"A scenic heaven of which man had made a hell."

But nestled in her lusty beauty Africa's children have so often lived in terrible misery. Throughout her history African kingdoms prospered and then faded away before they could settle into civilisations. Trade would flourish; gold to the Pharoahs, ivory and spices to Europe, slaves to Egypt, Greece and Rome and, much later, to America. Powerful kings, chiefs and sheikhs rose out of the brief prosperity and their courts were pompous and splendid. Art flourished and many fine examples exist in museums and art galleries such as the wonderfully fashioned heads from Ife dating perhaps as far back as the 12th century and the famous and fabulous Benin bronzes made in the Sixteenth Century. But it seems that steady progress and prosperity was elusive and all too often the powerful chiefs and their people degenerated into depravity. The history of Africa, from what we can gather, was a rollercoaster of riches and famine, of peace and desperate tragedy. Many of Africa's people were cut off from the ebb and flow of learning by the continent's vastness. In most parts of sub-Saharan Africa before the latter part of the last century the wheel, currency and the written word were unknown. Travel was very limited and boats were small and frail, not designed for journeys but for fishing close to shore. The people were also badly weakened physically by malnutrition and animal borne diseases, some of which lodged in their bloodstreams for life. In East Africa, for example, they had to contend with malaria, sleeping sickness, black water fever, leprosy. yaws, intestinal parasites, dysentry, and bilharzia. (Leys) And in West Africa can be added to that list sickle cell, river blindness and the louse borne disease known as relapsing fever. Famine was a constant threat. Sir Frederick Jackson wrote: "My personal experiences of famines [In East Africa] were few, I am glad to say." and then he went on to mention one in 1863, "when, in the coast regions, children were sold into slavery by their parents." Another in 1896 in Kamassia where "of course, it was the women and children who suffered the most; they do so everytime, and the worst offenders in getting more than their fair share of the little food there were the young men of warrior age." And another in 1899 in Ukamaba, "a very bad and ever memorable one" where "the starving women and children were dreadful to look upon." It would be unreasonable to suppose that these famines were a phenomenon only of the Nineteenth Century. There is an interesting pointer to the physical damage caused by disease and malnutrition in a book written by my great aunt, Margaret Collyer, who went to Kenya in 1915. She refers to the small stature and weakness of the Kikuyu people (1) who could not be employed in heavy work such as road building. That was left to what were known then as the Kavirondo tribes who lived off the bounty of Lake Victoria. However, today the Kikuyu are tall, lithe, strong and competing successfully with the best of the best in the athletics field. Sleeping sickness alone wrought havoc in some populations. A species of tsetse fly is responsible for this disease which induces a hopeless and fatal torpor in a victim. In Uganda between 1901 and 1906 200,000 people died in an epidemic wiping out whole villages. (Miller) The tick and tsetse fly were also a constant menace to the domestic animals upon which the tribes relied. The mightiest tribe to hold sway in Kenya's rich grazing fiefdom which stretched over mountain and plain was the Masai. These nomads relied exclusively on the food produced by cattle, sheep and goats. Perhaps, it had happened before - perhaps many times - but in 1890 an epidemic of rinderpest swept through all of Africa. Nearly all the Masai cattle died. Many thousands of Masai died of starvation. Smallpox followed the rinderpest. Influenza followed the smallpox. Some believe that three quarters of the tribe died. Their old bitter adversaries, the Kikuyu and Kamba, seized their opportunity for revenge for the countless times the Masai had swooped upon their own villages. Their erstwhile conquerors were now reduced to "tattered bands" and the Kikuyu and Kamba often defeated them. Not only that, the Kikuyu and Kamba set upon defenceless manyattas (homesteads), killed the old and sold the young to Swahili traders, some were kept as Kikuyu and Kamba slaves. The Masai in turn retaliated, when they could, by wholesale massacres such as formerly they had never committed. (Leys) As if all these disasters were not enough for the African to contend with in his life, witchcraft and the occult dogged the daily lives of many villagers and made it problematical trying to get through each day. Cut off from the rest