|

|

|

|

Having last seen service at Waterloo, Elphinstone was hoping to run down his career gently in Bengal. However, he was suddenly uprooted by the governor-general, Lord Auckland, to succeed General Willoughby Cotton in command of the British troops in Kabul. Despite his protest that he was unfit physically for such an active command, he was overruled; suffering from gout, he had to make most of the journey from Calcutta to Kabul in a palanquin.

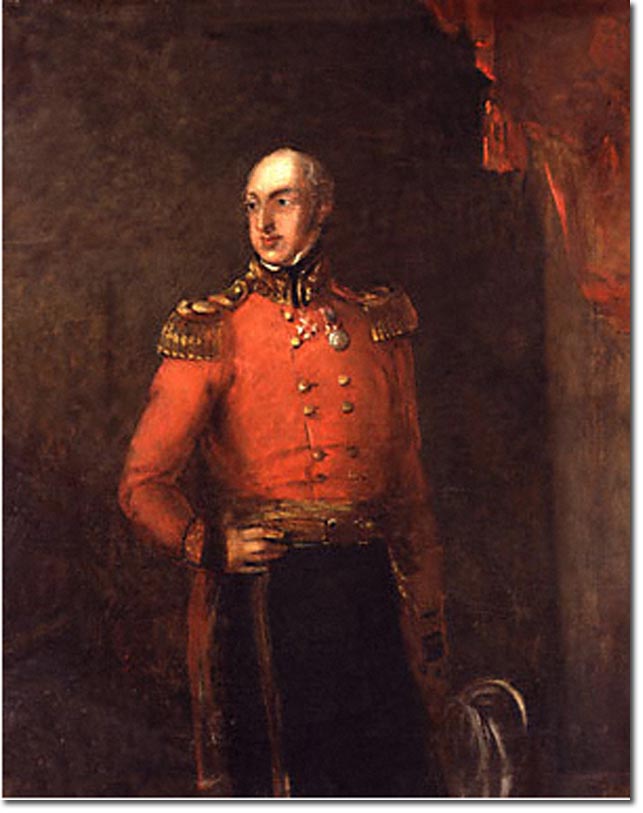

By late 1840 the war in Afghanistan was apparently over. Dost Muhammad had surrendered and abandoned the throne to Shah Shuja, the British nominee. The major part of the British invasion army had returned to India, leaving only garrisons in Kabul and Kandahar to support Shah Shuja, and the British resident, Sir William Macnaghten. When Elphinstone arrived in Kabul the situation seemed calm enough for wives and children to come from India to Kabul, where the garrison was enjoying as normal a peacetime existence as in an Indian cantonment. However Sir William Macnaghten and his principal assistant, Sir Alexander Burnes, had misjudged the political situation. The Afghan chiefs were opposed to Shah Shuja and resented the British occupation. Even Elphinstone, who reached Kabul exhausted, mentally and physically, queried the defensibility of the British cantonment at Sherpur, outside Kabul, but any attempt at improvement was turned down on the grounds of expense. 'Unfit for it, done up body and mind' (Macrory, 47) is how Elphinstone described himself to Major George Broadfoot in October 1841. He intended to ask for relief on medical grounds. Incapable through pain and debility of making up his mind, he held repeated conferences, soliciting the opinion of even the most junior of those attending, but never reaching a conclusion. He was little helped to do so by his second in command, Brigadier John Shelton of the 44th foot, who openly despised him. Elphinstone was utterly unfitted to cope with the increasingly grave situation following the Kabul insurrection of 2 November and the assassination of Sir William Macnaghten by Akbar Khan, a son of Dost Muhammad, on 23 December 1841. The Afghans closed communication with Kabul and besieged the cantonment. Against his better judgement Major Eldred Pottinger, himself wounded, as the senior remaining political officer, was ordered to negotiate with Akbar Khan for the safe return of the Kabul garrison to India at the height of the Afghan winter. The terms were humiliating, the Afghan guarantees worthless, and subsequently almost the entire garrison was destroyed in the passes between 6 and 13 January 1842. Some nineteen officers and ten wives with their children were taken into Afghan captivity, some as hostages, Elphinstone among them. He was wounded at Jagdalak during the retreat on 12 January. The prisoners were mostly not treated badly, but Elphinstone, racked with dysentery, had lost the will to live. He died unmarried, on the night of 23 April at Zanduk, near Tezin. Akbar Khan arranged for the body to be taken to Jalalabad, then British-held, and there Elphinstone was buried with military honours on 30 April; his grave is unmarked. Colin Mackenzie and other Anglo-Afghan war survivors later paid tribute to his personal qualities: he was well-meaning and kindly--though inadequate for command. In the immediate aftermath of the Afghanistan disaster Elphinstone was much blamed, but the true blame lay with Lord Auckland and his adviser Sir William Macnaghten for undertaking the invasion of Afghanistan and for choosing a sick, disabled, and prematurely aged general, who had not served in battle since Waterloo, to command in Kabul. |

First Afghan War | Significant Individuals

Armed Forces | Art and Culture | Articles | Biographies | Colonies | Discussion | Glossary | Home | Library | Links | Map Room | Sources and Media | Science and Technology | Search | Student Zone | Timelines | TV & Film | Wargames