|

|

|

|

Sir Ralph Furse is recognized as ‘the father of the modern Colonial Service’. Before the First World War there was no unified colonial service and officers were appointed to individual colonial governments. In the 1920s it became evident that such an arrangement could not provide an attractive career, least of all in smaller territories. The Colonial Office conference of 1927 recommended the unification of all the territorial services and functional branches into a single HM colonial service. This was followed in 1929 by the appointment of a committee under Sir Warren Fisher, head of the civil service, to review the system of appointments. Despite its vulnerability to the charge of patronage, the committee endorsed Furse's recruitment procedures, supporting the Colonial Office preference for selection by references and interviews over the written examination required for the Indian Civil Service and the Colonial Office's eastern cadetships. However, to safeguard the principle of open competition, a colonial service appointments board was established, responsible to the civil service commissioners.

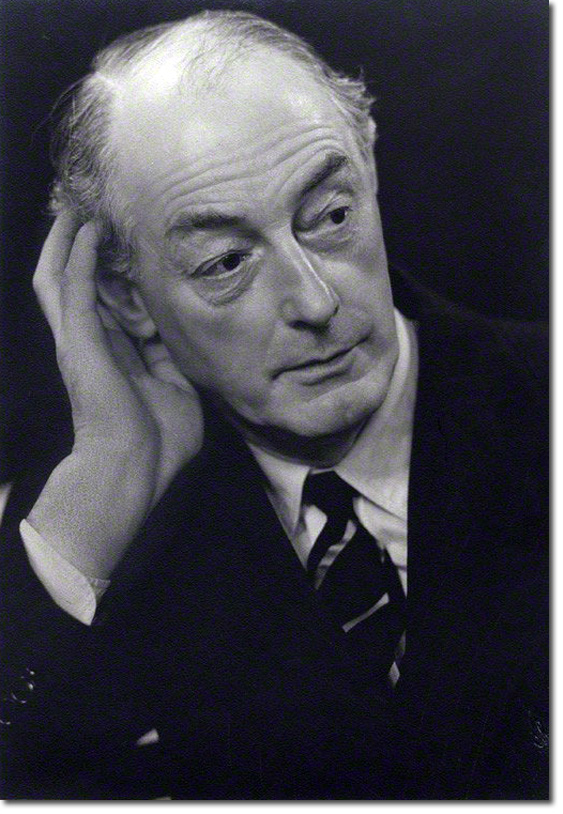

Furse was instrumental in opening up the colonial service to the dominions. As a result of visiting Canada in 1922 and Australia and New Zealand in 1928, the dominion selection scheme was initiated, with preliminary interviews of local candidates now taking place in their own country. In 1926 Furse persuaded Oxford and Cambridge (and later the London School of Economics) to organize training courses for cadets similar to those already operating for Indian Civil Service probationers. He was proud of his ‘recruiting spies’ among Oxbridge dons, notably Claude Elliott at Cambridge and H. Sumner, W. T. S. Stallybrass, Sir John Masterman, K. Bell, and P. A. Landon at Oxford. The master of Balliol, his own college, was at the bottom of his list of reliable referees. Again, Furse was the moving spirit behind plans for the post-war colonial service. His 1943 memorandum became a plank in the deliberations of the committee under the tenth duke of Devonshire, parliamentary under-secretary at the Colonial Office, and much of his thinking was incorporated into the new training programmes. Known as the Devonshire courses, they were essentially Furse's brainchild. Although Furse's greatest influence was on the formation of the colonial administrative service, his enthusiasm extended to the training of the agriculture, veterinary, and—in particular—the forest services. He was a member of the Lovat committee, from 1925 to 1928, on their professional training and was largely responsible for the founding of the Imperial Forestry Institute at Oxford, where his portrait now hangs. For a Colonial Office official he travelled unusually widely in the colonies. Furse was an intuitive judge of character, and with what a colleague called ‘his keen eye for men’ he chose his own staff—chief among them his brother-in-law and successor A. F. Newbolt—as unerringly as he selected his field officers. His aim was to raise the colonial service to the level of the Indian Civil Service among undergraduates seeking a crown career overseas. It was said that Furse's beau idéal of the colonial administrator was a man who had been a prefect at a public school and had captained a team at college: granted that such a personal triumph was but a floating distinction, it could also, Furse argued, be both a test and a presage of character. Another colleague recalled his charm and courtesy, ‘an ever fertile imagination and a forthright personality’. Colonial Office lore abounded of how Furse turned his increasing deafness to good account when the going became hard at meetings. The title of his autobiography, Aucuparius (1962), in which he expounded his uncannily successful and ebulliently subjective ‘hunches’, encapsulated the shrewd skill of the eponymous bird-catcher who netted birds of the highest quality. The chapter entitled ‘Our system’ is complemented by the in-house ‘Appointments handbook’, a confidential exposition of the Fursian code on the art of interviewing in search of what he roundly called the ‘spiritual’, with its focus on ‘the imponderables of character and personality’. One colonial service historian, an American (perhaps on safer ground reading Colonial Office files than grasping the nuances of the English class system), depicted Furse as ‘largely an unreconstructed Victorian country gentlemen. … his convictions about people socially are simple, straightforward and unshakable’, yet his admiration for the efficacy of the Furse system against the needs and conditions of the time is transparent: confident in his conception of the English gentleman, Furse brought the colonial service to ‘a peak of prestige’. In Lord Salisbury's opinion, Furse built up ‘by his own efforts and his own vision’ a recruitment system second to none. Furse spent his retirement on his family estate at Halsdon in Devon. A firm Christian, when in London he looked on St Michael Cornhill as his parish church. He died at the Withymead Nursing Home in Exeter on 1 October 1973. Picture Courtesy of National Portrait Gallery |

The Colonial Service Training Courses Article | Sir Richard Luce Address

Armed Forces | Art and Culture | Articles | Biographies | Colonies | Discussion | Glossary | Home | Library | Links | Map Room | Sources and Media | Science and Technology | Search | Student Zone | Timelines | TV & Film | Wargames