|

|

|

|

Obituary in The Times from August 7th 2011 Terence Gavaghan was a colonial civil servant who came to wider notice for his role during the Mau Mau uprising in 1950s Kenya and the subsequent controversy over compensation. Gavaghan was an Irishman born in India. His 18 years as a district officer and district commissioner (the youngest ever appointed) in colonial Kenya included the time of the Mau Mau Emergency. It was his period of 12 months as the officer in charge of rehabilitation at the Mwea detention camps that remains contentious to this day, with Gavaghan being specifically named by one of the Mau Mau claimants currently suing the British Government in the High Court for compensation for ill treatment. Gavaghan provided two detailed accounts of his experiences at the Mwea. The first was in a volume of autobiography entitled Of Lions and Dung Beetles - or OLAD, as he called it. It covered his time in Kenya, and is remarkable for the detail and richness of his portraits of those he worked with and met: people as varied as Ava Gardner, Elspeth Huxley, Beryl Markham, June Carberry, George and Joy Adamson, Tom Mboya and Jomo Kenyatta. Gavaghan's penchant for keeping records, combined with his formidable memory, makes OLAD a vivid account of distinctive characters and strange events. Every woman's attractiveness and every man's peculiarities are swiftly etched: Gavaghan revelled in the polyglot quirkiness of Kenya's inhabitants, native and colonial, and he deftly recounts marriages, murders and massacres with equal relish. The second account was Corridors of Wire (COW, inevitably): more detailed but lightly fictionalised, though the characters - ranging from Gavaghan himself (renamed Larry Corrigan) to Barbara Castle - are easily recognisable. "Corrigan" recounts "the warping experience of exercising state authorised power over other human beings". In both OLAD and COW Gavaghan's frankness offered many hostages to fortune, upon which critics of colonial policy, and Mau Mau sympathisers, have been quick to seize. Gavaghan had been in a hospital bed, recovering from a ruptured Achilles tendon, when Special Commissioner Carruthers "Monkey" Johnston, with the approval of the Governor of Kenya, Sir Evelyn Baring, invited him in March 1957 to take over the process of unblocking the detention system that had been instituted in 1952. At least 80,000 Kikuyu - one third of the adult males in Kenya's largest tribe - had been rounded up in an effort to break the Mau Mau insurgency, which was overwhelmingly a Kikuyu phenomenon. Tens of thousands had been released, but any further progress towards Kenyan independence was inhibited by the failure of the rehabilitation programme to deal with the last 20,000 detainees, deemed hard-core. Most were held at Manyani, where British authority ruled outside the camp and Mau Mau controlled the inside. Gavaghan, then 35, was seen as a maverick but also as a flamboyant results man. He started at Thiba, one of the Mwea camps, and recruited 200 young loyalist Kikuyu to help to split up the 1,000 detainees there into more manageable groups of 250. Then Gavaghan arranged for batches of detainees from Manyani to be transferred, by train and lorry, to the Mwea. He invited the key ministers in the colonial Government to witness the transfer process and approve it. They did so verbally, and, unbeknown to him, also sought Colonial Office backing for prison regulations to be amended so that "compelling" (but not "punitive") force could be used in these circumstances. Critics of colonial policy have described this as officially approved brutality. Gavaghan and his