|

|

|

|

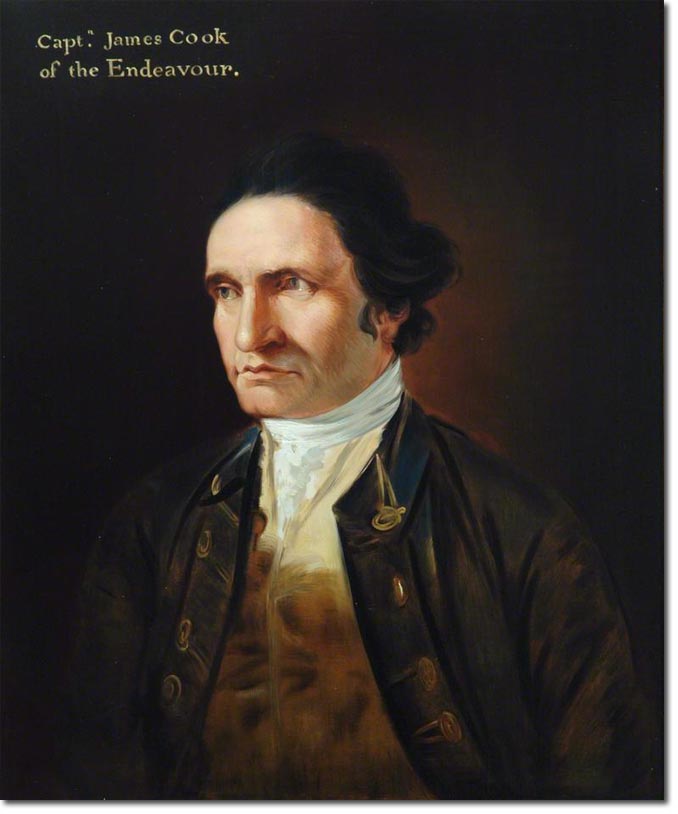

Captain James Cook was one of the most famous and most important explorers ever to leave Britain. His journeys in the Eighteenth Century were unlike any expeditions conceived before. They were scientific endeavours which were literally mapping the unknown world. Each of the three important expeditions departed from Plymouth and returned there also.

