| The New World | |

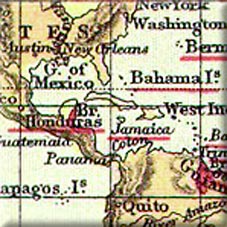

The Portuguese journeys to the Orient in the late Fifteenth Century had inspired Europeans to look for an alternate route to the riches and spices of the East. The Spanish had been the first European rival to find a route travelling westwards. The fact that the Americas lay in between Europe and Asia by this route was an added complication. Eventually a southern route around the Cape Horn was discovered, but it was so treacherous and arduous that it was not really a viable option for the frail ships of the Sixteenth Century. Undaunted, the Spanish discovered an alternate route that was developed over time. The narrowness of the Panama Isthmus meant that the Spanish could travel across Central America to the Pacific Coast and build ships and port facilities on that western coast. The portage required combined with the fact that the Pacific Ocean was far larger than original calculations had anticipated meant that it was not a viable alternative route to the Orient, but it did give the Spanish strategic and trading options. Fortunately for the Spanish they were able to locate silver and agricultural products that were to help make South and Central America profitable in their own right. The wealth of the New World began filtering back to Spain and helped fund its own naval and political expansion in Europe.

A potential clash with rival Catholic power Portugal was averted by the intervention of the Pope and the Treaty of Tordesillas in 1494 which effectively assigned Spain control of most of the New World and Portugal the Orient via the African route. There were two important exceptions which were that parts of Brazil protruded further than the Treaty had anticipated and so lay in the Portuguese zone, and the Philippines were assigned to Spain as long as they came via the Pacific route. So each Catholic power had a foothold in the trading territory of their rival.

Other European maritime nations, like England, were becoming increasingly interested in the source of wealth for these Iberian powers and began to send expeditions and reconnaissance voyages of their own.

| | The Spanish Period | |

The Spanish technically had the vast American continent to themselves - although its size dwarfed the resources even of the Spanish to successfully police and defend their settlements and claims in entirety over the coming centuries. However, the Spanish certainly received a healthy head start in exploring, conquering and expropriating the resources of the continent to their own advantage. For much of the Sixteenth Century, they were barely challenged as the only possible rivals, Portugal, were generally content with their own trading opportunities in Asia.

After exploring the Caribbean extensively enough to confirm that there was no sea route to the Pacific, the principal interest of the Spanish was to move away from the Caribbean Islands to the Spanish Main (as South America was then called). The Spanish Conquistadores were motivated by the quest for money and particularly gold. There were a number of established empires on the mainland that could be confronted and whose possessions and lands could be seized. Additionally, the legend of El Dorado quickly took prominence and repeated fruitless searches for the mythical city of gold were undertaken by Spanish adventurers and noblemen seeking their fame and fortune. However, it was not to be gold that made Spain's fortune in South America but 'silver'. The Spanish seizure of the silver mines of Potosi in the Viceroyalty of Peru (although now in modern day Bolivia) was a world changing event. The sheer quantity and quality of silver discovered transformed the Spanish economy and turned the Spanish Main into a veritable cash cow for the Spanish Crown. Its principal drawback was the fact that it was located closer to the Pacific coastline than the Atlantic one. This meant that the extracted silver had to make a journey to La Paz and then on to Lima via Cuzco where it was boarded on a ship. It was then transported to Panama where it had to be unloaded and taken by land across the isthmus to Nombre de Dios where it was reloaded on to ships to take back to Spain on the so-called 'Treasure Fleets'. So, although the Caribbean was not the creator of this vast amount of wealth, it provided a vital conduit to allow the silver to reach Europe. Of course, some of that wealth was also used in and around the Spanish settlements to provide defence and investment for other economic activities in the region.

| | The Tudor Challenge: Pirates of the Caribbean | |

With Portugal's primacy along the African route to the Orient, and the Spanish primacy in the Western Hemisphere, the English searched forlornly for a North-Easterly or a North-Westerly route to the riches of Asia. Both of these foundered in the harsh Arctic seas, but their search for a North-Western route did at least bring them into contact with the Americas if a lot further North than where the Spanish were located. Westcountry fishermen in particular began to undertake voyages across the Atlantic to fish the plentiful fishing grounds off Newfoundland. Slowly English mariners acquired the skills and knowledge to become proficient at long and arduous oceanic voyages.

In fact, it was a West Country mariner who first attempted to muscle his way into the Spanish controlled Caribbean. John Hawkins from Plymouth undertook a series of voyages to take slaves from Africa to the Spanish colonies of the Caribbean where he hoped to sell them at a profit. His first voyage was indeed relatively successful when isolated Spanish administrators turned a blind eye to the illegal importation of much needed slaves by this English interloper. However, when the Spanish government learned of what had happened they attempted to reassert control and prohibited their officials from trading again with this Protestant English mariner. Three subsequent voyages offered diminishing returns with his last voyage ending in disaster when a Spanish fleet attacked and destroyed much of Hawkins' small fleet at San Juan de Ulua in 1568. It was clear that the Spanish were determined to defend their monopoly rights to the New World.

All this time, the Treasure Fleets continued their sailings across the Atlantic. The arduous journey injected vast amounts of money into the European economy. Spain was able to use its new found fortune to wage sustained wars against the rising Protestant powers as the Reformation threw up new religious complications on the continent. The sheer quantity of silver also ignited inflation throughout Europe as prices rose due to the infusion of coinage into economies not used to so much high quality precious metal swirling around its population. It also inflamed envy as the Protestant nations in particular sought to disrupt the flow of money to Catholic Spain or better yet to expropriate the silver for their own use. Huguenot French, the Dutch and the English all came into this category as their sailors slowly acquired the skills and technology to match and challenge the Spanish navy. One of the most famous of these sailors, a nephew of John Hawkins, had been present at the San Juan de Ulua debacle and had vowed personal revenge on Catholic Spain. The Spanish referred to him as 'El Draco' but his real name was Francis Drake.

Drake sailed to the Caribbean a number of times in the 1570s and was the first Englishman to set eyes on the Pacific Ocean whilst attempting to reconnoitre the overland trans-shipment routes for the Spanish treasure ships (which he successfully captured at Nombre de Dios in 1573). Both he and the Spanish appreciated that the isolation of the Pacific from the Caribbean was both a blessing and a curse. For the Spanish, it afforded peace of mind as they regarded the Pacific as their own Spanish lake. They had also established a base in the Philippines which allowed some of the trade of the Orient to also be trans-shipped via Panama. The difficulties and complexity of portaging goods across Central America was perhaps a small cost to pay. For the English, the isolation made it very difficult to get to the Pacific but it had the compensating factor that the Spanish felt safe and secure and did little to protect their ports and ships on the Pacific coastline. Drake was to take advantage of this over-confidence during his 1577 - 1580 circumnavigation of the World when he sailed through the difficult channels of Tierra del Fuego and made it to the Pacific.

Technically, England and Spain were at peace, but the concept of 'No peace beyond the line' meant that the long distances and isolated outposts of the Caribbean and the Western Hemisphere were beyond the realms of diplomatic niceties and European agreements. The original phrase derived from the French and Spanish whose arguments in the Caribbean were as great as between the English and Spanish. They agreed on a notional line in the Atlantic Ocean beyond which accepted European treaties would not apply. The English, in treaties in 1604 and 1630 formally recognised this same principle. What events happened in the colonies and the high seas were regarded as fair game. In this vain, Drake happily raided the Spanish Treasure ships on the Pacific Coast of Panama before making another attempt at finding the North-West Passage and then returning home via the Asian route.