colleagues at the Mwea fully understood the critique, but felt that the deteriorating situation in the camps - and the imperative of the political timetable - required exceptional measures, even if these sometimes (as he put it in COW) "skirted the edges of the quasi-legal concept of 'compelling force' ". Once order and control had been restored, Gavaghan set about the process of release. He claimed that his tactic was not to seek renunciation of Mau Mau oaths, but simply acknowledgement of oath taking, so as to enable detainees to go back to their homes to prepare for independence. Despite predictions of disaster from Gavaghan's predecessor, aghast at the physical methods being used, it appears that there were no deaths and few serious injuries in the 12 months that it took for Gavaghan to clear the camps of all but a few hundred inmates. The last two hundred detainees were transferred to Hola, where 11 were beaten to death the following year by non-Kikuyu warders: a tragedy Gavaghan condemned, and which almost brought down the Conservative Government. Gavaghan was appointed MBE in 1958, and Baring wrote to him to say how well justified the honour was: "you did an extremely difficult key job admirably". Gavaghan's final postings in Kenya were at Government House itself, rising to acting permanent secretary, where he led the process of Africanising the top 10,000 Civil Service jobs, making sure that former Mau Mau were not excluded. In 1962, a year before Kenya's independence, he was recruited by the United Nations for a mission in Somalia. Thereafter he spent three decades on humanitarian missions, for 12 UN, Irish and voluntary agencies in 17 developing countries, including Libya, Sudan (he was an expert on Darfur), Ethiopia, Uganda, Afghanistan, Indonesia and Tanzania. He gave clandestine assistance to Zimbabwe's African leaders in the years before independence, and also worked for Texaco and Pfizer International on large projects. But it was the year at the Mwea that shaped how others saw him. In retirement Gavaghan became a regular performer at the seminars led by John Lonsdale, director of studies in history at Trinity College, Cambridge, on Mau Mau. He rejected accusations of "brute empiricism" made by other speakers. For him the British role in Kenya had been honourable, and consistent with the Devonshire declaration of 1923, which required the colonial government to act above all in the interests of the native peoples they ruled in Kenya. Gavaghan was born in Allahabad in 1922. His great-grandfather, Patrick, had been a penniless emigrant from Ireland who found work at Hackney railway station. His grandfather, Laurence, had worked on the South India Railways in Madras. His father, Edward, had been orphaned at 5, but the railways and relatives provided a Jesuit education in Sheffield, whence he returned to India as a qualified accountant, eventually becoming Comptroller General in the Indian Civil Service. Edward's early death in turn led to Terence being educated in England, at a Protestant preparatory school and then by the Jesuits at Stonyhurst College. A Harkness Scholarship to the University of St Andrews was followed by a commission in the Royal Ulster Rifles, which was quickly overtaken by the emergence of a vacancy in the Kenyan administration. Gavaghan took pride equally in his Anglo-Indian roots and Irish origins. He married, first, Cecily Tofte in 1948, fathering two sons. After their divorce he married Nicole Goldstein in 1958: and had a son and a daughter. Terence Gavaghan, MBE, colonial administrator, was born on October 1, 1922. He died on August 10, 2011, aged 88 |

