I was

handed a note from the Secretariat in Dar es Salaam to say my posting had been

changed. I was appointed to Handeni District in Tanga Province instead of the

Southern Province. This meant I had to disembark at Tanga, the next port of

call, instead of getting off the boat with the others at Dar es Salaam. The change

of plan was confirmed in a friendly letter from the Handeni DC welcoming me

to the District. In a great flurry and flap I busily replied to the official letters and

arranged to pack my belongings and extract my tin trunks, baggage roll and gun

from the ship’s hold much earlier than expected.

While I was with the purser and stewards, Charles and Harry went ashore

and hired a car - a nice-looking Morris traveller. Six of us piled in and went for

a spin to look at the city and the countryside beyond. We drove out to the Nyali

Beach Hotel, flung on our bathing trunks and rushed into the sea, splashing

around like schoolboys in the warm water. It was a glorious bathe; and we were all singularly content with life, having just about reached our destination, and

the culmination of four years of study and training. We went out in the car

again after supper on board, parked by the Mombasa Club and strolled around

Fort Jesus, looking at the Court, the cathedral, the hotels, and the old Arab

houses with their heavy brass-studded wooden doors.

Next morning, we found the ship half-empty and planned a safari to look at

game in the Reserve up-country. We raided the baggage room for bedding rolls,

blankets and camping gear; Charles wangled a store of food and a couple of

bottles of wine from the ship’s cooks; and off six of us went - over the causeway

and up the road to Voi. We started through a green and fertile belt among the

coconut palms, but the tarmac quickly gave way to a dust road of ruts and

corrugations. Along the roadside, the children were naked and the women bare-breasted,

carrying cans of water and foodstuffs on their heads - we were truly

in Africa.

At Voi we consulted the Game Ranger at his workshops and entered the

Reserve. Herds of deer and gazelle were wandering by the roadside; then

close to the track was a tall and stately giraffe gently grazing among the thorn

bushes. My heart stopped. The thrill of first seeing animals in the wild was

indescribable. This was a moment of supreme excitement and pleasure - and it

was compounded many times as we drove on. Our joy was mitigated a little by

poor Harry who was feverish and whose nose bled copiously into the dust when

we paused for a very late lunch. We had to go back to Voi to refuel and then

drove deep into the Reserve to the Safari Lodge at Aduba Dam where the water

attracted the animals. It was late when we reached the rest-house, tired after

frequent pauses to watch herds of elephant; and it was somewhat disconcerting

to find it already occupied. We put up camp beds in the kitchen and store-room

- I chose to sleep in the car which was not a success. Our uncomfortable night

was nevertheless exciting as, for the very first time, we heard the bumps, growls,

squawks and barks of creatures in the bush around us.

We were awake early and took the car to the dam at first light to watch the

animals come down for their early morning drink, notably herds of elephant and

a group of fierce-looking buffalo. We stayed there for a long while as the animals

drank greedily and their young played at the water’s edge. We followed them in

the car as they withdrew and drove on round the circuit of the Reserve, passing

the Lugard Falls and a stretch of the Galano River, seeing other elephants, more

tall giraffe, all sorts of deer and buck, and numerous monkeys. As we emerged

from the Park, we called at Tsavo but it was a miserable place and offered nothing so we drove back to Voi for much-needed sustenance and a wash, and Harry

then motored us down the dusty, bumpy road back to the ship.

After food on board, we went back out to Nyali Beach where the ship’s

officers in starched white monkey jackets and others from the boat in black ties

were dancing under the stars and coconut palms to a very gay band. We were

not dressed for such a smart party so we walked along the beach chatting and

enjoying the evening breeze. Crabs were everywhere in the sand scuttling in

and out of their little burrows. Someone decided we should catch some in a bag

and scatter them on the dance floor to cause a little confusion among the partygoers.

Norman and John caught half a dozen while I laughed at their antics.

We went back to the hotel bar for a much-needed drink, and the little brutes

escaped, so we never discovered the effect they would have had on the dancers;

instead we drank and talked the night away.

The next day was Sunday and the ship was dead, so five of us went back to

Nyali to a service at St Peter’s church. It was a wooden, open-sided and thatchroofed

building where the Africans sang the hymns in Swahili with tremendous

gusto - it was grand to see such enthusiasm - and the pleasant young parson

preached an encouraging sermon. This was my last day aboard, and I spent the

rest of it writing letters and packing. In the evening we had a final and formal

Haidhuru drink as we expected it to be the last occasion on which we would

all be together. I went to bed that night tired and apprehensive about what was

waiting for me next day when we docked at Tanga. I was to land there and at

long last assume the mantle of a District Officer in the Colonial Service on full

pay.

