|

|

|

|

Sir James Brooke was born at Secrore, a suburb of Benares, India, on 29 April 1803, the second son of Thomas Brooke, chief judge of the East India Company's court at Moorshabad, and his Scottish second wife, Anna Maria (nee Stuart). He remained in India until the age of twelve when he was sent to stay with his paternal grandmother in Reigate. His only formal schooling was as a boarder at Norwich grammar school, which he hated and ran away from after two or three years. When his parents returned to live in Bath, he joined them there and was placed under the charge of a hapless tutor. He was a spoiled child, shy but wilful. On 11 May 1819, aged sixteen, he entered the service of the East India Company as an ensign attached to the 2/6th regiment Bengal native infantry, and transferred to 18th native infantry in 1824. Promoted lieutenant in August 1821 and sub-assistant commissary-general in May 1822, he commanded a troop of irregular cavalry in the First Anglo-Burmese War and was seriously wounded in one lung during an action at Rangpur, Assam, on 27 January 1825. He was awarded a wound pension of 70 pounds per annum. There is no truth in the often-repeated story that the wound he suffered in Burma was to the genitals, and it may be significant that during his long recuperation at Bath he was briefly engaged, possibly to the daughter of a Bath clergyman.

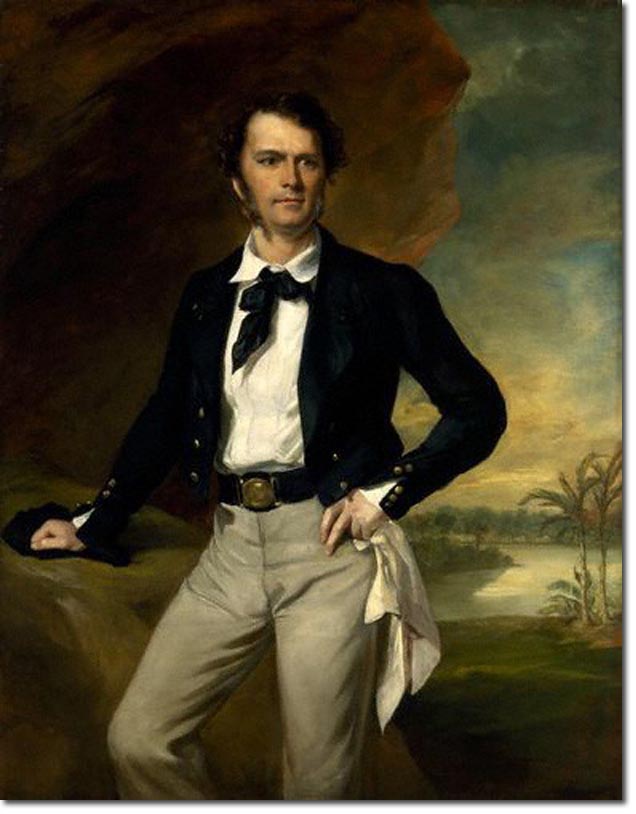

Unable to reach India before the expiry of his five years' leave, Brooke resigned his commission and returned home in 1831 on the Castle Huntley after visiting China, Penang, Malacca, and Singapore. Presumably about then he had the idea of exploring the Indian archipelago. In 1834 he purchased a brig, the Findlay, and made an unsuccessful trading voyage to China. There was reason now to accept what his father had told him earlier: 'about trade you are quite ignorant, and ... there is no pursuit for which you are less suited' After his father died on 12 December 1835, leaving him an unencumbered 30,000 pounds, Brooke purchased a schooner of 142 tons which he named the Royalist. After a practice voyage in the Mediterranean in late 1836, he sailed on 16 December 1838 for Singapore. In October 1838 he had published a prospectus of his voyage, reflecting the influence of George Windsor Earl's The Eastern Seas (1837) and indicating his desire to counter Dutch influence in those areas of the eastern archipelago not divided into clear spheres of influence by the Anglo-Dutch treaty of 1824. His primary focus of interest was Marudu Bay in what is now Sabah, which he saw as one of a string of British settlements linking Singapore with Port Essington in northern Australia. He saw himself as taking up the mantle of Alexander Dalrymple (1737-1808), hydrographer, and Sir Stamford Raffles (1781-1826), the founder of Singapore. The Royalist was armed--with six 6-pounders and swivels, flew the white ensign of the Royal Yacht Squadron, and so resembled a small warship. In Singapore Brooke learned that the profitable antimony trade with Sarawak had been disrupted by a local rebellion against the sultan of Brunei, who exercised sovereignty there in the form of tax-collecting. Entrusted by Governor Bonham of Singapore with the mission of thanking the sultan of Brunei's uncle, Raja Muda Hassim, for his assistance to some shipwrecked British sailors, Brooke was given a warm reception by Hassim when he reached Kuching, the capital, on 15 August 1839. He also received full details of the rebellion which Hassim had been sent to quell when governor Pengiran Mahkota's half-hearted efforts had been unsuccessful. After investigating the coast and visiting the Samarahan and Lundu rivers, where he met the Malays and the Sebuyau Dayaks, he spent the next six months in the Celebes visiting the Bugis kingdoms of Waju and Boni, where he impressed the people with his horsemanship and his accuracy as a marksman. However, he saw no future for himself there. After a brief spell in Singapore, Brooke returned to Kuching on 29 August 1840 and immediately became embroiled in suppressing the rebellion. With the assistance of his