|

Obituary in The Irish Times from November 7th 2011 Terence Gavaghan who was born in lndia on October 1st, 1922, was intensely proud of his Irish roots. His great-grandfather, Patrick Gavaghan, emigrated from Co Mayo at the time of the Famine and found work in Hackney Railway Station. Terence's grandfather, Lawrence was sent to work on the South India Railways in Madras and Terence was born in Allahabad. He was educated by the Jesuits at Stonyhurst College in England. A Harkness Scholarship to St Andrews University was followed by a commission in the Royal Ulster Rifles and a post in the Kenyan administration. Terence was possibly best known for his work as a colonial civil ervant at the heart of the Man au controversy. His 18 years as a district officer and district commissioner (the youngest ever appointed) in colonial Kenya included the period of the Mau Mau Emergency. He provided two detailed accounts of his experiences at Mwea camp ( rehabilitation centre). Of Lions and Dung Beetles is remarkable for the detail and richness of his portraits of those he encountered: people as varied as Ava Gardner, Elspeth Huxley, Beryl Markham, June Carberry, George and Joy Adamson, Tom Mboya and Jomo Kenyatta. The other account, Corridors of wire. was more detailed, but lightly fictionalised. With the approval of the Governor of Kenya, Sir Evelyn Baring, Terence was invited in March 1957 to take over the process of unblocking the Mau Mau detention system that had been instituted in 1952. At least 80,000 Kikuyu - one third of the adult males in Kenya's largest tribe - had been rounded up in an effort to break the Mau Mau insurgency, overwhelmingly a Kikuyu phenomenon. When Terence was awarded an MBE in 1958, Baring wrote to him, stating: "You did an extremely difficult key job admirably". He subsequently rose to be Kenya's acting permanent secretary. He led the process of Africanising the top 10,000 civil service jobs, making sure that former Mau Mau were not excluded. In 1962, a year before Kenya's independence, he was recruited by the United Nations for a mission in Somalia. He spent three decades on humanitarian and refugee assignments, for 12 UN, Irish and voluntary agencies in 17 developing countries, including Libya, Sudan (he was an expert on Darfur), Ethiopia, Uganda, Afghanistan, Indonesia and Tanzania. He gave clandestine assistance to Zimbabwe's African leaders in the years before independence, and also worked for Texaco and Pfizer International on major projects. In 1973, the family came to Enniskerry , Co Wicklow, having bought Coolakay Lodge on the old Powerscourt Estate. Terence was delighted to gain Irish citizenship due to his forbears. He joined the Irish United Nations Association and late r ran the Secretariat with his friend John McGarry. The family moved to London in 1987, and in retirement, Terence spoke regularly at seminars concerning the Mau Mau. He rebutted accusations of "brute empiricism" made by other speakers. For him, the British role in Kenya had been honourable. and consistent with the Devonshire Declaration of 1923 which required the colonial government to act above all in the interests of the native peoples they ruled in Kenya. On visits to Kenya in later years, he always felt welcome, whether among former Mau Mau leaders or Kenya government ministers He had two sons, Kevin and Sean, from his first marriage and a third son, David and daughter Sarah, from his second. It could be said that Terence's life straddled the old and the new worlds; he witnessed the twilight of the British empire and the great expansion and work of the United Nations. He was a man of great insight and accuracy; amused by life's foibles, he was always precise, incisive, and often trenchant in his views. An Irish man, and an international man, he will be greatly missed by his friends in Ireland and in the many corners of the world where he advocated change and social justice. He died on August 10th and is survived by his wife, Nicole, his daughter Sarah and sons, Kevin, Sean and David. |

