|

|

|

|

Born in 1823, he was first employed in a silk warehouse and afterwards in the office of a merchant engaged in the Eastern trade. In 1847 he went out to India and joined his old schoolfellow Robert Mackenzie, who was engaged in the coasting trade in the Bay of Bengal. Together they founded the firm of Mackinnon, Mackenzie & Co.

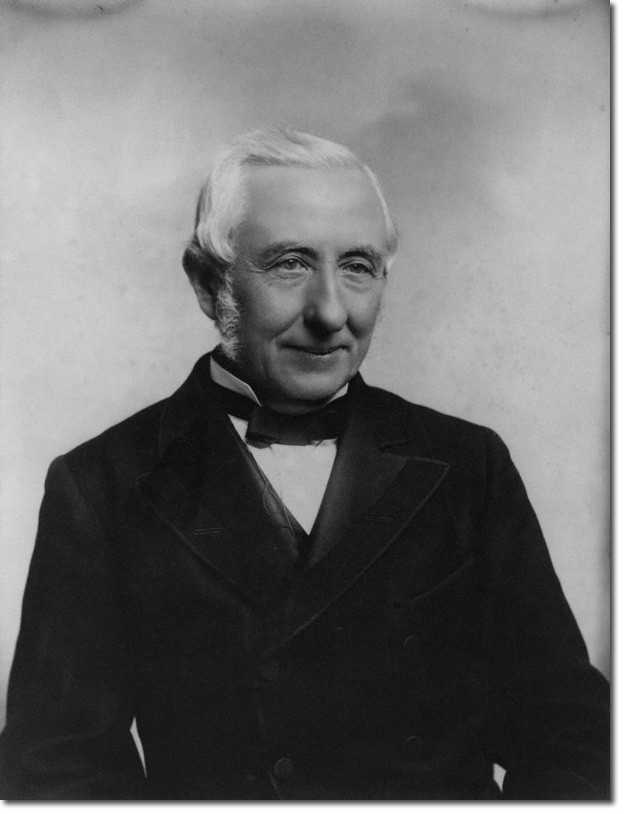

On 29 September 1856 the Calcutta and Burmah Steam Navigation Company was founded mainly through Mackinnon's efforts. It was renamed the British India Steam Navigation Company on 8 December 1862. The company began with a single steamer plying between Calcutta and Rangoon, but under Mackinnon's direction it became one of the greatest shipping companies in the world, developing, and in many instances creating, a vast trade around the coast of India and Burma, the Persian Gulf, and the east coast of Africa, besides establishing subsidiary lines of connection with Britain, the Dutch East Indies, and Australia. He was careful to have his ships constructed in such a manner that they could be used for the transport of troops, thus relieving the Indian government from the necessity of maintaining a large transport fleet and ensuring employment for his vessels. His great business capacity did not override the humanity of his disposition: on learning that during a famine in Orissa his agents had made a contract with the government for the conveyance of rice from Burma at enhanced rates, he at once cancelled the agreement, and ordered that the rice should be carried at less than the ordinary price. About 1873 the company established a mail service between Aden and Zanzibar. Mackinnon gained the confidence of the sultan, Seyyid Barghash, and in 1878 he opened negotiations with him for the lease of a territory extending 1150 miles along the coastline from Tungi to Warsheik, and extending inland as far as the eastern province of the Congo Free State. The district comprised at least 590,000 square miles, and included lakes Nyasa, Tanganyika, and Victoria Nyanza. The British government, however, declined to sanction the concession, which, if ratified, would have secured for Britain the whole of what became German East Africa. In 1886 Lord Salisbury, the foreign minister, used Mackinnon's influence to secure the coastline from Wanga to Kipini as a British sphere of influence, but declined to become directly involved in east Africa. Mackinnon formed the British East Africa Association, to promote the formation of a company; 250,000 pounds was subscribed. A charter was granted, and the Imperial British East Africa Company was formally incorporated on 18 April 1888, with Mackinnon, who had subscribed 10 per cent of the shares, as chairman. The company acquired a coastline of 150 miles, including the excellent harbour of Mombasa, and extending from the River Tana to the frontier of the German protectorate. The company, which included among its principles the abolition of the slave trade, the prohibition of trade monopoly, and the equal treatment of all nationalities--and among its subscribers Sir Thomas Fowell Buxton and the husband of Angela Burdett-Coutts--found itself seriously handicapped in its relations with foreign associations, such as the German East African Company, by the strenuous support which they received from their respective governments. The British government, on the other hand, was debarred by the principles of English colonial administration from offering similar assistance. The territory of the company was finally taken over by the British government on 1 July 1895 in return for a cash payment. Mackinnon had a great part in promoting Sir H. M. Stanley's expedition for the relief of Emin Pasha. In November 1886 he addressed a letter, urging immediate action, to Sir James Fergusson, under-secretary of state for foreign affairs, and followed this by submitting to Lord Iddesleigh, the foreign secretary, a memorandum suggesting the formation of a small committee to send out an expedition. He and his friends subscribed more than half the sum of 29,000 pounds provided for the venture, the rest being provided by the Egyptian government. Mackinnon had contacts with Leopold, king of the Belgians. When, however, the awful condition of African forced labour in the Congo became known--the 'red rubber' scandal--Mackinnon became a prominent member of the anti-slavery campaign. Mackinnon was for some time a director of the City of Glasgow Bank, and assisted in extricating the concern from its earlier difficulties. In 1870, finding that he could not approve the policy of the other directors, he resigned his seat on the board. On the failure of the bank in 1878 the liquidators brought a claim against him in the Court of Session for about 400,000 pounds. After protracted litigation Mackinnon, who had peremptorily declined to listen to any suggestion of compromise, was completely exonerated by the court from the charges brought against him, and it was demonstrated that the course taken by the directors was contrary to his express advice. Mackinnon was an active supporter of the Free Church of Scotland. Towards the end of his life, however, the passage of the Declaratory Act, of which he disapproved, led to some difference of opinion between him and the leaders of the church, and he materially assisted the seceding members in the Scottish highlands. In 1891 he founded the East African Scottish Mission. In 1882 Mackinnon was nominated CIE, and on 15 July 1889 he was created a baronet. He died in London, in the Burlington Hotel, on 22 June 1893, leaving an estate worth more than half a million pounds. He was buried at Clachan in Argyll on 28 June. The baronetcy became extinct with his death. Mackinnon possessed great administrative ability. When Sir Bartle Frere sent Sir Lewis Pelly to the Persian Gulf in 1862 he said, 'Look out for a little Scotsman called Mackinnon; you will find him the mainspring of all the British enterprise there.' A bronze statue by Charles McBride of Edinburgh was unveiled in Treasury Gardens, Mombasa, in 1900; after Kenya's independence it was moved first to Keil School, Kirktonhill, and then, after the closure of that school, to Kinloch Street, Campbeltown. Image courtesy of National Portrait Gallery |

Armed Forces | Art and Culture | Articles | Biographies | Colonies | Discussion | Glossary | Home | Library | Links | Map Room | Sources and Media | Science and Technology | Search | Student Zone | Timelines | TV and Film