|

|

|

|

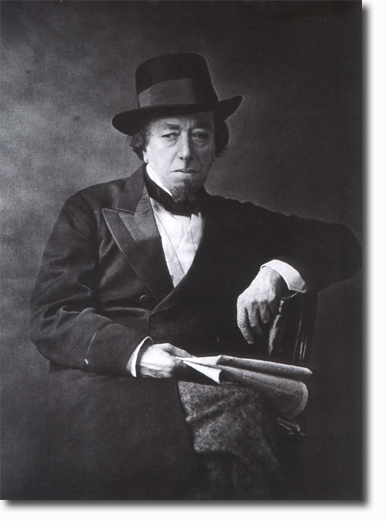

Disraeli would do battle with the mighty Gladstone for much of the second half of the Nineteenth Century. Between the two of them, they would come to epitomise the Westminster parliamentary political system. They were both unlikely in their way, but Disraeli's rise to the top of the 'greasy pole', as he termed it, was probably the most unlikely. Born to a Jewish Italian writer, the fact that he would rise to the head of the party of privilege and lead it in surprising directions.

He was originally elected as a Peelite Conservative but Sir Robert Peel was to ignore his keen Young Turk which was to disappoint Disraeli. He sought solace with the creation of the Young England group in 1842. Disraeli and members of his group argued that the middle class now had too much political power and advocated an alliance between the aristocracy and the working classes. Disraeli suggested that the aristocracy should use their power to help protect the poor. This political philosophy was expressed in Disraeli's novels Coningsby (1844), Sybil (1845) and Tancred (1847). but would come to attack his leader over the issue of the Corn Laws and would vote against him to bring about the fall of his own government. In 1852, Lord Derby offered Disraeli a place in government as Leader of the Commons and Chancellor of the Exchequer. However, he did not get off to a good start as his budget was torn to pieces by Gladstone and caused the government's downfall. Palmerston and his liberals would keep the Conservatives out of power for much of the next decade and more. It was not to be until 1866 that Disraeli came to return to the cabinet as Chancellor of the Exchequer and leader of the House of Commons. To the surprise of many, particularly Tories, he would champion a surprisingly liberal extension of the franchise. His 1867 Reform Act would give th vote to all male householders in the boroughs and to those paying ten pounds or more in lodging or rent. His gamble in enfranchising one and a half million men would not pay off immediately as the Conservatives lost to Gladstone's Liberals. However, Disraeli's appeal to working class nationalism would gradually bring converts to the Conservatives and they would win their first clear majority in 1874 since Peel in 1841. Disraeli's progressive form of Conservatism would be implemented energetically over the next six years. Social reforms passed included: the Artisans Dwellings Act (1875), the Public Health Act (1875), the Pure Food and Drugs Act (1875), the Climbing Boys Act (1875), the Education Act (1876). He also introduced measures to protect workers like the 1874 Factory Act and the Climbing Boys Act (1875). Disraeli kept his promise to improve the legal position of trade unions by introducing the Conspiracy and Protection of Property Act (1875) which allowed peaceful picketing and the Employers and Workmen Act (1878) which enabled workers to sue employers in the civil courts if they broke legally agreed contracts. Disraeli built up a particularly good working relationship with Queen Victoria. She approved of Disraeli's imperialist views and his desire to make Britain the most powerful nation in the world. In 1876 Victoria agreed to his suggestion that she should accept the title of Empress of India. In August 1876 Queen Victoria granted Disraeli the title Lord Beaconsfield. Disraeli now left the House of Commons but continued as Prime Minister and now used the House of Lords to explain his government's policies. At the Congress of Berlin in 1878 Disraeli gained diplomatic success in limiting Russia's power in the Balkans although there was widespread revulsion at Turkish atrocities a theme that Gladstone would later exploit. His way of keeping 'Tories' on side with his more progressive reforms was to appeal to their imperialist and nationalist ambitions. However, this was easier said than done. A series of high profile military disasters in the colonies would badly undermine his popularity within the party and the country at large. Disasters at Isandlwana by the Zulus in Southern Africa and at Maiwand in Afghanistan would undermine his imperial credentials and would help lead to his defeat by Gladstone in the 1880 general election. Disraeli decided to retire from politics. Disraeli hoped to spend his retirement writing novels but soon after the publication of Endymion (1880) he became very ill. Benjamin Disraeli died on 19th April, 1881. Shortly after his death, the 'Primrose League' was established to try and continue his particular brand of nationalist Toryism. The Primrose being Disraeli's favourite flower. The Primrose League's pledge shows its imperial ambitions: 'I declare on my honour and faith that I will devote my best ability to the maintenance of religion, of the estates of the realm, and of the imperial ascendancy of the British Empire; and that, consistently with my allegiance to the sovereign of these realms, I will promote with discretion and fidelity the above objects, being those of the Primrose League' It was particularly strong in the heyday of empire in the 1890s but after the Boer War it began to slip in popularity. It was finally wound up in 2004 when the lack of empire made it redundant. |

|

Disraeli A six hour mini-series from 1978 that tells how Disraeli rose to the top of the 'greasy pole' against all the political odds.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Armed Forces | Art and Culture | Articles | Biographies | Colonies | Discussion | Glossary | Home | Library | Links | Map Room | Sources and Media | Science and Technology | Search | Student Zone | Timelines | TV & Film | Wargames