As relations continued to sour between England and Spain, King Philip of Spain ordered that all English ships in Spanish and colonial ports be seized abruptly in 1585. Elizabeth retaliated by issuing 'Letters of Marque' to English captains, including Drake, to gain 'compensation' for the English ships by attacking Spanish possessions. The obvious target for these captains was the Caribbean. In that same year, Drake sailed to the Caribbean with a huge fleet of ships and ransomed the mighty ports of Cartagena and Santa Domingo whilst disrupting Spanish shipping and the Spanish Treasure ships once more.

Continued English attacks on Spanish colonies in the Caribbean was a key factor in the King of Spain launching his ill-fated Armada against England in 1588. Its defeat confirmed the rising maritime status of England and merely emboldened its sailors to continue to challenge the Catholic power. Having said this, in the Caribbean at least, the Spanish were slowly learning from their previous mistakes and under preparedness. Their towns were becoming fortified and they deployed ever more ships and cannons to the region. The next English flotilla in 1595/6 led by John Hawkins and Francis Drake came to disaster as the former died of disease at San Juan and the latter dying similarly near Nombre De Dios. Fittingly he was buried at sea near to the scene of his greatest triumph off Porto Bello in 1596.

The other notable Tudor sailor to take an interest in the Americas was Walter Raleigh. He had actually attempted to 'plant' a colony at Roanoke in North America in 1585 but war with Spain had disrupted communications and its settlers mysteriously disappeared. Raleigh was inspired also by the tales of El Dorado which had done so much to motivate so many Spanish adventurers. Raleigh undertook two expeditions to the Caribbean to search for his city of gold in 'guiana'. On both occasions, he used Trinidad as a base of operations and to gather intelligence before exploring the Orinoco Delta and convincing himself of the tantalising proximity of its location. Raleigh's ultimate failure combined with his attacking of Spanish possessions was used as the pretext to have him executed back in England in 1618. He had already fallen out of favour with James I, but this execution demonstrated that what went on 'beyond the line' was not always forgiven and forgotten when it suited the home government. Raleigh's over optimistic writings about the 'riches' of Guiana and the 'friendliness' of the native peoples there had the effect of encouraging some of England's very first settlers to the region. 1604 saw a doomed attempt to settle at Waiapoco River between Spanish and Portuguese territory on the Caribbean coast of the Spanish main. The following year saw a relief colony heading towards the Guiana settlements be blown off course and landing on St. Lucia instead. This was England's first Caribbean island settlement as 67 settlers set about attempting to build shelter and find sustenance. However, it was not to last long as local Caribs, who had initially been friendly, turned on the settlers over a disagreement about a sword being presented as a gift. All but 19 of the settlers were wiped out and the remainder wisely fled. A similar occurence on Grenada in 1609 ended in a similar manner but with even fewer survivors to tell the tale. Although Raleigh may have failed, his tall tales and his doomed attempts still laid the foundations for Britain's interest in the Southern Caribbean and in Guiana for many years to come.

| | The Stuarts: Sailors and Settlements | |

Although the Spanish claimed the Americas as a whole as their own, they did little to interrupt or deter English sailors from exploring and indeed settling in North America. The vast distances combined with Spanish satisfaction of their economic opportunities in their two huge viceroyalties of Mexico and the Caribbean and Peru (which was actually the rest of South America) meant that they felt little compulsion to spend excessive time and effort searching for and evicting fellow continental interlopers. They did, however, continue to claim exclusive rights in all of the Americas.

Despite Spanish regional hostility, the English colony of Virginia established after 1607 was to have a profound impact on long term English (and later British) interest in the Caribbean. The way that the trade winds operated meant that in order to reach the colony it was best to cross to the Caribbean and then sail up the East Coast of North America. This meant that ships were likely to want to gather fresh food and water after making the Trans-Atlantic journey and so began to map and visit the islands of the Caribbean on a more systematic basis. The first island to come to the attention of the English, initially through ships being wrecked there, was the more northerly located Bermuda. Additionally, the colony of Virginia only survived thanks to the discovery of the economically viable tobacco plant. This plant was easy to plant and cultivate, although it quickly exhausted lands it was planted upon, creating its own imperial dynamic. It was soon appreciated that tobacco was actually a native crop of the Caribbean and so entrepreneurs surmised that the Caribbean islands might make for the best locations to grow this new crop. It was on this basis that the first serious English colonies were 'planted' on St Kitts from 1623, Barbados in 1627 and Nevis in 1628. Although the crop did indeed grow in the tropical climate of these Caribbean islands, the settlers themselves did not do so well and many succumbed to disease. Attempts at maintaining settler population with indentured servants fared little better. Furthermore, the price of tobacco took a nosedive in the 1630s as over production in Virginia and from the Caribbean islands undermined its value.

Diversification of both crops and workforce was soon regarded as an absolute necessity. Maize and cotton found limited success, but it was to be sugar that provided the economic foundation of the Caribbean economy for the next two centuries. Much of the expertise in growing sugar was brought from Dutch planters especially after many were forced to flee from Brazil in the face of the Portuguese reconquering their colony from their Protestant rival. The first successful transplantation of sugar was to Barbados and organised by James Drax. He actually started the process before the Dutch were forcibly evicted from Brazil, but when the Portuguese seized the Dutch sugar plantations there in 1645 the price of sugar increased massively. Drax and other early adopters became wealthy overnight. Other settlers were drawn to this valuable new crop and started the transition, eagerly buying up Dutch refugee expertise. Drax and the other early adopters were able to use their new found wealth to expand the land under cane cultivation and to improve their production facilities.

The Dutch not only brought their expertise but brought their slaves and trading networks with them also. This helped to deal with the second problem of maintaining a suitable workforce. African slaves were found to be much hardier and resilient to the tropical diseases found throughout the Caribbean than European settlers - indentured or otherwise. Africans could also be brought over relatively cheaply, if brutally, by the favourable Trade Winds from Africa. Soon, sugar eclipsed all other plantation crops as the insatiable demand for it in Europe outstripped supply.

Disease was a recurrent problem in the Caribbean settlements. The combination of tropical weather, poor hygiene, poor medical understanding and significant population shifts including ships arriving crammed with slaves in the most appalling conditions meant that settlers had a high chance of dying of some nasty tropical condition. It is estimated that in the Seventeenth Century, a third of all new settlers were dead within three years of their arrival in the Caribbean. Many others were afflicted but survived with scars or marks to tell the tale or lost loved ones such as children, spouses or parents. Slaves, although considered hardier compared to local Amerindians, still suffered appallingly also. It is perhaps not surprising that the churnage of settler population in the New World tended to be from the tropical Caribbean towards the North American colonies. It is estimated that some 2,000 settlers from Barbados moved to Virginia in the mid-Seventeenth Century. These settlers brought their views on slavery and plantations with them helping to unify imperial attitudes in the New World. A steady trickle to the Carolinas in the coming century also reinforced this Caribbean 'planter' view on predominantly 'Southern' American colonies. Still, those heading out from Europe to make their fortune were increasingly likely to go to the Caribbean than North America as stories of the wealth of sugar planters began to eclipse those of tobacco planters. It was also an overwhelmingly male destination with some 90% of settlers to the Caribbean being men. Few thought it an ideal place to raise a family.