After completed a comprehensive survey of Newfoundland from 1763 to 1767 it was a journey to the South Seas that would transform his fortunes. By the time of his return from Newfoundland, the Royal Society had been planning an expedition to the south Pacific to observe the transit of Venus across the face of the sun, which would enable the distance between the earth and the sun to be calculated. The Royal Society's first choice to lead this expedition was Alexander Dalrymple, but the Admiralty, who were to provide the ship, insisted that it should be commanded by a naval officer, and so Cook was appointed instead. The Whitby-built Earl of Pembroke of 336 tons was bought by the Admiralty and renamed Endeavour. Having passed for lieutenant on 13 May, Cook was appointed in command of her on 25 May 1768 and joined her two days later. The astronomer Charles Green was appointed by the Royal Society to observe the transit of Venus, with Cook as the second observer. Joseph Banks, a wealthy amateur botanist, also joined the expedition, bringing with him as his assistants Daniel Solander and Diedrich Sp'ring together with the landscape artist Alexander Buchan and the botanical artist Sydney Parkinson. The island of Tahiti, whose longitude had recently been determined astronomically by Samuel Wallis, was chosen for the observation. The Endeavour sailed from Plymouth on 25 August 1768 and, after calling at Madeira and Rio de Janeiro and rounding Cape Horn, anchored in Matavai Bay on the north coast of Tahiti on 13 April 1769. After successfully observing the transit on 3 June Cook, in accordance with his secret instructions, then sailed due south as far as 40'S to search for the great southern continent that geographers considered must exist in the Southern Ocean. Failing to sight land Cook then altered course to the west to investigate the land seen by Abel Tasman in 1642. The east coast of New Zealand was sighted on 6 October and Cook spent the next six months carrying out a running survey of New Zealand's North and South islands in which he established that Tasman's Staeten Landt was not part of the supposed southern continent. During this survey Cook was able to determine his longitude with considerable accuracy by means of the newly established method of lunar distances. Cook next carried out a running survey of the unknown east coast of Australia in which his discovery of Botany Bay was to have a significant effect on the history of that continent. During the survey Cook was forced to spend over six weeks in Endeavour River making temporary repairs after running aground on an isolated coral reef, now known as Endeavour Reef. He then made for Batavia (Jakarta) in the Dutch East Indies for more permanent repairs. In sailing through Endeavour Strait Cook confirmed the discovery of Luis Vaez de Torres in 1606 that Australia was not joined to New Guinea as shown on most maps. Before his final departure from Australia Cook took possession of the whole of the east coast of Australia in the name of George III, naming it New South Wales. After further calls at Table Bay and St Helena, Cook finally anchored in the Downs on 12 June 1771. Although thirty members of the ship's company and Banks's party, including both artists, died during the voyage, mainly as a result of illnesses contracted in Batavia, the voyage was judged a success and Cook was promoted to commander on 29 August 1771. In spite of the achievements of Cook's first voyage it was clear that there were vast areas in the Southern Ocean where a great land mass might yet be found. Cook therefore proposed that a search for it should be made by circumnavigating the globe from west to east in a high southern latitude, thereby taking advantage of the strong prevailing westerly winds to be found there. Cook's plan was accepted and two further Whitby-built vessels were purchased and named Resolution and Adventure, Cook being given command of the former and Tobias Furneaux command of the latter. As a result of disagreements Banks, who was to accompany the expedition, withdrew and his place was taken by the German-born scientist Johann Reinhold Forster and his son George, while William Hodges was engaged as the expedition's artist. An important secondary aim of the expedition was to give extended trials to a copy of John Harrison's prize-winning chronometer H4 made by Larcum Kendall, known as K1, and three others made to the design of John Arnold. To supervise these trials the board of longitude appointed two astronomers, William Wales to the Resolution to take charge of K1 and Arnold no. 3 and William Bayly to the Adventure to take charge of Arnold nos. 1 and 2. Cook sailed from Plymouth on 13 July 1772. After calling at Table Bay, where the Swedish botanist Anders Sparrman joined the expedition, he set a course to the south, and on encountering numerous tabular bergs, altered course to the east to begin his first ice-edge cruise. On 17 January 1773 he became the first person to cross the Antarctic circle. On 9 February, during an unsuccessful search in lower latitudes for land discovered by Kerguelen in 1772, the two ships became separated in a fog. When contact was not regained Cook decided to continue his sweep to the south before the onset of the southern winter, reaching Dusky Sound, in New Zealand's South Island on 27 March 1773, after a passage lasting four months without sighting land. He remained there for six weeks refreshing his crew and surveying this extensive inlet before joining Furneaux at the agreed rendezvous in Queen Charlotte Sound. On 7 June, with Furneaux in company, Cook got under way and after an uneventful passage anchored on 26 August in Matavai Bay. He then spent the next two months working his way back to Queen Charlotte Sound through the Society Islands and Tonga. Off the east coast of New Zealand's North Island the two ships were struck by a severe gale and on 30 October became separated for a second time. After waiting in vain for three weeks for Furneaux in Queen Charlotte Sound, Cook sailed on his second ice-edge cruise. On 26 January 1774 he crossed into the Antarctic circle for the third time (having done so a second time the previous month) and four days later, at 71'10' S, 106'54' W, achieved his farthest south. Cook now decided to spend one more winter in the south Pacific so that he could explore the south Atlantic the following summer. Making his way back to Tahiti, Cook anchored briefly off Easter Island, the first land to be sighted for 104 days. He next called at the Marquesas Islands before anchoring once more in Matavai Bay on 22 April. After spending a few weeks in the Society Islands Cook set off once again for Queen Charlotte Sound, visiting Tonga for a second time and carrying out running surveys of the New Hebrides (Vanuatu) and the north-eastern side of New Caledonia. In Queen Charlotte Sound he learned that Furneaux had arrived