ship's crew, he led Hassim's forces in a rout of the rebel headquarters at Belidah on the Sarawak River. He also interceded with Hassim to spare the lives of the local Malay chiefs who had led the Bidayuh antimony miners in their opposition to Brunei authority. In return for his assistance against the rebels, Hassim had promised Brooke the governorship of Sarawak, a promise Brooke enforced on 24 September 1841 when the Royalist's guns were trained on Hassim's palace. In July 1842 he obtained personal confirmation of his appointment from Sultan Omar Ali of Brunei, and on 18 August 1842 was installed as raja at Kuching in the face of clear hostility from Pengiran Mahkota and his supporters. After the return of Hassim, Mahkota, and their retainers to Brunei, Brooke enlisted the assistance of the Royal Navy in having Hassim installed as the sultan's chief minister in October 1843. Having secured his sovereign status, Brooke appointed Henry Wise as his London agent to lobby the British government for recognition and to interest potential investors. However, Wise's interest was in forming a large company to exploit Sarawak's much vaunted mineral resources, but Brooke found him impatient and heedless of native interests. In 1848 Wise founded the Eastern Archipelago Company to exploit Sarawak and Labuan, but by the end of that year the two men had fallen out over Wise's unwise financial advice and his unauthorized granting of an antimony concession in Sarawak. In Wise, the raja had made a dangerous enemy. Influenced by Raffles's History of Java, Brooke saw himself as reforming and restoring the corrupt and declining ancient Malay kingdom of Brunei. In Edward Said's terms, he was a romantic 'orientalist'. The code of laws he introduced in Sarawak was based on that of Brunei, tempered by British notions of 'fair play'. Islam was to be respected and Malay was to be the language of government. At the same time Brooke was committed to abolishing practices that offended liberal humanitarian views, such as forced trading, amputation, slavery, and head-hunting. Using the hereditary Malay elite as a second level of authority under his bevy of hand-picked young European officers, he fostered a form of highly personal government consisting largely of the adjudication of disputes and offering the least line of resistance to traditional practices. The polyglot peoples of Sarawak came to refer to it as perentah (law and order) rather than kerajaan (hierarchically organized power). Brooke's idealistic and reformist stance was transformed by the exercise of power and the constant need to defend it. The raj the man set out to make ended up making the man. Nevertheless, he continued to claim that his government was acting on behalf of native interests, and it was this tradition which continued to be the informing ideology of Brooke rule. Brooke's ability to inspire loyalty and affection among his officers also established a tradition of altruistic service. His economic policy was based on free trade and hostility to middlemen and speculators. Nevertheless his taxation was partly based on monopolies. The indigenous population was lightly taxed, and a large proportion of taxation was from the Chinese community, through the farming of the government monopolies of opium, gambling, and arrack. In 1859 the monopolies contributed 64 per cent of the revenue collected, though normally the proportion was lower. The territory originally secured by Brooke in July 1842, known at that time as Sarawak Proper, consisted of what is now the first division, the territory from the Samarahan River in the east to Tanjong Datu in the west and inland to the mountain watershed. The remainder of what is now the Malaysian state of Sarawak was under the loose overlordship of the sultan of Brunei and his tax-collectors, including a number of part-Arab sherif who formed alliances with Dayak chiefs in coastal raiding as far as Sumatra. Brooke quickly became involved in putting down this raiding, enlisting the assistance of the Royal Navy through his friendship with Captain Henry Keppel (1809-1904) of HMS Dido, whom he met in Penang in early 