The late 1630s and 1640s was a time of political turmoil back in England as Civil War raged. Thanks to the links to Dutch settlers and traders, the isolated English colonies took to supplying the profitable Dutch re-export market through Amsterdam. The English Civil War also strengthened the trading ties between the small English colonies in North America and those of the Caribbean. Whilst Barbados in particular was converting virtually all of its available land for sugar cane production, it was no longer growing enough food stuffs to provide for its, by then, sizeable population. Indeed, Barbados had become the largest English colony in the New World by the 1640s reaching a population of 30,000 by 1650 more than twice as much as the Virginia and Massachusetts colony combined. New England producers clubbed together to build their own ships in order to provide the Caribbean with food grown there. Rhode Island in particular traded heavily with Barbados. The colonies were beginning the process of becoming self-sufficient amongst themselves as the Civil War forced the isolated colonies to fend for themselves for an extended period of time. Even when Parliamentarian forces were in the ascendent, Royalist privateers attacked merchant ships and isolated communities. In reality though, whilst the Civil War raged, most English attention was paid to events in the British Isles and little thought was given to those communities across the Atlantic Ocean.

The fledgling Caribbean colonies stayed mostly neutral during the Civil War but feelings and loyalties were strained by the 1649 execution of King Charles. Bermuda declared for the new King Charles II as did Barbados and Antigua. Parliament sent out a fleet under Admiral Ayscue to bring the most important colony, Barbados, under Parliamentarian control. A tense stand off occurred with several skirmishes between the forces loyal to Parliament and those loyal to Charles II. However, as news of Royalist and Scottish defeats back in England filtered across the Atlantic, the isolated Royalist cause faltered. A generous settlement was initially offered to the Royalist ringleaders although this generosity was later curtailed by the English Parliament.

The Civil War also saw another infusion of reluctant settlers to the Caribbean as the Parliamentarians took the opportunity of despatching many of its Royalist captives to the Caribbean as indentured servants. These were joined in later years by Scottish and Irish indentured servants as Parliament's battle-hardened army swept all before them. These servants were treated far less leniently than the volunteer indentured servants of the 1620s and 1630s. Although, it did have the longer term consequence of laying down a sizeable population with royalist and Catholic sympathies which would later welcome the Restoration.

As the Parliamentarians ultimately triumphed they sought to impose their control over the isolated colonies throughout the 1650s. First by introducing Navigation Acts which banned English colonies from trading with foreign ships or markets. It was aimed principally at the Dutch and provoked the First Anglo-Dutch War. It was based on a Mercantalist conception of how trade worked which came to dominate trade policy for the next two centuries. Essentially, they believed that trade was a zero sum game and that if your competitors took your trade you were worse off. Consequently, policies were pursued that forced English products to be traded in English ships to English ports. Although this kept prices higher than they needed to be, they did at least guarantee a market for the produce of the English colonies and they also promoted the development of an English merchant marine that would ultimately challenge the Dutch and other European powers for pre-eminence throughout the region and further afield.

Oliver Cromwell's other major policy to assert control in the Caribbean was his 1653 so-called 'Western Design' concept. Cromwell ended his trade war with the Dutch and turned his attention back on to Catholic rivals. This 'Western Design' was a significant milestone in the history of the Empire. Hitherto, all colonies and settlements had been set up as private ventures by interested parties who generally were in the pursuit of profit or religious freedom. Up to this point any attacks on enemy settlements had generally been raids in the pursuit of plunder and supplies. Oliver Cromwell's decision to send a fleet to the Caribbean to attack and capture Spanish colonies and turn them into English colonies was a step change in policy. Now, the government of England was directing the expansion of her empire directly for the first time in its history. Spain was the obvious target for Protestant England and her isolated Caribbean colonies appeared to offer low hanging fruit for the well oiled English Army to plunder and capture. A large fleet set off for the Caribbean where it was swelled in Barbados by additional English recruits from across England's Caribbean colonies. Their target was the main Spanish settlement in the Caribbean on Hispaniola but unexpected Spanish resistance, tropical diseases and poor morale from the recently raised local rabble saw the attack end in ignominious failure. The Commanders Admiral William Penn and Commander Robert Venables attempted to save face by moving to seize the far more lightly defended Jamaica in 1655. Initially successful landings were soon undermined by a determined guerilla war as the Spanish released their slaves into the interior and led harassing attacks on the diseased and increasingly hungry English invaders. Two attempts to recapture the island by the Spanish in 1657 and again in 1658 were only foiled by the inspired leadership of the military governor Edward D'Oyley. Penn and Venables both returned to England in disgrace with a fraction of the forces they had set out with. Jamaica was regarded as something of a disappointment as its large size, mountainous terrain and hostile ex-slaves (Maroons) at large made it more difficult to cultivate sugar on and to administer. The smaller islands of Antigua, Barbados, St. Kitts and Nevis were all much more manageable and hence profitable.

The Restoration of the monarchy back in England in 1660 did not see a significant change in colonial policy. The Navigation Acts were reissued and many of the key governors such as Edward D'Oyley were kept in place in order to maintain a sense of continuity. The King in England did not wish to overly antagonise his subjects unnecessarily.

All these initial colonies had been granted self-governing assemblies along the lines of those in North America. They therefore had considerable powers and freedom but these were generally concentrated into the hands of propertied, monied and well connected settlers who often used their powers to their own benefit. Increasingly harsh codes were enacted to keep slaves in their place and to punish any transgressions severely. The isolation of these colonies from support from England meant that they felt vulnerable from attack from the French, Dutch or Spanish in the various wars that raged in the second half of the Seventeenth Century. Jamaica came up with a novel way of defending itself by actively encouraging 'buccaneers' to settle in Port Royal and use it as a base for their operations (as long as it was against their Catholic rivals). The 'buccaneers' had had their own interesting evolution. In general they were a mixture of English and French Huguenots who had been turfed out of St. Kitts in 1629 or Providence Island in 1641 by the Spanish in one of their many attempts to reestablish their control in the Caribbean. The buccaneers had settled in Tortuga or along the north coast of Hispaniola hiding from the Spanish in particular. They had attempted to make a living by hunting and skinning wild cattle and selling the hides (boucan - which is where their name derives) to passing ships. But over time they found anti-Spanish piracy to be much more to their liking and far more profitable. Therefore, the invitation to come to Jamaica and work alongside the small English fleet in the Western Caribbean with a measure of defence in the newly fortified Port Royal was an opportunity they could not miss. It would not take long for Jamaica to earn its reputation for piracy and violence and as a result it was indeed largely spared attack from England's rival European powers.

War between England and Spain officially ended in 1670 with Spain finally agreeing to recognise England's claim to Jamaica. Unfortunately, England's ability to restrain the pirates and privateers operating on the opposite side of the Atlantic was less than its desire to do so. One of Jamaica's more notorious freebooters was Henry Morgan who took a force to sack the Spanish settlement of Porto Belo in 1668 and then another even more impressive expedition across the isthmus to sack Panama in 1671. The problem with this latter adventure is that it was conducted well after the 1670 Treaty ended the war with Spain. Both Morgan and the governor of the island,

Sir Thomas Modyford, were recalled to London to explain themselves. The brazen Henry Morgan was able to sweet talk his way past the King who sent him back to Jamaica as Governor although with the understanding that he would bring piracy under control. A significant nail in the pirate's coffin was in 1685 when the first English naval squadron arrived in Port Royal for permanent patrol and defence in the region. Another nail came in the form of what many contemporaries regarded as divine intervention when an earthquake and tidal wave in 1692 devastated Port Royal. Further earthquakes and hurricanes plagued the infamous port time and again over the subsequent years meaning that Port Royal soon became nothing more than a suburb of the relocated capital at Kingston. The problem of piracy was reduced in Jamaica, but certainly not from the region as a whole as pirates and buccaneers sought alternative ports and bases for their operations. A significant number of pirates relocated to the Bahamas but these were also attacked and harried by naval vessels who eventually captured their main base at New Providence Island in 1718. By the 1730s piracy had been reduced to negligible instances by the increasingly professional and powerful Royal Navy.