|

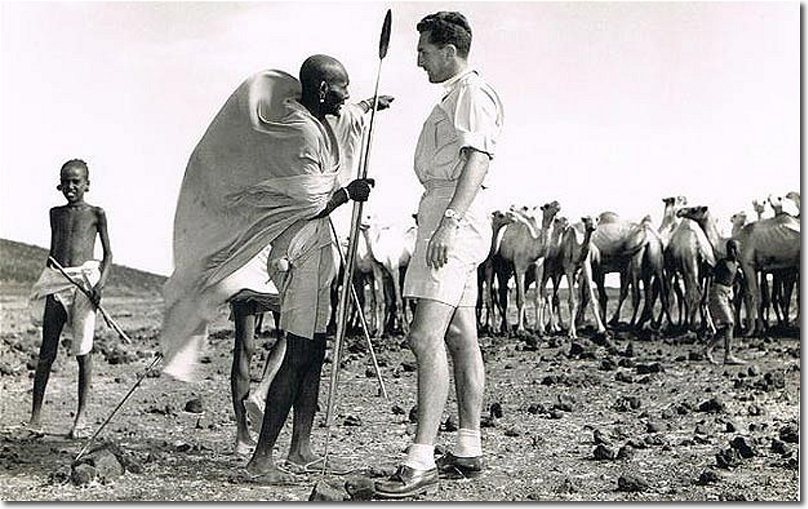

Obituary in Anglo-Somali Journal Autumn 2012 Terence Gavaghan was a longstanding, loyal, and supportive member of the Anglo-Somali Society who appreciated what the Society stood for. Born in India to Irish parents, after education at Stonyhurst and St. Andrews University, Terence's first association with Somali affairs dates from his appointment as DC Mandera in the Northern Frontier District of Kenya in 1946, at the age of23. The district commanded over 200 miles of international boundaries, east and south, and the seasonally nomadic population of his vast territory varied between one and two hundred thousand. They were mainly Somali. The above photograph of a later but unknown date shows Gavaghan with a Samburu tribesman whose people ranged south east of Lake Turkana. As a young District Commissioner he answered to the Provincial Commissioner who happened to be Gerald Reece, later to become, as Sir Gerald, Governor of the Somaliland Protectorate, 1948 - 1953. Issue 32 of this Journal, Autumn 2002, carried an extract from Terence's book Of Lions and Dung Beetles which described the 'trepidation' with which he reported to this 'extraordinary personage' who 'pervaded his life for two years' . He wrote, in his lively style, that 'Reece' s assorted fasces of authority were bound together by his manifest sincerity, deep humanity, love of youth and meticulous attention to detail in a gruelling task. What is more he was as cunning as a cartload of monkeys' . He described Hussein Salad, the Degodia chief and who 'spoke deep and little and had an air of earthy humour. He exuded empathy with glowing, slightly wall-eyes, grizzled spade beard, large metal -trimmed teeth and a loosely furled turban. He was a sturdy, well-planted man, comfortable in himself, pliant tanned pra yer mat over one shoulder, cudgel in hand, striding out with good will'. Issue 34 contained a second extract from Gavaghan's book which described his first safari as DC, a grand tour of his district, some 350 mile s on foot, westwards towards the Moyale District boundary, back south-eastwards above the Wajir border to El Wak, and north again to Mandera. In 2006 Terence supplied Issue 40 of the Journal with politically incorrect doggerel in the form of Northern Frontier DC's 'meeting songs' dating from 1946 - 1947. These made light of the quirks and foibles of many members of the colonial frontier community and may just capture some of the atmosphere of that distant way of life. It was sung of Terence, innocuously enough: 'Now up in Mandera the lorries stay put, 'Cause Gavaghan finds that it's quicker on foot' . The Mau Mau rebellion broke out in 1952 as members of the Kikuyu tribe launched a campaign against the exclusive use of Kenyan land by white settlers. After 11 years as a colonial district officer Terence Gavaghan was recruited, in 1957, after the rebellion had been crushed, to oversee the 'rehabilitation' of Mau Mau prisoners at six camps in central Kenya. Tens of thousands had been released, but further progress had been held back by the continued detention of about 20,000 Kikuyu considered to be the most fanatical. A degree of violence against the prisoners was used under Gavaghan's supervision. In 2011 four elderly Kenyan men sued the British Government for acts of torture carried out during his period in this post.. On 7 April 2011 the High Court in London ruled that the British Government cannot be held legally liable felt abuses during the Mau Mau rebellion. On 18 April 2012 it was announced that secret files covering controversial episodes during the Mau Man uprising once thought lost - were released by the British Government. Terence Gavaghan suffered from Alzheimer's at the very end of his life and was unable to respond to the charges against him. Earlier he had explained that the British had used 'compelling force' because the situation demanded it, but 'punitive force' was never used. He was awarded the MBE for his role. Afterwards he was promoted to Government House where in the run-up to Independence he oversaw the process of Africanising the top 10,000 civil service jobs. In 1962 - 1963 he was engaged by the UN as Chairman of the Administrative Unification Commission of the two recently independent Soma]i states, formerly Somaliland and Somalia He had the good fortune then to encounter Mohamed Ibrahim Egal, Minister of Education, and as Director of Save the Children Fund in Hargeisa attended, in 1993, Egal's inauguration at Borama as President of Somaliland. Between 1963 and retirement in 1987 Terence was contracted as disaster preparedness and relief or government reform adviser for 12 UN, Irish and bilateral voluntary organ isations in 17 developing countries. He also occupied a number of other challenging international positions. In the 1970s he had settled in County Wicklow where he was delighted to gain Irish citizenship. Retirement took him to London from 1987 onwards. In 1948 he married Cecily Tofte with whom he had two sons. After the marriage was dissolved he married Nicole Goldstein in ]958. They had a son and a daughter . The three sons and daughter all survive. |