1843. In June 1843 and again in August 1844 Brooke and Keppel joined forces to attack and destroy the principal Dayak longhouses of the Batang Lupar and Saribas River systems, also putting to flight his principal political opponents, Sherif Sahap and Sherif Mullah, and capturing Pengiran Mahkota. During the second expedition Dayaks under the command of Rentap killed one British officer and the senior Malay chief, Datu Patinggi Ali. However, these events gave the raja effective control over what is now the 2nd division, and this was to be formalized by treaty with the sultan of Brunei in 1853. Much of his success was due to his exploitation of the Sebuyau and Balau Dayaks' enmity towards the other Dayak tribes and their perception of him as their protector. The destruction of the pirate base at Marudu by Admiral Sir Thomas Cochrane's fleet in August 1845 meant that coastal raiding by the Illanun of the southern Philippines had been dealt a heavy blow. However, early in 1846 Hassim and Brooke's other allies in Brunei were murdered at the sultan's behest, seriously threatening his plans to reform and manipulate the sultanate to his advantage. In August he accompanied Cochrane on a punitive expedition to Brunei, resulting in the capture of the town and the sultan's cession to Britain of the nearby island of Labuan, which Brooke saw as a strategic base for British shipping and trade. On his return to England in October 1847 Brooke was greeted as a hero and lionized by high society. Made an Oxford DCL in November 1847 and a KCB in April 1848, and with his portrait painted by Sir Francis Grant RA, he quickly became one of the icons of early Victorian imperialism. The publication of his edited Borneo and Celebes journals by Keppel in early 1846 and articles in the Illustrated London News had also done much to publicize him. Appointed governor of the new colony of Labuan (November 1847 to February 1856) and consul-general for Borneo (July 1847 to August 1855), he nevertheless found it difficult to obtain recognition from the British government of his sovereign status in Sarawak. Eventually he claimed that his authority was derived not from the sultan of Brunei's cession of power to him but from the senior Malay chiefs who collectively conferred it upon him after their rebellion against Brunei. In this spirit he established in 1855 an advisory supreme council with Malay and European representation to meet once a year. From 1841 Brooke was assisted by a Eurasian interpreter, Thomas Williamson, and then by the botanical collector Hugh Low (1824-1905). From 1848 he was assisted and advised by his private secretary, Spenser St John (1825-1910), whose political skills proved invaluable and who later wrote a biography of Brooke. Continuing his campaign against Dayak raiding, Brooke arranged for Captain Arthur Farquhar's ships to attack the Dayaks of the Saribas once again, resulting in the battle of Beting Marau at the mouth of the Saribas on 31 July 1849, when more than 1000 Dayaks were killed. He also initiated a system of erecting forts on the principal rivers to control the movement of Dayaks and institute a system of government. The first to be built were at Kanowit, Skrang, and Lundu, where his younger nephew, Charles Anthoni Johnson Brooke (1829-1917), was to be posted on his arrival in 1852. In the meantime he had also encouraged the establishment of an Anglican mission as a means of pacifying the Dayaks in up-river areas. In 1848 the Revd F. T. McDougall and his wife, Harriette, had arrived to head the Borneo mission, establishing a church and a school in Kuching and subsequently organizing a network of mission outposts. In the same year arrived Captain John Brooke Johnson (d. 1868, aged forty-five), who in 1848 took the surname Brooke, and was known as Brooke Brooke, the raja's elder nephew, who was to be trained in government in the expectation of succeeding his uncle. Although Brooke's duties as governor of Labuan were not very demanding, he was dispatched by the British government in his capacity as consul to Siam in August 1850 to negotiate a new commercial treaty. For once, however, his