External enemies were not the only threat to European planters on these isolated islands. As the number of slaves inexorably increased so did the threat of revolt and rebellion. Slave owners felt that one way to guard against slave rebellion was to ensure that their slaves came from a variety of tribes from Africa and spoke differing languages to one another. However, over time these slaves did manage to evolve a common creole which also incorporated the language of the overseers who made heavy demands in requiring a quick understanding of their commands and orders. Increasingly, attempts to divide and rule became ineffective as slaves living cheek by jowl learned to communicate and work together. Barbados, as the first island to transform itself into a plantation economy suffered the earliest attempted and real revolts from the 1670s onwards. The so-called Coromantee Plot of 1675 was planned meticulously for many years before being betrayed by a domestic slave who felt pity for the impending doom for her master and mistress. She was rewarded with her freedom whilst the conspirators were treated with unspeakable harshness: six slaves were burned alive, eleven were beheaded and 25 others were executed. The carrot and stick approach was to remain a powerful tool in the armoury of the authorities for as long as slavery was a legal institution in the Caribbean.

Back in England, 1688 saw a significant political shift that would cause long term ripples in the Caribbean. The Glorious Revolution saw the Dutch King William of Orange with his Stuart wife come to the English throne in place of the Stuart James II. The consequence of this shift in the Caribbean was that Holland would no longer be the main colonial rival for England as she had been for much of the Seventeenth Century. Increasingly France would fulfil the role as principal rival as the relative power of Spain and Portugal continued to be eclipsed. France, on the other hand, was fast becoming the most important Continental power and she had considerable imperial ambitions of her own. Almost Immediately with the accession of King William of Orange, war with France was declared which raged until 1697. During this war, the isolated Caribbean colonies of all European nations became pawns which were attacked, sacked and captured with alarming regularity. All the effort expended was often undermined by generous peace treaties which tended to return these colonies to their ante-bellum status.

It should be said that despite all the nationalistic posturing, often the planters did not always want to capture rival European islands as they did not want to expand the amount of sugar available to sell and hence watch their profit margins decline. They were happy to raid and pillage other colonies but the established plantocracy was generally content with the privileged and monopolistic access to British and colonial markets. The Navigation Acts appeared to be a burden, but corruption and bribery could often be used to circumvent the more onerous aspects of these laws. The constant fighting tended to see yet more concentration of power into the hands of the planter elite as they sent out the poorer whites to do the fighting (and dying) whilst they bought up vacant lands from the deaths of smallholders. If the British islands had likewise been ransacked, it was generally the well to do planters who had the economic ability to rebuild their plantations. Smallholders ended up joining military reprisals or selling up altogether, usually to the planters, and heading to North America to start all over. The proportion of whites to blacks continued to fall and the constant state of warfare only exacerbated that trend.

One institution established by William of Orange was the Lords of Trade and Plantations in 1695. In many ways, it was the fore runner of the later colonial office. It was an attempt by the English government to provide oversight of the local colonial legislatures that were in place and had the right to over rule their laws if they conflicted with imperial trade policies - ie the Navigation Acts. The board would also nominate Crown governors and recommended laws affecting the colonies to the British Parliament. In effect, it was formalising England's Empire and the fact that it had the appendix 'and Plantations' clearly demonstrated that the Caribbean colonies were the central concern of this new institution. It was creating institutions to attempt to harmonise imperial policy which was not always easy when the priorities of, invariably the influential, settlers often contrasted and conflicted with those of the home government. Although the home government held strong cards in the form of providing defence for these isolated and dispersed colonies and also providing privileged access to markets for their products. Often colonial legislatures would vent and discuss imperial policies at length before bowing to the inevitable and having to accept the Lords of Trade and Plantations' recommendations.

One Caribbean scheme that had unexpected ramifications back in the British Isles was the attempt by the Scottish to create a trading company at Darien on the Isthmus of Panama in 1698. This was something of a mercantile response by Scottish traders and politicians who were concerned that they would be frozen out of international trade unless they had their own colonies to trade with. Panama had been identified on strategic grounds as being perfectly located between the increasingly economically important Caribbean and the Pacific and between North and South America. There were further dreams of cutting a canal between the two tantalisingly close bodies of water. Unfortunately, it was not appreciated that the Darien peninsular was little more than a malarial swampland surrounded by hostile Spanish concerns who would have attacked the Scottish settlement had it demonstrated any semblance of success. As it was, this was unnecessary as it became obvious that the under-capitalised and naive Scottish trading company was barely surviving let alone thriving. In 1700, the isolated and bedraggled colony forlornly surrendered to the Spanish. The failure of this scheme caused a major scandal back in Scotland and was one of the prime reasons that Scotland sought a Union with England in 1707. Indeed the Act of Union specifically agreed to repay the Darien creditors any money lost on their imperial scheme. Additionally, Scotland after the Act of Union was no longer barred by the Navigation Acts from trading with English colonies and ports. Scottish traders and merchants would soon become a very influential group of colonialists and many of them travelled to the Caribbean to establish trading houses and develop commercial ties with what were now British Caribbean colonies. Glasgow itself became a hub in the tobacco trade whose 'Tobacco Lords' rose to be some of the richest people found anywhere in the British Empire.

With barely five years breathing space, the European powers were once again at war from 1702 to 1713 with the War of Spanish Succession which once again pitted the English with the Dutch against the French and the Spanish. Once again the isolated Caribbean colonies provided easy pickings for fleets of both nations. It also disrupted trade and brought severe hardship and famine to various parts of the Caribbean. In this particular war the English (or British as they had become after 1707) came out slightly ahead of the French when they were able to evict the French colonies from the long disputed St. Kitts island. They were also able to gain the Assiento from the Spanish which finally, after a century and a half after John Hawkins' attempts to do so, allowed the English to supply slaves to the Spanish Main. The optimism created by this event would end up causing one of the great financial bubbles of all time back in Britain. The company given the right to trade slaves with Spain was the British 'South Sea Company.' In fact, this company was granted a monopoly for all trade between the British Empire and the Spanish Empire as mercantile conceptions of international trade continued to hold sway over decision makers. Various traders, merchants and sailors had dreamed of trading with South America for so long and had waxed so lyrically about the opportunities there, along the lines of Walter Raleigh from a century before, that it led to investors greatly over estimating the economic value of trading with South America. The Spanish Empire was no longer the great power that it had once been. It had been exhausted by years of war and its own merchants and businesses had ossified under stultifying Royal Court control and lack of investment. It was a shadow of its former glory but this did not stop British investors imagining the South America of 'El Dorado' or the 'Potosi Silver Mines'. The value of the South Sea Company appeared to defy gravity and more and more investors rushed in to buy more shares sending the value of the company ever higher still. The bubble did not burst until 1720 but when it did, the value of its shares fell spectacularly. The vast majority of investors lost their paper fortunes and their original investments also. Interestingly, the French economy was undergoing its own bubble and collapse connected to the New World. John Law, a Scottish adviser to the French Crown, had set up a Mississippi Company with similarly optimistic ideas of trading with the New World through their control of the Mississippi River system despite the fact that the largely nomadic peoples of North America barely having any money or resources to trade. The collapse of both companies in 1720 provided a reality check on the unbridled economic optimism for the New World. There would be economic opportunities, but these would have to rely on the time honoured practice of hard work, investment and the selling of real produce.