of the world generation after generation it is easy to see how fear of evil spirits could rule people's activities and also leave them open to exploitation by the more intelligent members of a community. For many it was a constant lottery to know when one had transgressed. It might be that their sin was as commonplace as stepping on a bone that had been chewed the night before. (Leys) But the witchdoctor was often all powerful and could bring his enemies to book without too much restraint. In some tribes there were trials for such misdemeanours but they could be grim. In Cameroun "trial by ordeal took place deep in the forest and the wretched wrongdoer was made to drink a deadly draught of poison concocted from powdered sasswood. If he or she vomited, acquital was declared but, of course, if the poison stayed down guilt and death followed." (Sharwood) Fear could often be used with impunity to keep people to heel. A description of this is given in Margaret Collyer's book where she describes a ghastly ceremony which took place on her farm in the early 1920's in order to discourage the petty thieving that plagued her early farming efforts. Her headman, Kago, first called a council which deliberated all day " when not a stroke of work was done." In the evening Miss Collyer handed over to them an old sheep. The ceremony, "whatever it was going to be, was to take place next day, when again no work would be done. It was all very sinister....." "The drumming that night being worse than usual, I could not sleep at all and went to Kago's tent to find out what it was all about, and whether I could witness the happenings on the morrow. At first he would not hear of my being present; no white man had ever been allowed at any of these ceremonies, and he evidently did not think it very safe. The sacrifice was to take place in the forest, where a clearing had already been prepared for it. On second thoughts Kago said I could go with him, but that we must both hide in a deep ditch near the spot, I being made to promise that, whatever I saw, I would not cry out or say a word to stop the proceedings... ...[That evening] it was eerie waiting in the gloom of the trees listening to the muffled beat of drums as the procession solemnly and slowly approached the forest edge. For a time it halted while the shrieking women were dismissed and the drums stilled. Now they came on again, marching silently; except for an occasional snapping of a dead stick, there was no sound to indicate that upwards of thirty men were within a short stone's throw of our sanctuary. So silently did they come that I was wondering what had happened to them, when the lamb and elders suddenly appeared and took the centre of the leaf-strewn stage. After these followed, in single file, the procession of Morans, who squatted in a circle round the three principle actors in this dramatic scene. How I wished I understood the Kikuyu tongue, for two long speeches were delivered by the elders, each in turn standing up during the course of his oration. ... For the next half hour I was forced to witness the most dreadful cruelty it has ever been my lot to imagine. The sheep was thrown on its side. One man pulled back the head, the other with a knife slit the skin between the bones from chin to joint of jaw, then drew the tongue down through the cut. Each warrior in turn was calledup, and on taking the oath bit off a portion of the living tongue. Then the legs of the animal were broken with sticks, each man repeating the following words (or as near as I can translate them) - 'As I break the bones of this sheep, so may I be broken if I steal while on this white woman's farm.' After having smashed all the sheep's legs to pieces, it was killed by cutting the throat." Cannibalism was another bloody cloud under which certainly some African men, women and children had to live. Sir Bryan Sharwood Smith, who was in the Nigerian Colonial Service, describes an evening in the twenties which he spent with the old men of North Eastern Cameroun, "their tongues loosened by the palm wine" they were drinking by the fire. "We were talking about the days when the ritual consumption of human flesh was a part of their daily life. As I displayed interest, the old men began to describe in grisly detail, exactly how these things had been arranged. The condemend were secured, head downward, between two upright stakes, their limbs spreadeagled. Beneath them burnt a slow, smokey fire. Around, in anticipation, squatted the elders, each with his back against an upright slab of rock in the position to which his status entitled him. As life passed, boiling palm oil was introduced into the body, from above - I had heard enough." It is understandable therefore that progress often faltered.