diplomatic skills were unequal to the task. He was unable to obtain an audience with the king or his chief minister and had to conduct negotiations by letter. When these failed, he foolishly threatened to use the Royal Navy to enforce his requests. The large sums of prize money claimed through the Singapore naval court by Sir Thomas Cochrane for his action against Illanun raiders and Captain Farquhar for his part at Beting Marau were brought to the attention of parliament and the British public by the radical politicians Richard Cobden--who wrote of Brooke's 'powers of evil' - and Joseph Hume in 1850, eventually resulting in Lord Aberdeen's appointment of a commission of inquiry in Singapore in 1854. Wise was instrumental in providing much of the damaging evidence. Although Brooke was exonerated of charges of inhumanity and illegality, the experience was humiliating and embittering. Moreover, he had contracted smallpox in May 1853, and the resultant scarring and other complications seem to have caused him serious psychological damage. Contemporaries noted that he was never the same afterwards. Deprived of vital support from the Royal Navy, Brooke's weakened political position was revealed in February 1857 when the 4000 Hakka Chinese goldminers of the Bau gongsi (co-operative), led by Liu Shanbang, defied the authority of his magistrates and tax-collectors and descended in force on Kuching to establish a government more sympathetic to their cherished autonomy. In the resulting affray the raja narrowly escaped with his life, and the defeat of the rebels was largely the work of the Borneo Company's steamer and Charles Brooke and his Dayak forces from Lingga. Many hundred Chinese were subsequently killed in their attempt to flee across the border into Dutch Borneo, and some of their heads smoked in the Kuching bazaar. In 1856 the Borneo Company Ltd had begun operations as the only public company allowed to function in Sarawak. The raja's intention was that it should take over the monopoly of the coal, antimony, sago, and gutta-percha trades and assist the government financially in its own schemes. In the wake of the rebellion he borrowed 5000 pounds from the company for reconstruction, but was furious when it soon called for repayment. The company's coalmine at Sadong had been a costly failure, and the rebellion had resulted in a dearth of Chinese labour for other projects. The debt was eventually paid off by Baroness Burdett-Coutts (1814-1906), the philanthropic millionairess whom the raja had first met in 1848 and who now became his patron and financier. Financial and other anxieties may have prompted the paralytic stroke the raja suffered in England on 21 October 1858. One heartbreaking casualty of the rebellion had been the raja's house in Kuching and his extensive library. Largely self-educated, Brooke was widely read in literature and theology and liked to hold court with his intellectual inferiors. Much of his undoubted attraction can be attributed to his erudition and eloquence, but he was essentially an autodidact and a dilettante. A Unitarian by religious persuasion, he was inclined to tease the Anglican bishop and anyone else of orthodox views. Maintaining an interest in natural history, he encouraged the work of Alfred Russel Wallace (1823-1913) and allowed him to use a house at Santubong to write his famous paper on evolution (1855). Brooke's reverses, together with his failure to obtain recognition from the British government and his indebtedness after 1857, led him to offer Sarawak for sale to several European governments in order to recoup his investment. He also stunned his family in 1858 by acknowledging a stable-hand, Reuben George Walker (died May 1874, reportedly aged forty, when the ship British Admiral was lost at sea) as his illegitimate son and announcing his intention of taking him out to Sarawak. Whether Reuben was his son, or recognition was to conceal a homosexual relationship, must remain a matter for speculation. The raja was fond of young boys and never married, but early Victorian male behaviour can easily be misinterpreted by later generations. For example, his