| | The Hanoverians: Sugar and Slaves | |

Scotland's Union with England in 1707 was followed in 1714 by a change in Royal dynasty as the Hanoverians replaced the Stuarts. Britain's mercantile restrictions on trade and the awarding of Royal monopolies had an unexpected effect on the flow of trade in the Eighteenth Century. London merchants, thanks to the Navigation Acts, had been granted the monopoly to import (and then re-export) all goods arriving from the Caribbean. This was deeply resented in rival ports like Liverpool and Bristol. There were two consequences over the coming century. Firstly, London grew to be an enormously wealthy trading entrepot through the sugar trade in particular. Secondly, Bristol and Liverpool found a way around the monopoly through sending their ships with locally produced goods to West Africa where these were exchanged for slaves. These slaves were then taken, in terrible conditions, to the Caribbean islands, usually to Barbados which was the easiest British controlled island to reach from Africa using the Trade winds. These slaves were then sold and the money raised used to purchase sugar and sugar based goods for the return journey across the Atlantic to London. Once they had stopped in London and paid the necessary taxes and dues they could then take the trip back to their home ports, often carrying the now legally imported sugar or perhaps exchanging their cargoes for other internally traded goods to start the process again. This is often referred to as the Triangular Trade, but there was this important and bureaucratically necessary fourth leg required to comply with the restrictive Navigation Acts.

The 1710s and 1720s saw the twilight years of piracy rear its ugly head once again. This sudden increase was partly in reaction to the end of the War of Spanish Succession where privateering and piracy could be couched in nationalistic strategic terms. Furthermore, on the outbreak of peace many mariners found that their skills were no longer in such strong demand from the warring nations and so freelance piracy offered a career path to some. Peace also saw a resumption of normal trade patterns and the triangular trade offered increasinlgy rich pickings. Caribbean based pirates ranged far and wide from the coast of West Africa up to the rocky coasts of Newfoundland and virtually every inlet in between. The Royal Navy fought a determined campaign to reduce the scourge of piracy although in doing so, they often found themselves in the unpalatable position of guarding the wretched slave ships from pirates who might offer better terms for the unfortunate passengers than those that awaited them on the quaysides of the Caribbean.

Yet another danger of living and working in the Caribbean were the powerful and unpredictable hurricanes. Individual islands could go for many years without being affected in any significant way and then out of the blue a devastating hurricane could destroy buildings, rip up plantations and cause chaos in the local economy. Jamaica, for instance, was hit be huge hurricanes in 1722, 1726 and 1734. Antigua was hit by a devastating one in 1728. Perhaps the only saving grace was that it was not just the British islands that were afflicted, rival French settlements also had to endure them with Guadeloupe being hit in 1713, 1714 and 1738. When the weather was combined with disease and the occasional earthquake it is not hard to see why life in the Caribbean was precarious and impermanent.

Despite all these travails, sugar continued to dominate the Caribbean economies during the Eighteenth Century and its appeal and popularity in the newly industrialising Britain meant that London became the centre of world trade for the commodity rather than any Dutch, French or Spanish centres. Sugar provided energy for those working in the newly expanding factories and also complemented the latest fashionable drinks of coffee and tea which were also experiencing a complimentary rise in popularity. The price of sugar went from 24 shillings a cwt in 1727 to 42s a cwt by 1757 despite an enormous rise in production during this period. The sugar plantations required large amounts of capital and a considerable supply of labour and it would often take many years before plantations started making a return on any investment. This meant that it was not to be British small holders or poor emigres who would benefit from the crop. Rather, it was generally the already established, resourced and well connected, often already existing aristocracy, who benefitted. The primogeniture system in England meant that the eldest son tended to inherit all the English estates and titles. Second and subsequent sons might be packed off into the clergy or armed forces, but many of these younger sons were given some capital by a parent to go off to the Caribbean and use their family name and connections to establish themselves as a planter often taking their social prejudices and privileges with them. The idea of a social hierarchy back in Britain made it all the easier to accept the institution of slavery in the colonies with its starkly defined roles and obligations set out clearly for all to see. And the fact that plantation houses were isolated in seas of a reluctant and hostile work force meant that laws to keep slaves in their place and prevent them from either running away or rising up against their masters were incredibly harsh. Indeed, they got progressively harsher as the century wore on and reached a peak of brutality in light of French slave uprisings on Saint Domingue at the end of the century.

The Eighteenth Century saw some, but by no means all, of the sugar plantocracy make fortunes. These came to be known as the 'Sugar Kings'. Some of these planters, or their children, crossed back across the Atlantic to England to buy their own estates in England often with accompanying seats in Westminster. These Sugar Kings became an increasingly important lobby group in Parliament as they sought to defend their trading privileges and access to slaves. They were joined by MPs from the ports of London, Bristol and Liverpool in preserving the Navigation Acts and Slave Trade even as criticism against slavery began to swell during the latter half of the Eighteenth Century.

Those Sugar Kings who did return to Britain to take up parliamentary careers or manage more traditional English estates left overseers and managers in place back in the Caribbean. Disease and the ever present brutality of a slave economy meant that many families were keen to leave the Caribbean as soon as they possibly could - even if the estates there were the source of their wealth. The next generation of overseers and managers were often even more removed from the welfare of the workforce of these plantations as they were motivated by results for their own income. The treatment of slaves became even more brutal and their hours worked invariably increased in order to satisfy production targets. The absentee landlord became an accepted part of the island economies.

Despite the use of slave labour, technology still had its role to play in the island economies. The most important part of sugar production which benefitted from technology was in the sugar mill. Slaves would cut the sugar cane and bring it to the mill where huge rollers would crush the all important juice from the tough fibrous plant. Speed was of the essence before the cut cane spoiled. Initially, planters used animal power, cattle or horses, to power the rollers but soon, inspired by Dutch settlers, windmills were used. The first one used in Barbados was constructed by a Dutch adviser working for James Drax in 1644. These were ideal on the isolated small islands as long as the wind was not too strong nor too weak - animals were still kept in reserve. By 1674, there were more than 260 windmills on that one island alone.

Britain's own industrial revolution would eventually spill into the New World also. The advantages of steam providing a continuous flow of uninterrupted power was being harnessed back home and many of the Sugar Kings had the money to invest in this new technology. The first steam engines to power sugar mills appeared on Jamaica from 1768. The early models were still unreliable and prone to mechanical failure or even explosions. Also, the technical knowledge to run and operate these machines had to be shipped over from Britain with the engines themselves. Plantation owners were also concerned that industrialisation might lead to another argument against the use of slave labour, although the fact that steam engines could not cut sugar cane should have made this a moot point. Consequently, the spread of steam power was slower than the spread of wind power had been. Still, from 1810, the reliability and operating costs of steam power meant that they became an increasingly important aspect of the local economies.

