|

|

|

|

Thurston had made voyages to India and Australia. An unsuccessful foray in 1853-4 to the goldfields was followed by a return to the sea, first as mate in a Sydney schooner trading to the Pacific islands, next in a brig to Mauritius. Then he a botanical voyage to Rotuma in 1864-5 which ended in shipwreck. Rescued and, bound south for Sydney, he arrived in Fiji again in June 1865, he found the British consul there in need first of a clerk and then of a successor, who would be faced with much more than mere consular duties. Coincidentally, Thurston acquired in Fiji, on 20 July 1867, a wife much older than himself, the formidable, twice-married, Mauritius-born Marie Valette Olsson, nee Prince (d. 1881), with whom he had no children. His second marriage, on 14 January 1883, was to Amelia Murray, nee Berry, with whom he had two daughters and three sons; when it took place he had long justified the nickname, given him by the high chief Ratu Seru Cakobau, of Na Kena Vai 0 the Spearhead, the Very Bayonet. Fiji's hierarchical socio-political structures rendered the archipelago very capable of creating an independent political identity in the eyes of the world, but already the islands were on the verge of becoming a crypto-European colony through the influx of cotton planters.

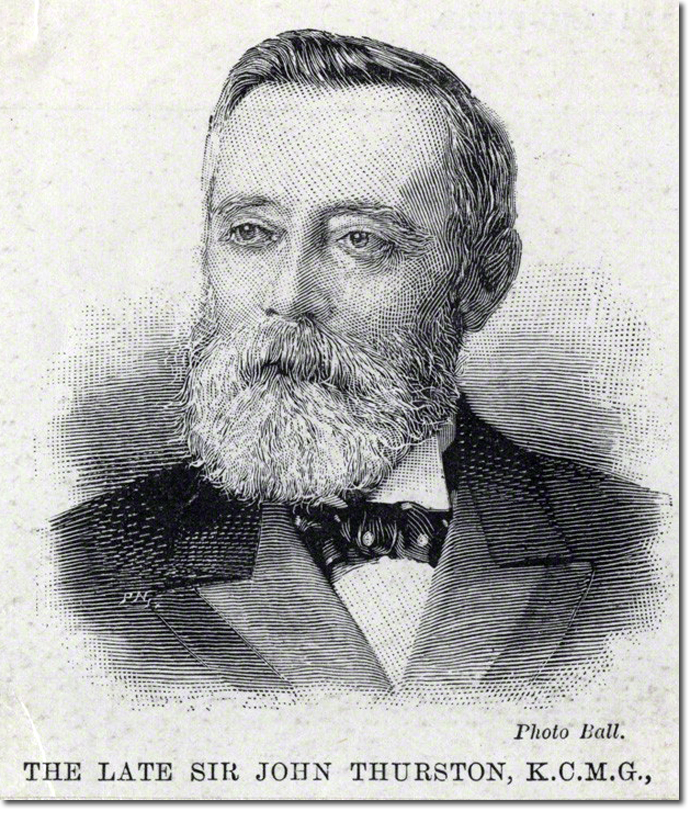

Thurston's opposition to the settlers' argument that all power passed from Fijian chiefs along with the land they were selling to Europeans appeared in the Fiji Times when he was establishing a new plantation himself; and he was actually recruiting labour for it in the New Hebrides, when settlers formed the Cakobau government under the, in their intention, nominal kingship of the vunivalu of Bau, Ratu Seru Cakobau. Thurston joined this government, as a means of averting racial war. He turned the government's focus toward securing Fijian sovereignty and equality before the law. Thurston succeeded in making the first offer of cession in early 1874 a conditional one, with safeguards for Fijians. He made it plain the clause ruling Fijian landownership in the final document of 10 October 1874 would have to be interpreted liberally; and then, by force of character, knowledge, and initially through support of the first governor, Sir Arthur Hamilton Gordon, he startled the local white and adjacent Australasian colonial world by surviving and ruling. Thurston conducted his administration on the principle that Fiji was not a 'white man's country', and neither was the rest of the western Pacific. The necessity of finding more labour than the health of Fijian society would permit for the nascent sugar industry in Fiji made the colony, from 1879, increasingly an Indian country, however, at Gordon's instance; but the main influx of Indian indentured labour took place after Thurston's premature death and, given his view of Fijians' own interests, would never have been countenanced by him. If, through successive international commissions and conferences during the 1880s, he could have made high commission policy binding on France, Germany, and America, too, white settlement and the extension of colonial power in the western Pacific would have stopped with the annexation of Fiji. Fijian self-rule was conducted, with threats of Fijian revolt when it was done otherwise, through a tier of local councils ascending to the boselevuvakaturaga or great chiefly council, which itself always had room for able commoners and in Thurston's day actively encouraged them. In the high commission territories of the western Pacific, sale of alcohol, arms, and dynamite by British subjects to islanders was forbidden, much as labour recruiting for plantations there under no colonial government was restricted; and by the early 1890s, as high commissioner, Thurston would have forbidden all labour recruiting, in islanders' interests, if the French, Germans, and Queenslanders could have been brought to agree. A man short in stature, surrounded by commonly tall Fijians, Thurston was sometimes opprobriously represented by Europeans as an especially great friend to the chiefs, one of whom was his foster son; and he would respond by drawing attention to frequent and savage lectures he read chiefs in government office on their liking for other men's wives or personal attachment to public moneys. His understanding of Fijian societies was not to be lightly challenged; he stood between the indigenous community and exploitation, and without his continued precedence through the 1870s, 1880s, and 1890s Fijians might very well have ended up as subdued as the Maori, whose subordination to white settlers' rule he denounced as an object lesson in bad imperial policy. The well-educated and soldierly twentieth-century Fijian leader Ratu Sir Lala Sukuna, who as a child knew Thurston, looked back to his time as something of a golden age. Men of most races knew there was a power in the western Pacific then--principled, tenacious, uncommonly well informed, and inimitably sardonic. Thurston, who was made a KCMG in 1887, died in harness, at sea, of some form of muscular collapse beyond the diagnostic science of his day, while leaving Fiji for treatment, on 7 February 1897. He was buried on 11 February in the Melbourne general cemetery in what was intended by his foster son Ratu Josefa Lalabalavu to be a temporary grave preparatory to a return to Fiji, which was never to be made. |

Armed Forces | Art and Culture | Articles | Biographies | Colonies | Discussion | Glossary | Home | Library | Links | Map Room | Sources and Media | Science and Technology | Search | Student Zone | Timelines | TV & Film | Wargames