|

|

|

|

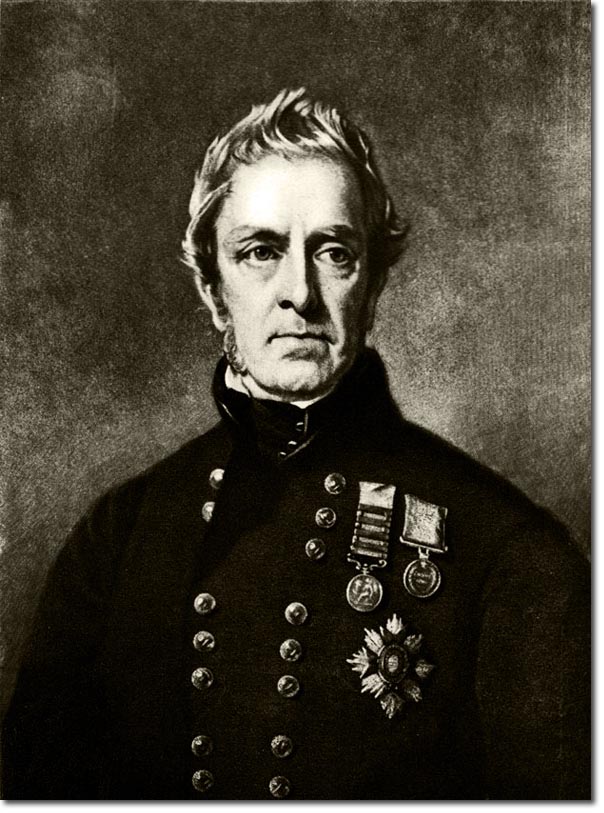

Major General George Pollock was one of the men tasked with cleaning up the mess in the aftermath of the destruction of Elphinstone's army. There were still British hostages being held captive by Akbar Khan, and British garrisons were being besieged in Afghanistan. Troops were gradually collected at Peshawar, and Pollock was selected in January 1842 to command, with political powers, the expedition for the relief of Sir Robert Sale's force, besieged at Jalalabad. Pollock reached Peshawar on 5 February. Brigadier Wild's brigade had been defeated in the Khyber and retreated in disorder. At Peshawar the sepoys' morale was low--some were mutinous and many were sick in hospital, and some of the officers were defeatist. Pollock patiently stayed two months, awaiting reinforcements, improving morale, and preparing his offensive. After the sickness had subsided and reinforcements, including much-needed European troops, had arrived, Pollock preferred to face hostile criticism on his delay to acting before his force was ready, urgent as he understood the situation at Jalalabad to be. On 31 March he advanced with his column to Jamrud. He had reduced his army baggage to a minimum, and himself shared a tent with two officers of his staff. He had conciliated his Sikh allies, and inspired his own sepoys with some confidence.