Off Tanga

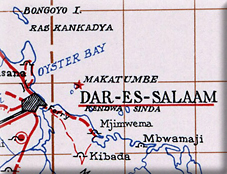

By the time I woke next morning the ship was already at anchor off Tanga.

The harbour was too shallow for the ‘Warwick Castle’ to go alongside so we

sat in the bay some way off shore where I had my first view of Tanganyika.

In the bright sunlight, I saw a sandy beach, shaded by coconut palms, a few

white office blocks and scattered houses among the trees that looked like official

residences, a sailing club, a dock for small boats, cranes and a jetty. A little green

island lay in the foreground; behind it to the right and to the left as far as one

could see, stretched a thin green strip of mangroves in swamps marking the edge

of the land - and miles and miles of nothing much else.

I dressed in clean white shorts and shirt and was called down to the smoking

room to meet the Immigration Officer. There I joined Norman Macleod who was to go ashore with me and was posted to the town of Tanga itself. A man

called King introduced himself to us as Office Manager at the Tanga District

Office and explained he had come to collect us in his land-rover. So we had a

hurried breakfast, made our goodbyes, and climbed with him down into a small

boat that carried us to the jetty. Our suitcases were waiting for us in the Customs

Shed, and we could only hope our heavy luggage was being transferred to a

lighter to be brought ashore at the docks later on. The young Indian customs

officer was friendly and passed us through rapidly; and we emerged into the

sunlight on a dusty road in Tanga to start life as District Officer Cadets.

|

|

Chapter 2: Handeni

|

|

“It would be hard to find another job, then or now, that gave

responsibility and satisfaction in equal measure at so early an age,

or a lifestyle that was as rich in enjoyment as it was rewarding in

fulfilment.”

J. H. Smith CBE, in a foreword to “”Symbol of Authority” by

Anthony Kirk-Greene.

Landing at Tanga

Mr King told Norman and me a little about Tanga as we came ashore. It

was the headquarters of the Province of the same name which comprised five

Districts including ‘Tanga Town’, ‘Tanga Rural’, and Handeni that was the

poorest of the lot. He loaded us and our bags into his land-rover and whisked

us through the town along the shore to the Provincial Office, a huge solid old

white building looking out to sea. There we were hustled in front of the Deputy

Provincial Commissioner (DPC) to say how d’ye do, and then into the big cool

wooden-floored high-ceilinged office of the PC, a big whiskery fellow named

Shaw. He welcomed us warmly, spoke to us briefly about our postings and future

exams and sent us off to meet his secretary who had letters and messages for us.

We were then taken down the road a few yards to the Tanga Boma, the

District Office, which was a converted garage that had been smartened up and

provided offices for two DCs. We were introduced to Reed, known as ‘DC

Urban’ who was to be our host for the next day or two in his bachelor quarters.

He had a military bearing and was the strong silent type. The ‘DC Rural’

was named Alan Brown, who was a complete contrast. He was a small chatty

Scotsman, a pleasant, friendly man and was to be Norman’s immediate boss.

Alan talked with us for a while about the work of his District and then sent us

off to the Standard Bank to open bank accounts and arrange overdrafts until our

salaries and allowances started to roll.

We found Tanga to be a compact, well laid-out township with shady

ornamental trees lining many of its roads. It was only three streets deep, but had

some fine old German-built houses including the Provincial Office, a hospital,

a quiet park along the harbour front, and a beautiful outlook seaward over

sparkling sands. Some commercial buildings looked new; the sailing club had

a bright and cheerful appearance, and a line of bungalows amid acacia trees

looked neat and cool. We saw the war memorials, and were reminded how the

British had sent an expeditionary force to land there unsuccessfully in 1914

which had led to considerable loss of life - I knew all about it because my father’s

senior partner, my Uncle Hugo, had been a member of the invading force as a

young man. The African market was noisy, scruffy, animated and smelly with

stalls of drying fish and raw meat covered in flies. The Indian-owned shops

seemed to stock everything we wanted and the European firms had convenient

offices. After a quick tour, we went first to the bank, then to the Police Station

to arrange licences for our guns, and on to the shipping agents to arrange offloading

of our trunks from the lighters out in the bay.

Mr Reed then took us to his home which was a large German-built property

with several big bare rooms with red polished floors, and one with a spacious

sunken bath. The house must have been put up as a mess for several young men

and the Germans had done themselves proud. Our host had two giant, voracious

and slobbering dogs, and he treated his servants in a terse and peremptory

fashion which surprised Norman and me. Even more surprising was the way

he allowed them to cook quite awful food. The steaks they served that first

morning were practically uneatable; the coffee that followed was undrinkable.