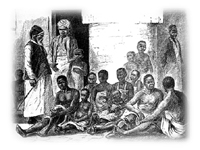

During the Nineteenth Century a great many, perhaps even the majority, of the ordinary men and women of Africa were so weakened and dispirited that many were wide open to violation. And violated they were by the 'Great African Catastrophe' of slavery. (Leys) Slave trading and slave taking was rampant throughout most of Africa. The European and Arab trade fed the markets of the desert potentates in the Horn of Africa. The slave trade fed the Romans and the Greeks for centuries and latterly the Americas and the Caribbean. Arab and Swahili slavers armed pugnacious tribes and encouraged them to prey upon the weak who would then be walked to the coast, shipped to Zanzibar and sold in the slave market. One such slaving chief, Mponda, who was also known as Mlozi (The Sorcerer) had his headquarters in what is southern Malawi today where the river Shire left lake Nyasa, and he commanded its exit with his guns. He called himself the Sultan of Nkonde but in fact he was a Swahili and he sucked the life blood out of the peaceful and prosperous Nkonde people. (Perham) Sitting in my comfortable chair I find it hard to imagine what it was like to walk mile upon thirsty, lonely mile with a heavy forked branch or gori stick fixed around my neck. But a record of a visit to an old slave halt in Kitale in Kenya in 1905, described by an old man who had served with Arab slavers brings home something of the stark reality. A Sudanese, Mbarak, worked for Captain Meinertzhagen in his old age and he took the Captain to visit the halt. "...a double stockade encircled an area of about 4 acres on a slight rise, with open ground for about 200 yards on all sides and a glorious view of Mt Elgon to the west and of the Cherangi hills to the East. Old Mbarak became quite excited when he found himself back in his old haunt and took me around the stockade, explaining what went on in every corner of the camp. The main gate was on the south of the stockade, the latter being made of solid wooden uprights woven together with thorn and smaller branches... Mbarak showed me where the Arabs slept near the entrance, where the girls were kept, where the boys were kept and where they were castrated, and where the men were kept constantly shackled in eights to a heavy log by iron chains. Castrated boys were best looked after as they were the most valuable but over fifty percent died before reaching the coast; the girls were not shackled but went free and were raped both at night and all through the day whenever the caravan halted."

"Carrying the mark of Cain. The harbour and its beach were studded with whatever bloated corpses or part-corpses might have escaped the attention of the sharks - affording 'sights' sufficient to shock even those who have been familiar with the dissecting-room. For murder was endemic on the island, and the harbour served as a convenient repository for the bodies of men, women and children who came to unwitnessed but grisly ends in the unlit alleys after night-fall. These unfortunates were usually the victims of lawless slave traders from Arabia and the Persian Gulf known locally as 'Northern Arabs' and dreaded by the townspeople. Not content merely with the human cargoes they could pick up in Zanzibar's open market, these slaves would scour the city at night, seizing anyone careless enough to go into the streets without an armed escort. Those who resisted got the blade of Jembia between the ribs and were pitched into the harbour. The submissive ones were bound and gagged, taken to caves along the shore and later transported secretly to the slave dhows." The Sultan of Zanzibar would have considered it a bad year if his annual income from duties on the slave traffic fell below on hundred thousand US dollars which is calculated at more than ten times that today. And it was, of course, the East African hinterland that was the source of such rich pickings. How men, women and children fell prey to the Swahili and Arab traders who captured and brought them to market in Zanzibar is told by one escapee to Frederick Jackson, one of the first Europeans to penetrate the area. Her name was Bahati (Fortune) and she came from what was then known as Ketosh around the north Easter spur of Lake Victoria known as the Kavirondo Gulf.