In 1733 the British government attempted to use economic policy to encourage imperial products and markets through the introduction of the Molasses Act. Up until this point, the Navigation Acts had merely restricted the use of foreign shipping for trade between England and its colonies (and vice versa). There had been nothing to stop, however, a British or colonial ship from stopping in a foreign port and loading French or Spanish goods and taking it to a another port. The Molasses Act was designed to impose a tax of six pence per gallon on imports of molasses from non-English colonies. It was principally designed to discourage the 13 American colonies from buying French colonial sugar products instead of British ones. Molasses were particularly useful in the production of rum which was increasingly popular throughout the Americas. It also started tp be used as a barter trade for slaves as the American colonies began their own version of the Triangular Trade. French molasses were consistently cheaper due to the fact that French protectionist measures were in place to guard the politically well connected domestic Brandy industry. This law also demonstrated the rising political power of the 'Sugar Kings' who helped steer it through Westminster for their own benefit. It was never designed to raise revenue, but merely to discourage the purchase of foreign sugar products. The law was greatly disliked in the American colonies and smugglers frequently circumvented the paying of the required customs making a mockery of the law. In 1764 it was replaced by the sugar tax which halved the tax required but provided for stricter enforcement. The reduction of the tax did little to appease settlers in the American colonies who regarded it as an example of British mercantile policy undermining their own economic opportunities and artificially raising the prices of goods they wished to consume. It also revealed that Britain regarded the economic well being of the Caribbean colonies was more important than that of the American colonies. The small sugar islands were producing disproportionately more wealth for their size than any of the North American colonies. Furthermore a lot of that wealth returned to Britain with the Sugar Kings who used it to further their own political power, whilst money made in the American colonies tended to stay in those colonies. Ultimately, these two acts became regarded as grievances leading towards the American Declaration of Indepdendence in 1776.

The War of Jenkin's Ear from 1739 was provoked by Caribbean transgressions between British and Spanish traders regarding the Asiento. Originally, the agreement had defined the quantity and goods that Britain could trade with Spanish colonies, but it soon became apparent that once the principle of trade had been opened, smugglers filled any surplus demand. Captain Robert Jenkin's vessel was boarded by Spanish officials off the coast of Havana and his ear cut off as punishment for illegal trading. This provoked cries for war back in Britain which soon could not be resisted. This war was different from previous conflicts which had had their genesis in dynastic struggles back in Europe. The War of Jenkin's Ear started in the colonies and principally revolved around imperial trade. Once again, the war started well for the British who once again captured Porto Bello in Panama. But a 1741 expedition to Cartagena and Santiago de Cuba ended in disaster as 22,000 of the 28,000 despatched died, mostly from disease. Worse was to occur as the French joined the Spanish and privateers once again could sail not only with impunity but with active encouragement from respective nations. By the conclusion of the war, little had been gained other than the American colonies strengthening their maritime trade links with the Caribbean at the cost of the long voyages from Europe.

It was during this war that the Royal Navy made its switch from issuing Brandy to its sailors to Rum. It was formalised by Admiral Vernon who also went by the nickname of 'Old Grog'. His written instructions to his captains stipulated that rum be diluted with water and was issued to sailors twice a day. This rationing helped reduce drunkeness whilst still making alcohol available to the sailors in a controlled setting. But the switch from French Brandy to colonial rum helps illustrate the growing importance of the sugar islands to British institutions and ultimately to military identity. To drink rum was to become synonomous with being patriotic whilst drinking brandy was to support the tyrannical French.

The story of the European Empires in the Eighteenth Century Caribbean was increasingly linked to the success of sugar as a plantation crop and one way to hurt your enemies was to destroy their economic base by raiding or later capturing the all important and all too isolated plantation islands. This was demonstrated most dramatically during the Seven Years War when the British captured nearly every significant French or Spanish sugar producing island including: Dominica, Tobago, St Vincent, , Guadeloupe, Grenada and the Windward Islands. The only one they did not take was the French island of Saint Domingue. As if to illustrate the perceived value of the sugar islands, at the conclusion of the war the French were given the choice of ceding Canada or Guadeloupe to Britain. Without hesitation the French chose the profitable Caribbean island over the icy wastes of Northern America. Similarly, Spain chose to swap its claims on Florida for the far more profitable Cuba which the British had also managed to capture. Sugar islands were still regarded as economically vital to the Mercantalist Empires of Europe.

The primary reason for Britain's success in this war was its increasing investment in the Royal Navy which allowed the small country to project power across the globe and to assert itself to its economic advantage in places like the Caribbean. The investment in the Royal Navy had to be paid for however which is one of the reasons that taxes such as the Sugar Tax were implemented so soon after the war. Attempts to raise revenue would soon see the 13 colonies agitate for independence and would cause severe disruption throughout Britain's Caribbean Empire.

The Eighteenth Century also saw a massive increase in the brutal efficiency of slavery as more manpower was needed for the increased amount of sugar consumption. Britain's increasing maritime skills and capacity were employed all too efficiently to pick up slaves from West Africa and bring them to the Caribbean as chattel. The white population of the sugar islands were becoming increasingly outnumbered by the black slave population required do undertake the back breaking work. In Antigua for instance the slave population outnubered the Europeans by 10 to 1. Plantation houses increasingly took on the demeanour of forts and castles as isolated Europeans feared slave revolts or rebellions.

Slave codes became progressively harsher in light of slave uprisings or gangs of escaped slaves living by theft and their wits. Barbados' 1661 'Act for the Better Ordering and Governing of Negroes' became a template copied throughout the Caribbean colonies and into the plantation economies of North America. This particular act put racial identities above economic ones in an attempt to secure the loyalty of poorer white settlers to the ruling planter classes. For example, a slave who assaulted a white person, of whatever status, was to be whipped. If the offence was repeated he was to be whipped again and to have his nose slit and his forehead branded. White people's right to a Trial by Jury harked back to ideals of Magna Carta whilst denying the same rights to black slaves who had to contend with locally convened kangaroo courts organised by their masters. Slaves in British colonies were to be treated far harsher than slaves in Spanish or French colonies whose codes included the encouragement of Christian baptisms and advocates for slave rights. There was no such protection in British colonies except in Trinidad which the British were later to take from the Spanish and left the Spanish codes largely in place. However, in most British colonies the severity of punishments only escalated. Even the most minor offences could result in whipping, beating, chaining to the ground, having ears or cheeks bored through with a hot iron or being hung and left prominently on display to deter other slaves from considering dissent or escape. This did not stop slaves from escaping or organising rebellions and revolts. Escapees tended to be more successful on the larger islands like Jamaica where it was harder for the authorities to scour the countryside and consequently easier to disappear. Indeed the size of Jamaica had made it possible for the descendents of Spanish slaves to live in their own communities in the central highlands. The 1730s saw a protracted war waged by the British to attempt to bring two separate groups of Maroons under control. In the end, they had to seek an accommodation with one of the Maroon groups on condition that they not help escapee slaves and help the authorities with any rebellions. This deal was honoured by the Maroons in the 1760s when a significant and coordinated slave uprising called Tacky's Rebellion broke out. Over 60 Europeans were killed as the rebellion spread through large tracts of Jamaica. It took over a year for the British to reassert full control and they had had to rely, if somewhat ironically, on the support of Maroons to re-establish order. This particular rebellion encouraged a new set of even harsher slave codes as the spiral of repression and despair continued its downward direction.

The only significant opposition to slavery, or at least the worst excesses of slavery, came from religious thinkers. Criticisms against the harshness and degradation of the institution of slavery came mainly from non-Conformist churches such as the Quakers although even these initially could not conceive of the idea that slavery be abolished. Rather, they tended to call for a more humane application of laws and treatment to the slaves. This is not to say that the official Church of England did not become involved in the debate. In the Seventeenth Century, nearly all visitors and commentators on the Caribbean island colonies commented on how godless and selfish these societies appeared to be. As a consequence the Church of England was asked to create the "Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in Foreign Parts" by King William specifically to improve the quantity and quality of ministers heading over to the Americas. Like th early non-Conformists, these ministers were not to challenged the status quo and accepted the right of the institution of slavery to exist but they also began the process of regarding the African slaves as being God's children also. As the preacher for the 1711 Society Annual Sermon put it: 'Negroes were equally the Workmanship of God with themselves (the planters); endowed with the same faculties and intellectual powers; Bodies of the same Flesh and Blood, and Souths certainaly immortal'. No less a person than the conqueror of St. Kitt's and defender of the British Empire of the Caribbean during the War of Spanish Succession, Christopher Codrington (the younger), left a substantial bequest in his will to create a college to be donated to the Society for the care for the spiritual and physical needs of the slaves in the Caribbean. Proving the complexity of the issue, part of the bequest given to the Society included large tracts of Barbuda and two very profitable Barbados plantations. This meant that the Church of England was actually receiving slaves as part of the plantations to pay for a college to benefit the treatment of slaves. This helps illustrate that at this stage, it was the treatment of the slaves that caused some unease rather than the ownership of slaves per se. Over the Eighteenth Century, however, attitudes would harden especially with the conversion of more and more slaves to Christianity. It would become increasingly difficult for the various Churches to turn a blind eye to the suffering of their parishioners. Non-Conformists would take the lead in the coming century, but even the Church of England would find it increasingly embarrassing to be slave holders themselves.