When I was shown my bedroom I found no sheets. Tea was almost as bad and

there were only two unbroken cups. The garden was wild and over-grown with

rank grasses. It was a strange and unwelcoming household for us to find on

arrival in the country - happily I never met another like it in my subsequent

wanderings around Tanganyika.

During our first afternoon I accompanied Norman to open up the house he

had been allocated by the Public Works Department (PWD). It was a pleasant

spot, and Norman who expected to be joined by his wife Jane before long was

satisfied with it, although it needed some urgent repairs. On making enquiries,

I discovered my heavy baggage would take a couple of days to be unloaded and

cleared by the Customs, and Mr Shaw, the PC, instructed me firmly to wait for

its appearance before setting off for Handeni, so I was unable to do anything

for myself except buy necessities and get some washing done. I was desperately eager to reach my station and start work, but I had to be patient. Happily we

discovered that Mr Maguire, our Oxford Swahili teacher, was in Tanga too. He

had flown out to spend some time in the country during the summer vacation

in order to brush up his knowledge of the language before the next ‘Devonshire

Course’. Norman and I caught up with him at the Palm Court Hotel, and found

him surrounded by our fellow ‘Haidhurus’ who had come ashore while the boat

remained in the harbour. We had not expected to see them again and were

delighted to do so, all talking at once as we gave them our first impressions. We

had a very relaxed and merry time and drank another toast to the Haidhurus -

and this was indeed the very last time all eight of us were together. The ‘Warwick

Castle’ sailed for Dar es Salaam late that night - while ashore Norman and I had

an uncomfortable evening following a ghastly supper of half-cooked fish.

The Governor

I spent next morning with Norman at his house, killing time while helping

him sort out his furniture and make a list of essential repairs for the PWD

to tackle - leaking roof, broken door frame and so on. We visited the Labour

Exchange where Norman hired a cook and a house-boy to look after him in an

amusing and interesting series of interviews. We were sitting in Norman’s office

in the Boma in the early afternoon working out salaries and expenses, when we

were suddenly summoned to go out to the air-strip to meet the Governor, Sir

Edward Twining. Apparently he had spent the morning with Alan Brown on

a tour of the rural district and wanted to meet us before flying back to Dar es

Salaam. So we were positioned beside his little three-seater plane to await his

return at the conclusion of his business in the District.

In due course his convoy of cars arrived and Alan introduced us to HE. He

was both larger and older than I had expected. Dressed impeccably in a light

grey suit, he appeared a little tired and worn, but was totally relaxed and very

cheerful in talking to us. He had a big laugh, a hearty manner, and a great sense

of humour, and was very ready to break off from his official safari to chat and

joke with us.

Addressing us both he said:

“How d’ye do. I’m sorry to bring you out of the office but I’m glad

to meet you this afternoon. I normally inflict lunch at Government

House on all cadets but you two haven’t been down to Dar es Salaam

yet. I’ve already met four of ’em there and I wanted to see what you

looked like.”

He talked about the speech he was going to deliver to the Legco in a day or

two that was obviously on his mind and told odd little stories about himself.

Then he asked us about ourselves, and this is how the conversation went.

Looking at me, he enquired, “Which are you?”

Me. “Eberlie, sir.”

Sir E.T. “Where are you going?”

Me. “Handeni, sir”

Sir E.T. “It’s a very quiet place. Lots of ‘fitina’ there. Do you know what that is?”

Me. “No, sir.”

Sir E.T. “It’s malice!”

Me, ever helpful. “And there’s witchcraft. I gather I’ll be bewitched.”

Sir E.T. “Oh, yes. My wife is thinking of setting up a school for witch-doctors.

And I wanted to form a committee on witchcraft and put Nyerere on it. Don’t believe

anything in Handeni. Believe nothing of what you hear and half of what you see,

and you’ll get on alright there”

Looking at Norman, “And you’re going to be in Tanga. You’ll like it. It’s an

interesting sort of place. Either a murder or a road accident every day.”

Looking at us both, “This is a wonderful country. This is a tremendous service.

They are the salt of the earth. You have the prestige and authority to do a good job

here. You’ve got to be a pretty dull sort to find it boring. Well. I just wanted to see you

chaps, and now I have! Goodbye!”

With that, the Governor scrambled into his plane; we waved him off and,

much elated by the interview, went back to Norman’s office to carry on with our

calculations.

That evening Norman and I were given a drink by the PC and met Mrs Shaw

in their very grand flat above his office overlooking the harbour, and we went on

to have supper with Nan and Alan Brown with whom we were already friends.

I thought them a delightful couple and envied Norman such a pleasant boss.

We got on very easily with them and I listened with great interest as Nan spoke

about social life in Tanga and Alan described some of his experience of Africa