Her name was Bahati... (Fortune) It would appear that for many years past the Ketosh had been the happy hunting ground of the Swahili and Arab traders, particularly on those occasions when they arrived after an unsuccessful quest for ivory and with plenty of trade goods on hand; or when the easy acquisition of a batch of slaves was too tempting to forego. In either case, their tactics were the same... Having arrived at a village, and after accepting the proffered hospitality of a portion of [the population] the black-hearted ruffians would in due course announce that they required a large stock of food for their coastward journey, and that they were prepared to pay double the market price in order to obtain it quickly. The ruse, of course, attracted women and children from far and wide." Jackson explained that in the meantime, as a further blind, they told the villagers that it would be necessary for them to move camp outside the village and make a boma (stockade) in order to prevent the porters from running away on the day of their departure. The people came in to sell their produce on the appointed day and when they were all in the stockade, the gates were locked. "The women and children were seized and any man who offered resistance was shot. Old Bahati told us that that was the way she was taken captive." On the western side of Africa, Abeokuta was a market centre for a similar ocean going trade. To the north, in Zaria, there was yet another trade which was in Hausa and Fulani hands supplying the Mediterranean and the Middle East by way of the overland desert route. Witness to this in 1902 was a company of British soldiers, led by Captain Lugard, who were powerless to prevent "hundreds of slaves being hawked about in the streets in irons or a tribute of a hundred being sent off to Sokoto" (Perham) The girls were worth about five pounds and the boys were valued at six pounds. Sir Bryan Sharwood records that "The powerful chiefdoms in the Western Sudan - that vast belt of scrubland and savannah that stretched for hundreds of miles from Lake Chad - constantly preyed upon the weaker tribes. Many treated the border areas of their chiefdoms as no better than a breeding ground for slaves. Whole towns and villages were razed to the ground, the inhabitants being either slaughtered or carried into captivity." (Sharwood) The pagan tribes in the forest country north of the Niger suffered from the ravages of Umaru Nagwamatse, son of the fifth Sultan of Sokoto. District Commissioners in the first half of this century used to encounter, buried in the bush, the crumbling ruins of the town and villages that Umaru and his successor had pillaged in their search for slaves. These beleaguered people had to till their farms in fortified villages but were forced also to send tribute to Sokoto in an effort to ensure protection. It is odd but true that inter-tribal slave raiding seems to be more acceptable to us today as we beat our breasts over our own part in the intercontinental version. But it must have been no less terrible for the people involved. On the eastern side of Africa, which has no written history, it is difficult to know exactly the scale of inter-tribal slave raiding. But, in 1933, my father served in the northern desert known as NFD [Northern Frontier District]. His Handing Over Report describes at length the nine tribes which either wandered through his bailliewick or portions of which inhabited the area. One tribe was the Gurreh, a mainly light-skinned people who were strict Muslims and now roamed between "Abyssinia and British Territory." Another tribe, The Gurre Murre, were: "an agricultural tribe of negroid origin, the greater number of whom are resident in Abyssinia or Italian Somaliland. They were at one time slaves of the Gurreh." (My emphasis in bold.)(2) Perhaps some quiet corners of Africa were free from slavery and life for the people was the idyll of peaceful prosperity that many people nostalgically imagine the whole of Africa to have been. But the picture does not suggest this. Whisking ourselves north of Kenya's NFD to the Sudan, life for the average man and woman throughout history must have been at best tough but often desperate. General Gordon described it as "a useless possession, ever was so and ever will be so. Larger than Germany, France and Spain together, and mostly barren it cannot be governed except by a dictator who may be good or bad... No one who has ever lived in the Sudan can escape the reflection on what a useless possession is this land. Few men also can stand its fearful monotony and deadly climate." Allan MacCall, a one time Director of Agriculture in the Sudan, wrote: "Before the outbreak of the Mahdi's rebellion in 1881, the total population was calculated as having been 8,500,000 [in a country of 1,000,000 square miles, the largest country in Africa]. Of these, some 3,500,000 were killed by famine and disease, and some 3,250,000 in battle and tribal strife between 1882 and 1898.