a few days after his departure and had sailed some days later. On 11 November Cook set off on the long voyage home, spending Christmas at anchor in the appropriately named Christmas Sound in Tierra del Fuego. After examining the north coast of Staten Island, Cook began his third ice-edge cruise, during which he rediscovered South Georgia on 14 January 1775 and discovered the South Sandwich Islands a few days later. Following an unsuccessful search for Bouvet's Cape Circumcision, Cook anchored in Table Bay on 21 March. After calling at St Helena, Ascension, and Fayal in the Azores, Cook dropped anchor in Spithead on 30 July after an absence of three years and eighteen days, during which four men had died, but only one from sickness and none from scurvy'a remarkable achievement. On his return to England Cook was promoted to post captain on 9 August 1775 and appointed fourth captain of Greenwich Hospital, an appointment he accepted with the proviso that it would not preclude him from being considered for further service. At first he was occupied with the publication of his journal under the general editorship of John Douglas, canon of Windsor, since the account of his first voyage by John Hawkesworth had been highly criticized. In March 1776 Cook was elected a fellow of the Royal Society and at the same time awarded the society's Copley medal for his work on the prevention of scurvy. Early in 1776 Cook came out of retirement to command a further expedition to the Pacific with the purpose 'that an attempt should be made to find out a Northern Passage by Sea from the Pacific to the Atlantic Ocean' (BL, Egerton MS 2177B). Once again he was appointed to the Resolution with the newly purchased Discovery, commanded by Charles Clerke, as consort. Cook and Lieutenant James King were to act as astronomers on board the Resolution, while William Bayly was appointed once more as the Discovery's astronomer. The artist John Webber, appointed to the Resolution, completed the scientific staff. Cook sailed from Plymouth once more on 12 July 1776, anchoring on 18 October in Table Bay, where he was joined by the Discovery. On crossing the Indian Ocean, Cook fixed the position of Prince Edward and Marion islands. He next carried out a running survey of the north coast of Kerguelen, establishing the island's longitude accurately with the aid of K1, which was once again carried on board the Resolution. After brief stops in Adventure Bay in Van Diemen's Land and his old anchorage in Queen Charlotte Sound, adverse winds forced Cook to call at Tonga instead of making directly for Tahiti. On eventually reaching the Society Islands, Omai, the Society Islander Furneaux had brought back to England, was landed at Raiatea. Cook then continued across the Pacific, making his first major 'discovery' on this voyage when Oahu and Kauai, at the western end of the Hawaiian Islands, were sighted on 18 January 1778. Next the north-west coast of North America was sighted on 7 March and for the next six and a half months Cook carried out a running survey of some 4000 miles of its coast from Cape Blanco on the coast of Oregon to Icy Cape on the north coast of Alaska, where he was forced to turn back by an impenetrable wall of ice. A search for a route back to Europe north of Siberia also proved fruitless. During this cruise Cook became the first European to enter Nootka Sound on the north-west coast of Vancouver Island, where he remained for a month taking astronomical observations and cutting spars for use as spare masts and yardarms. Trade was carried out with the native Mowachaht for furs, mostly of the sea otter, which when sold later in China drew attention to the commercial potential of this trade. Cook decided to winter in the Hawaiian Islands, which he had named after his patron the earl of Sandwich, before making a further attempt to find a north-west passage the following year. After carrying out a running survey of the easternmost of the Hawaiian Islands, Cook anchored in Kealakekua Bay on the island of Hawaii on 17 January 1779. At first he was well received and by some accounts was considered by the Hawaiians as the embodiment of their god Lono. On 4 February 1779 Cook got under way to continue his survey of the islands but was forced to return to Kealakekua Bay for repairs after the Resolution's foremast was damaged in a violent storm. It soon became clear that his return was not welcome, and bad relations culminated in the theft of the Discovery's cutter. On the morning of 14 February Cook, with less than his usual judgement, landed with an escort of marines in an attempt to persuade the local chief to return on board where he intended to hold him as a hostage against the return of the cutter. The chief readily agreed to accompany Cook, but at the landing place they were met by a hostile crowd and in the altercation that followed Cook and four of the marines were killed. Cook's body and those of the marines were carried away by the Hawaiians and, according to custom, were cut up and the flesh scraped from the bones and ceremonially burnt, the bones being distributed among the various chiefs. Clerke, who now took command of the expedition, eventually managed to persuade the Hawaiians to return the majority of Cook's bones. These were put into a coffin and, on the afternoon of 21 February, were committed to the waters of Kealakekua Bay. On 23 February the two ships put to sea to complete the survey of the Hawaiian Islands. Clerke then set a course for Petropavlovsk Bay in Kamchatka, from where he sailed once more for the Arctic in an unsuccessful attempt to complete Cook's instructions, in spite of the fact that he was dying of tuberculosis. Clerke died in sight of Kamchatka as the expedition was returning to Petropavlovsk and it was left to John Gore, who succeeded to the command, to bring the expedition safely back to England. Cook was survived by his wife but of their six children only three survived to young adulthood and none married so he left no descendants. His legacy lies in his contributions to exploration and science. In his three voyages to the Pacific, Cook disproved the existence of a great southern continent, completed the outlines of Australia and New Zealand, charted the Society Islands, the New Hebrides, New Caledonia, and the Hawaiian Islands, and depicted accurately for the first time the north-west coast of America, leaving no major discoveries for his successors. In addition the scientific discoveries in the fields of natural history and ethnology were considerable and the drawings made by the artists were of great significance. |

Empire in Your Backyard: Plymouth Article | Significant Individuals

Armed Forces | Art and Culture | Articles | Biographies | Colonies | Discussion | Glossary | Home | Library | Links | Map Room | Sources and Media | Science and Technology | Search | Student Zone | Timelines | TV & Film | Wargames