|

Eulogy by Mervyn Maciel at All Saints, Putney Common, 17.8.11 Farewell To My Dear Friend, Terry Gavaghan God's finger touched him, and he slept. Well, that was Tennyson's euphemistical view on death, and I think it is truly fitting and of great comfort to the family, to see so many here this morning, all come to pay their respects and celebrate the life of a great man- a true friend and colleague, Terence, who was always affectionately known to us as, Terry. Kevin has spoken eloquently about Terence, the husband, father and grandfather, and I feel humbled yet privileged, to have been asked to say a few words about Terry, the man, I've now known for some 20 years. This may come as a surprise to many of you, but although Terence and I worked for the Provincial Administration, our paths in Kenya never crossed. We were to meet, here in London, courtesy of a mutual friend, Monty Brown, who sadly cannot be here today. Terry was a highly intelligent and gregarious man, a gentle giant, not one to suffer fools gladly though, but one who believed in calling a spade a spade. His rise within the service can best be described as meteoric; just think of it - a D.C. at 23, with the enormous responsibilities the job entailed, then, several senior roles within the Provincial Administration, later an Under Secretary for Africanisation in the Cabinet office, then, awarded an M.B.E., and finally with the United Nations in Somaliland where his expertise and experience was greatly valued. With Kenya's independence looming, Terry was also elected President of the first ever Non-racial Senior Civil Service Association- a role he distinguished himself in. In fact, Terry may well have been responsible for my move to the U.K., since, as Under Secretary in the Cabinet office, to him fell the difficult and demanding task of accelerating the pace of Africanisation within the Senior ranks of the Service, a task he accomplished with his customary efficiency, ensuring that our compensation and pension arrangements were safeguarded and guaranteed by Her Majesty's and not the independent Kenya Government, else we might well have ended up with a Zimbabwe-type situation. Terry was a many-talented individual whose achievements it is too difficult to encapsulate in this brief tribute. Suffice it to say that he loved his work and the challenges it offered. He was an avid reader and a brilliant writer. He has two books to his credit - 'Corridors of Wire 'more about events during the State of Emergency in Kenya, and his own brilliantly-written, autobiographical account of his service in colonial Kenya- Of Lions and Dung Beetles. It is unfortunate that he was not able to complete the final book he was so painstakingly working on before the dreadful illness set in. I am certainly going to miss the almost daily telephone calls we exchanged during this period. Anyway, I believe a major portion of the manuscript has been preserved and I hope the family will one day have it published as it will be of great interest to future historians and researchers. Terry was very proud of his family and his Irish roots, and rightly so. He was a very dear friend to the last and showed great interest in others even at a time when his own health was taking its toll. He had many friends the world over with whom he kept in touch. Speaking personally, Terry's exit from our midst is deeply felt not just by me and my wife, but my entire family, and on behalf of us all, and also former colleagues of the Kenya Provincial Administration, I'd like to once again offer our deepest sympathies to Nicole and the whole family over their great loss. Terry was a fighter to the last and bore his illness with great fortitude, and now, if I may, I'd like to pay tribute to Nicole, who has stood by Terry all these years and especially during the difficult months of his illness. Seeing her cope, almost single-handedly, I can honestly say she has more than the patience of Job and I am sure Terry appreciated all the love and kindness shown to him by her, his children and grandchildren. There is so much more I'd like to say, but I just can't forget his persistent efforts in ensuring that I was granted membership of the Kenya Administration Club here in the U.K., and can I now close by quoting from KAHLIL GIBRAN'S - The Prophet: "For what is it to die but to stand naked in the wind and to melt into the sun? And what is it to cease breathing, but to free the breath from its restless tides that it may rise and expand and seek God unencumbered?" Terry, my dear friend, KWAHERI YA KUONANA (Till we meet again). Mervyn Maciel |

Armed Forces | Art and Culture | Articles | Biographies | Colonies | Discussion | Glossary | Home | Library | Links | Map Room | Sources and Media | Science and Technology | Search | Student Zone | Timelines | TV & Film | Wargames