biographer, Spenser St John, was strongly advised by a friend in 1878 to remove a reference to his kissing the raja on his deathbed as 'too sensational Nelsonic' and likely to cause offence. The most serious consequence of Brooke's acknowledgement of Reuben and his foreign negotiations was the alienation of his elder nephew, Brooke Brooke, who administered the government during the raja's increasingly extended absences. He saw Reuben as a serious challenge to his inheritance and his uncle as wanting to sell it off. Events came to a head in Singapore in January 1863 when the raja both disinherited and banished Brooke Brooke for defying his authority. After establishing Charles in his place, the raja left Sarawak for the last time on 25 September and returned to England. By this time the British government had finally recognized Sarawak as an independent state, but its finances were still underwritten by Baroness Burdett-Coutts, whom he named as his heir. His close friendship with the eccentric baroness and her companion, Mrs Brown, is another relationship capable of interpretation. He seems to have been a man who was 'able to be the close and intimate friends of women without a tinge of love-making'. The raja's last strategic success in Sarawak had been formally to acquire from the sultan of Brunei in 1862 the Melanau-peopled, sago-producing areas of Muka and Oya to the north of the Rejang River estuary, together with a vast inland area to the Dutch border. The declining demand for antimony and the failure to discover anticipated gold and diamonds had left Sarawak without a staple export. Monopolization of the sago trade with Singapore offered an attractive source of export revenue, and this had been secured in an armed expedition led by his two nephews against Pengiran Nipa of Muka in 1860. The expedition also disposed of the raja's principal political enemy, the formidable Sherif Masahor, who had been suspected of planning a general native uprising (known as the Malay plot) against the raja and the Dutch for some years. On his retirement to Burrator, a house he bought following a public subscription in 1859 on the edge of Dartmoor, near the isolated village of Sheepstor in Devon, James lived out his last years in rural seclusion, and was a churchwarden at Sheepstor. Nevertheless, he continued to press the British government to take over Sarawak and to negotiate with foreign governments. Baroness Burdett-Coutts gave up her rights in 1865, enabling James to declare Charles his heir. He achieved some reconciliation with members of his family and former officers alienated by his disinheritance of Brooke Brooke, but did nothing to assist him and his son, Hope Brooke. This contrasted with his generosity towards Reuben and the sons of his Eurasian half-brother, Charles William Brooke, the son of Thomas Brooke and an Indian woman before his marriage to Anna Maria. Charles William had been brought up with the second family, and both James and his sister Emma maintained an affectionate relationship with him. In 1866 Brooke suffered his second stroke, and on 11 June 1868 he died at Burrator after suffering a third stroke two days earlier. He was buried on 17 June at Sheepstor churchyard, Devon. He was commemorated by the Brooke memorial opposite the old court house in Kuching, Sarawak. He was succeeded as raja by his nephew Sir Charles Anthoni Johnson Brooke (1829-1917). Brooke's was a remarkable achievement. A Victorian imperial hero, yet controversial and loathed by some, he founded a state and established a regime which lasted a century, and also influenced the fiction of Kipling, Conrad, and lesser writers. His Sarawak achievement won him fame but no vast fortune: the English probate value of his estate was under 1000 pounds. By R Reece Read a Review of White Rajah: A Biography of Sir James Brooke |

Empire in Your Backyard: Plymouth Article | Significant Individuals

Armed Forces | Art and Culture | Articles | Biographies | Colonies | Discussion | Glossary | Home | Library | Links | Map Room | Sources and Media | Science and Technology | Search | Student Zone | Timelines | TV & Film | Wargames