Quakers became more and more hostile to the thought of owning slaves and in the 1750s and 1760s they began to actively campaign against slavery as an institution and demanded that all slaves should be given religious instruction and freed. They began to pressurise other Quakers to relinquish their slaves and those who refused to do so were shunned from meetings of 'Friends'. Quakers were a small sect though and were regarded by many mainstream Christians as already having strange views on a whole number of issues and so were often politely ignored. The big breakthrough in mainstream Christianity came in 1774 when John Wesley visited South Carolina and witnessed slavery first hand which he recounted in Thoughts upon Slavery. The Methodist movement was sweeping through Britain and the Americas at this time and so his thoughts found a large and an increasingly influential audience. Criticism of slavery was moving in from the margins towards the mainstream and appeals to Christian susceptibilities was to be a key ingredient in undermining the institution in the coming decades.

| | Revolutions and the Napoleonic Wars | |

1776 was to be important for two reasons, the first is the American Declaration of Independence which would rupture Britain's Atlantic Empire but it was also the year that saw the publication of Adam Smith's Wealth of Nations which would equally revolutionise the economic rationale for the British Empire. These two events coincided with a significant long term depression in sugar prices for the first time. This was partly as a result of British success in the Seven Years War. Britain had conquered many new sugar islands from the Spanish and French and as they expanded production, with the Navigation Acts still very much in operation, so prices fell. Added to this was the fact that these new plantations required manpower themselves and so the price of slaves increased adding ever higher production costs. Many of the existing plantations survived on credit and had taken out loans to finance expansion, buy slaves, import technology or in anticipation of future cane harvests. A sign that things were amiss was when the first large bankruptcy of a planter occurred in 1774 in Barbados. The Gedney Clarke bankruptcy sent shock waves through the Caribbean and back to the lending houses of London.

Adam Smith specifically criticised the sugar monopoly and the institution of slavery in his book. He pointed out that the Navigation Acts merely made the price of sugar significantly higher for the consumer to the benefit of the producer (in artificially high prices) and the government (in the form of duties). As for slavery, he believed that with no motivation for wages the rational choice of a slave was to eat as much as possible and to do as little work as he could get away with. His book would add economic weight to the growing and hitherto largely religiously based abolitionist movement. His Free Trade ideas would take many years to replace the economic orthodoxy of mercantalism, but slowly and surely it would win adherents and expand its influence. In the short term, abolitionists encouraged boycotts of slave produced sugar in a fore runner of ethical sourcing. Non-slave produced sugar products began to proudly display their wage based labour origin.

The abolitionist movement began to be more and more sophisticated in their campaigning techniques. Brutal images were innovatively portrayed to shame consumers into considering the welfare of those who made their luxury products. Unwitting ladies might be invited to sophisticated tea parties only to find that upon finishing their delicate teas they would find an image of a slave being whipped at the base of their tea cup. Others were invited on pleasant boat trips only to find that they were being taken to see (and smell) the slave ships in docks like Bristol and Liverpool. It would take many years to reach a critical mass, but sustained and innovative campaigning ensured that the institution of slavery was being brought to the fore of political discourse and became an increasingly important, if still divisive, force in British domestic politics.

The coming difficulties between the British Government and the American colonies would place the Caribbean islands into a dilemma. They had increasingly come to rely on the American colonies for imports and foodstuffs and had also cultivated them as markets also. The islands also had many of the same concerns as the colonists regarding issues such as duties, taxation and especially the 1765 Stamp Act which required a duty on most official documentation. However they also realised that their own priorities were also diverging somewhat from the 13 Colonies to the North. Economically, the Caribbean islands were content with the existing Mercantile arrangements such as the Navigation Acts which granted their products a privileged monopoly access to British markets. Whereas the American colonies were advocating for more Free Trade and when this was not legally available many of their merchants and mariners turned to smuggling with Spanish, Dutch and particularly French colonies to circumvent paying customs and duties. In effect, they were putting Free Trade principles into place in trading with the Caribbean as a whole regardless of the legalities involved. Another key difference between the two groups of colonies was that the Caribbean islands were still deeply concerned at their security. The American colonies had had the French threat from Canada removed whereas the French colony of Saint Domingue was still a large and very profitable concern and it was assumed that the French would attempt to recover their losses from the Seven Year War in the near future. Also, the Caribbean colonies were ever more conscious at their potential need for British military support should slave revolts and rebellions occur. Indeed the 1760s had seen Tacky's rebellion in Jamaica and 1776 would see another large revolt in Jamaica - partially inspired by revolutionary rhetoric (and guns) from the American colonies. The Island colonies were under no illusion that they would require external military support to subdue any sustained rebellion and the Royal Navy and the British Army seemed to offer the most reassuring capabilities for their security. Given this increasing divergence, when the First Continental Congress decided to impose a trading embargo on the Caribbean colonies it was obvious that these isolated island outposts would remain loyal to Britain despite the ever closer regional links forged over the previous century.

The American Revolutionary Wars would cause severe problems for the Caribbean colonies throughout the 1770s and 1780s. Apart from the disruption in trade and the inflationary effect of having to import foodstuffs from Europe rather than North America, the British government raised the import duty on sugar as a revenue raising measure in order to fund their war against independence in the Americas. Furthermore, American privateers now saw the Caribbean as an open target and attacked and seized merchant shipping with barely restrained relish. They took over 250 ships by 1777 and even landed and attacked bases at Nassau and Tobago. The depression in the planters' incomes, combined with rising prices and irregularity of food supplies arriving meant that slave rebellion from hungry workers was becoming a real concern. Tobago, St. Vincent and Jamaica all underwent convulsions and revolts which only confirmed the difficulties facing the authorities in maintaining law and order as the Caribbean became an active war zone. The situation only deteriorated when France and Spain joined the American cause for independence. The loss of Dominica, St Vincent and Grenada to a large French fleet arriving in the Caribbean demonstrated that the Royal Navy was no longer in control of the seas around its strategically most important collection of colonies. The British capture of St. Lucia restored a little prestige before a fresh French squadron arrived in the region. The English declared war on the Dutch due to the fact that her Caribbean colonies were being used by American privateers to refit and sell on prizes captured from the British. The British seized the tiny but strategically important St. Eustatius and cut off an important flow of arms to the Americans as a result. Once again though a French fleet restored French naval supremacy in the Caribbean and captured Tobago before heading north to blockade the British force at Yorktown and prevent the Royal Navy from relieving the beleagured British army there. With this defeat, British authority in America had suffered an irreversible setback. The victorious French fleet headed back down to the Caribbean and set about attempting to take advantage of their naval power. They besieged St. Kitts which fell after an epic struggle and valiant defence. But once it had fallen, the Nevis and Montserrat dominoes fell with barely a shot being fired. The French then planned to attack the most important remaining British colony in the region, Jamaica. Fortunately for the British, the protracted defence of St. Kitts had bought the British time to prepare a fleet to be despatched to the Caribbean to try and salvage their empire there. This fleet, under the command of Rodney, intercepted the French fleet as it attempted to rendezvous with a Spanish fleet at Santo Domingo en route to Jamaica. The two evenly matched fleets fought what was to be known as 'The Battle of the Saintes'. After a bloody clash, the British captured five ships - including the French flagship - and sunk another and caused serious damage to many others. It had been a savage encounter and a close run battle but the effect on the strategic position of what had seemed a defeated and despondent Britain was transformative. Jamaica celebrated its salvation, the French court martialled many of its officers and the British were able to gain far better terms at the Treaty of Paris than they had dared hope for just a few weeks earlier.