(3) In about 1822, when Muhammed Ali, an Albanian employed by the Sultan of Turkey, fought his way to supreme power as 'Pasha of Egypt', he needed money and slaves. He decided to invade the Sudan. By the middle of the century, he was more or less in control of the country. However, government was chaotic and predatory. In 1839 the number of slaves led away into captivity was at least 200,000. Conditions were appalling. By 1869 the power of the slave traders became so great that they were practically independent kinglets, with armed forces at their call, flouting the authority of Khartoum. This was a state of affairs that Ismail Pasha, who had become Khedive of Egypt in 1863, could not brook, and a policy of reform was initiated. On this occasion the agents were Europeans and their efforts were genuine. What these few British, Swiss, Austrians, Italians, Cand and others could do, they did. However, the vast distances, difficulties of communications, the climatc conditions, the general confusion prevailing and, above all, the calculated obstructiveness of a venal official staff, rendered their task a hopeless one. Today, as Civil War and strife still impinges upon the people of the region, we may reflect that life under the British Flag was not all bad. Indeed, it may be said by some that it was a golden age for those tragic peoples. Slavery of any kind was certainly an opportunity for the powerful to get rich quick. The European slaving ships were particularly active along the West African coast and there are families in Europe and Africa today whose fortunes are based on the slave trade. However, in Britain attitudes began to change. Sir Thomas Fowell Buxton, a vigorous and prominent anti-slavery campaigner, wrote "The Bible and the plough must regenerate Africa." while Lugard, who was later to become the founder of the Colonial Service in Africa said, "We have thus a duty of expiation to perform towards the Africa." and he believed that "I can think of no juster cause in which a soldier can draw his sword" than to fight slavery. The abolition movement achieved succes in 1807 with the Abolition of Slavery Act which made it a felony for any British ship to engage in the 'carrying trade'. From that date the West coast of Africa was patrolled by the Royal Navy. Known as the coffin squadron, these ships and their crews faced determined opposition. Skirmishes at sea and diseases from the land took a heavy toll and the valiant contribution of those naval crews to peaceful trade has been all but forgotten. Lagos was the last major stronghold of slavers which was captured by the Royal Navy in 1851. (Sharwood Smith), However, there were domestic slaves in Africa right into the 1920's and some District Commissioners had the task of giving them their freedom when they asked for it. In Eastern Kordofan in The Sudan, when a slave petitioned to be free he was either sent to special villages designated to freed slaves or an effort was made to reconcile him with his master - who often very much depended upon him to water his flocks and herds - on the basis of a free servant. (Henderson) Poor beautiful Africa. Distance and difficult terrain kept her out of the currents of knowledge, diseases weakened her people, famine depopulated her, fear of the supernatural hobbled so many of her tribes and slavery created a massive brain drain. In the Nineteenth Century, communications in Europe and the Americas improved apace. By the second half of the century, it was a natural progression that Europeans would be reaching Africa and striking inland. During this period there was in Northern Europe what some described as a mini-ice age when extreme cold caused great hardship and famine. One August in Scotland, farmers were walking on ice above the standing wheat fields. (Dixon) Perhaps this acted as a spur but, whatever the reasons, many headed for Africa. Some among them were men with avarice and power on their mind. "The adventurers and speculators into whose hands Africa would fall if the great governments abandoned the continent." wrote Dr. Leys. In 1903 a man called Gibbons, together with 30 armed Swahilis, had installed himself in an area south east of Mount Kenya where he had hoisted the union flag. He was busy collecting hut tax and extorting ivory and fourteen year old girls from the local population. The colonial government charged him and packed him home in chains. (Meinertzhagen)

A major Kikuyu chief called Karurie had much of his vast wealth - he lived in splendour with 39 wives and 60 children - lifted off him by a certain Bryce who offered to take his store of ivory to the coast to sell. That was the last time the chief saw the ivory or Bryce.

It would be inaccurate and unfair to put down the British colonial enterprise solely to exploitation and aggrandizement. Morris tells us in her book 'Pax Britannica' that "The Dualla chiefs of the Cameroons repeatedly asked to be annexed, but the British either declined or took no notice at all."

Lord Lugard can be accurately described as the father of the British Colonial Service in Africa. His biographer, Margery Perham, also made it her life's work to study the British Colonial Service. She accuses early British Governments of being more interested in spheres of influence in Africa than annexation. She cites the example of the country then known as Nyasa but which is Malawi today. The Swahili and Arab slavers in this area were extremely powerful and some of the British traders wanted then newly arrived Captain Lugard to lead an expedition to take them on. However, the Prime Minister, Lord Salisbury "would neither send an expedition to Nyasa, nor annex it, nor declare it British territory." He went so far as to say "We cannot begin a crusade into the interior."

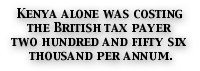

The cost of colonialism was no snip. Less than a decade after the Union Jack had been run up over East Africa, Sir Charles, Eliot told Lord Delamere that Kenya alone was costing the British tax payer two hundred and fifty six thousand per annum. And there were ten other major colonies to finance.

These sons of Britain were not blimps sporting large moustaches, carrying bullwhips in one hand and gin and tonics in the other as portrayed by the makers of modern faction. They were graduates from the finest British universities or survivors of distinguished military service.

Many of them were keen sportsmen. Indeed, the Sudan Political Service had the reputation of accepting only double blues. However, there was also a fair sprinkling of the small, the tubby and the bespectacled. But, with few exceptions, they arrived equipped with an independent spirit, courage, ingenuity, and unimpeachable integrity.

Many of the young men who went out to Africa were from families with a reasonably solid financial base. However, this does not mean that they did not need to be in paid employment and nor were they fops or lay-abouts only bent upon the pursuit of pleasure.

My father, Hal Williams, whose family did not have money [he had won a scholarship to Cambridge] joined the Kenya Administration in 1931. He wrote that he had "looked forward to the opportunity of doing some good amongst backward peoples." He also liked to tease us by saying that his main motive was to get away from his creditors. There may have been some truth in this because, anxious about being pursued by "an august body called the Colonial Service Debt Collecting Agency" he earnestly hoped that his first posting would be in the "blue, blue, blue" where the cost of living would be cheap ne could repay his university debts.

Whatever the personal reasons for joining the colonial service and whatever their triumphs, tragedies or achievements, they were there to serve and they knew it. Their job was to create an atmosphere where trade and ideas would prosper and where the people could take the necessary step into the modern world in a benevolent and secure environment.

Lord Lugard, who drew up the tenets for the British Colonial Service, said that the DC's role was to "maintain and develop all that is best in the indigenous methods and institutions of native rule." (Perham) The people of Africa under British rule were regarded as "wards in trust" which may today appear paternalistic and patronising but it was a serious responsibility. Part of a Governor's oath in The Sudan was to do "right by all manner of men, without fear or favour, affection or ill-will." (Davies)

These pages are the story of those British men and their wives who many times have been pilloried by the historians and intellectuals who were never there. Their worst failing was snobbism which prevailed all over the world at the time. This has now been interpreted as racism which it certainly was not. They simply did their honest and absolute best within the understanding of the time and their achievements are staggering.

In less than three score years and ten, they lifted broken, disprited and depraved Africa into a new plane of knowledge, security and prosperous trade.

Despite two world wars and the worst world depression ever known, they rushed her people through a crash course in living in the modern age and then handed them the keys to their bountiful and ravishing land.

"In 1880" wrote C. R. Niven in 1946 while serving in Nigeria, "a man or woman would not have dreamed of walking alone, say, the fifty miles between Kabba and Lakoja [In Nigeria]; thirty years later, in a single generation, no one would have thought twice about it. As the Hausa says, 'a virgin [can now] carry a calabash of eggs from Kano to Sokoto [250 miles] and neither would be spoilt on the way."

|

|

|

|

| Frederick Lugard | Charles Gordon | Arthur Collyer |

Back to Table of Contents | Back to Articles | Chapter 2

Armed Forces | Art and Culture | Articles | Biographies | Colonies | Discussion | Glossary | Home | Library | Links | Map Room | Sources and Media | Science and Technology | Search | Student Zone | Timelines | TV & Film | Wargames