It should be realised that one of the reasons that the British were defeated in the American Revolutionary War was because of the importance and priorities she had placed on defending and maintaining her Caribbean empire. Time and again, grand strategic thinking had been dictated by a desire to hold on to the all important sugar islands. For instance, one of the reasons the British had given up on its attempt to capture Philadelphia was to withdraw the soldiers to capture St Lucia. The Royal Navy had been stretched to breaking point and could not supply their armies in America and defend the Caribbean but ships were always made available for the latter even when they were outnumbered and challenged by the French and Spanish navies. The defence of Jamaica was given a far higher priority than the defence of any of the 13 colonies. Having said all that, the loss of the 13 colonies to the British Empire would have severe consequences for the British Caribbean Empire. The Navigation Acts now prohibited selling their produce directly to the newly independent United States and in 1786 an embargo on all US ships visiting British colonial Caribbean ports was implemented. The 1780s saw a succession of Royal Naval ships sent to patrol the trading highways of the Caribbean. Many of the captains turned a blind eye to illegal trading with US ships with the notable exception of one young Horatio Nelson who commanded a 28 gun frigate with vigour and a growing reputation. He was himself to marry into the Caribbean plantocracy when he wed a planter's daughter, Frances Nesbit, in Nevis.

Another interesting byproduct of the American Revolution was the infamous Mutiny on the Bounty which saw William Bligh cast adrift in the Pacific Ocean. The reason he had been sent to Tahiti was to attempt to bring back breadfruit from there to try and grow in the Caribbean to provide a cheap form of sustenance for the slave workforce. His ship was unsuited for the task of carrying live trees and plants and the cramped conditions was one of the primary reasons for the mutiny breaking out. Bligh later commanded a second expedition on a custom made ship which was successful in bringing the breadfruit to the Caribbean islands. Unfortunately, at least in the short term, the slaves did not appear to think much of this new foodstuff. Over time though, breadfruit would become a staple of the Caribbean diet.

This interest in growing foods from one part of the Empire in another would be formalised and coordinated primarily by Kew Gardens in London in conjunction with local governors during the last years of the Eighteenth and into the Nineteenth Centuries. Botanical gardens were an attempt to diversify the agricultural produce and export potential of the various colonies around the World, they also experimented with growing herbs for medicinal purposes and to provide fresh produce to local markets. Plants, trees and crops from one part of the Empire were taken to other climates to see if they fared better or worse in varying climate and altitude zones.

The first formal botanical garden in the British Caribbean, and perhaps the oldest tropical botanical garden in the World, was in St Vincent under the auspices of the governor and a military surgeon. It was established in 1765 only shortly after the island was formally granted to Britain by the 1763 Treaty of Paris ending the Seven Year War. In an unusually enlightened frame of mind, the organisers decided to interrogate local Caribs, slaves and French planters to seek their advice on local plants, potions and herbs that they may have found to have been efficacious. Additionally, they had seeds sent by the East India Company from India and Borneo. Kew Gardens sent seeds from China. Specimens and plants were also brought from other Caribbean islands to see how well they fared in St. Vincent. Jamaica followed in 1779 with its Bath Botanical Gardens. These were later joined by other gardens at different altitudes and climate zones on different islands.

The years between the American and French Revolutions were not happy ones for the planters of the Sugar Islands. The price of sugar was declining as costs were increasing. The generation of planters born of privilege were not as aggressive in their economic dealings as their forefathers had been and many were more content to spend their fortunes rather than build them. Besides, many had left the Sugar Isles to managers and accountants whilst they went to live the life of aristocrats back in Britain and away from the tumult and climatic conditions of the Caribbean. Years of warfare had seen islands attacked and sacked and the prevalence of hurricanes and the danger of disease were still ever present. 1780, 1784, 1785 and 1786 all saw powerful hurricanes causing widespread destruction to estates and settlements. Added to the traditional dangers was drought on the island of Antigua and a new disease to afflict sugar cane caused by 'cane borers'. 1787 also saw the creation of the 'Society for Effecting the Abolition of the Slave Trade' which would become an increasing thorn in the side of the planters. The power of the West India lobby in Parliament was still substantial, but they would have to divert more time, money and effort in battling the growing abolitionist cause.

Events in France and their consequences in her Caribbean Colonies would provide an unsettling catalyst which would fundamentally change the destiny of the Sugar Islands. The cry of 'Liberty, Egality and Fraternity' were hardly words likely to find favour with the influential planter and slave owner class in the Caribbean. However, the level of expectation raised by these claims would explode in the French colony of Saint Domingue with horrific consequences for her European population. A mulatto revolt was put down in 1790, but a full blown slave rebellion the following year saw the French authorities lose control of the island. 2,000 Europeans were killed, many in a savage and brutal manner. Over 180 sugar factories were destroyed and over 200 plantations were ransacked and burnt to the ground. French revolutionary authorities initially hesitated and were unsure of how to deal with the uprising as their own rhetoric was used against them. Slaves on the island had demonstrated what they were capable of achieving if they could coordinate their numbers against the tiny and often isolated European managers and planters.

Britain formally declared war on France in 1793 and once again the Caribbean became an active battlefield. The British used her Royal Navy to sweep on Martinique, St. Lucia and Guadeloupe. She also sought to take advantage of the chaos in St Domingue and landed an army in Port au Prince to try and take the formally mighty sugar island for herself. In response, the French responded by increasing the stakes. Victor Hugues arrived in the Caribbean proclaiming the emancipation of all black slaves and establishing a slave army. Sowing such revolutionary seeds, the French were able to recapture Guadeloupe and provoke significant rebellions in Grenada and St. Vincent. Another outburst of Maroon activity in Jamaica saw Britain have to divert troops to internal security there once more.

Two Royal Naval expeditions in 1795 and 1796 saw Britain reassert control over St. Vincent, Grenada and St. Lucia and capture the large Spanish island of Trinidad for the first time since the days of Sir Walter Raleigh. But these Caribbean Islands came at a terrible cost as disease once again tore through un-acclimatised European soldiers with horrific efficiency. Some 44,000 British soldiers died in the 1790s. Britain was forced to abandon its seizure of Saint Domingue as its military forces died in their droves. The French tried to reassert their own control, but their calls for emancipation had let the genie out of the bottle and despite concerted attempts they could not return the slaves back inside the bottle. 1804 saw the creation of Haiti as the slave rebellion ultimately created the first freed slave state. This event both inspired other slaves throughout the Caribbean and petrified already nervous planters. Planters sought to yet further tighten slave codes and limit the movement of slaves and brutally punish even the mildest of transgressions in an attempt to assert their authority in a time of war.