On 5 April Pollock advanced to the mouth of the Khyber Pass, where the Afridis had made a formidable barrier in the valley, had taken up strong positions, and had erected redoubts on the high ground to the right and left of the pass. Pollock had made all his arrangements with care. He directed columns under Lieutenant-Colonel Taylor and Major Anderson to crown the heights on the right of the pass, while similar columns under Lieutenant-Colonel Moseley and Major Huish crowned the hills on the left. Artillery and the infantry of the advance guard were drawn up opposite the pass, and the cavalry placed to counter any attack from the low hills on the right. The heights on each side were scaled and crowned, despite determined opposition. Finding their position turned, the enemy abandoned the barrier at the mouth of the pass and the redoubts on the heights, and Pollock's main body began to destroy the barrier. The flank columns descended and attacked the enemy, drawn up in dense masses, and despite a vigorous defence forced them to retreat. Pollock pushed on to Ali Masjid (some 5 miles into the pass); it had been evacuated, and was at once occupied. Detained there during 6 April by finding the Sikhs had not completed the arrangements for guarding the road to Peshawar, Pollock marched on the 7th to Ghari Lala Beg, meeting little opposition on the road, then pushed on to Landikhana and to Dakka, and emerged on the other side of the pass. Pollock's was the first army ever to successfully fight its way through the Khyber. He camped near Lalpura, where Sadut Khan was driven off, and on the 16th Pollock arrived at Jalalabad, the band of the 13th regiment marching out to play the relieving force into the town. Sale's 'illustrious garrison' had sallied out on 7 April, and, though outnumbered had decisively defeated Akbar Khan, capturing his guns and burning his camp. The whig Lord Auckland had been replaced as governor-general by the tory Lord Ellenborough, appointed by the incoming prime minister, Peel, at the end of February 1842, and on 15 March Ellenborough sent a spirited letter to the commander-in-chief in India, advocating not only the relief of the troops at Jalalabad, Ghazni, Kalat-i-Ghilzai, and Kandahar but the advantage of striking a decisive blow at the Afghans, and possibly reoccupying Kabul and recovering the British captives before withdrawing from the country. Yet the news of Sale's victory at Jalalabad and of Pollock's forcing of the Khyber and arrival at Jalalabad was for Ellenborough outweighed by the news of the capitulation of Ghazni by Colonel Palmer, and of Brigadier-General Richard England's repulse on 28 March at Haikalzai, and he ordered Pollock at Jalalabad and Major-General Sir William Nott at Kandahar to arrange the withdrawal of all British troops from Afghanistan. However, neither Pollock nor Nott feared responsibility, and both believed an advance on Kabul must be made before withdrawing. Pollock communicated with Nott, requesting him not to retire until he heard again from him. Pollock protested against Ellenborough's policy and argued the necessity of advancing, if only to recover the captives, while at that season it was highly advantageous for the health of the troops to move to a hotter climate rather than retire with insufficient carriage through the pass to Peshawar. He further assumed that the instruction left him discretionary powers. Having received orders from Ellenborough that, for the troops' health, they would not be withdrawn from Afghanistan until October or November, Pollock remained at Jalalabad negotiating with Akbar Khan for the release of the captives and preparing to advance on Kabul. Apparently influenced by political officers, he hoped to set up a government under British influence, 'salvaging something from the Afghan buffer strategy' (Yapp, 434), negotiated with various Afghan groups, but failed. On 2 August captains Troup and George Lawrence arrived from Kabul, deputed by Akbar Khan to conclude negotiations, but had to return to captivity as Pollock refused to retire. Ellenborough, chagrined at the generals' evading his orders to withdraw, wrote to Peel in early June that 'Major Generals Nott and Pollock have not a grain of military talent' In July, Ellenborough decided to leave the responsibility for an advance on Kabul (or, as he put it, a withdrawal by way of Kabul) to the discretion of Pollock and Nott, directing Pollock to combine his movements with those of Nott should he decide to retire by Ghazni and Kabul; in that case, as soon as Nott advanced beyond Kabul, Pollock was directed to issue such orders to Nott as he might deem fit. There followed a race between the two generals to reach Kabul first. In the middle of August Pollock heard from Nott that he would withdraw a part of his force by way of Kabul and Jalalabad, and on 20 August Pollock moved with about 8000 men towards Gandamak, leaving a detachment to hold Jalalabad. Pollock and Nott's 'army of retribution' was on a punitive expedition to avenge Afghan treachery and atrocities. Pollock's force advanced along the line of Elphinstone's retreat, past looted and mutilated corpses and carrion-picked skeletons. At Tezin they found a pile of 1500 corpses of sepoys and camp followers who had been stripped naked and left to die in the snow. In reprisals the troops burned villages, destroyed crops, felled trees, and slaughtered or drove off animals. Pollock reached Gandamak on the 23rd, and on the 24th he attacked the enemy and drove them out of their positions at Mamu Khel and Kuchli Khel, and then out of the village and their adjoining camp. Major George Broadfoot and his sappers distinguished themselves, and captured the enemy's tents, cattle, and much ammunition. The Afghans fled to the hills; the heights were attacked, and position after position carried at the point of the bayonet. Having dispersed the enemy and punished the villagers of Mamu Khel, Pollock collected supplies at Gandamak and prepared for the advance on Kabul. Leaving a strong detachment at Gandamak, Pollock advanced on 7 September in two divisions, the first, which he himself accompanied, under the immediate command of Sir Robert Sale, the second under Major-General McCaskill. Pollock encountered the enemy on the 8th when advancing on the Jagdalak Pass. The enemy position was very strong and difficult to approach. The hills on each side were studded with sangars (stone breastworks) and formed an amphitheatre inclining towards the left of the road. After shelling the sangars Sale dispersed the enemy and Pollock pushed on, rejecting Sale's advice to rest the men and spare the transport animals. He decided to give the enemy no time to rally, even at the cost of some of the animals. Captain Troup, then a captive at Kabul, subsequently told Pollock that, had he not pushed on, Akbar Khan would have sallied out of Kabul with 20,000 men. Pollock reached Seh Baba on the 10th, and Tezin on 11 September, and was joined on the same day by the 2nd division. Akbar Khan had sent the captives to Bamian and, learning that Pollock had halted at Tezin, decided to attack him there. He opened fire in the afternoon of 12 September. Pollock immediately attacked the enemy, some 500 of whom were along the crest and upon the summit of a range of steep hills running from the northward into the Tezin valley. They were taken by surprise, and driven headlong down the hills. Fighting was suspended by dusk. At dawn preparations were made for forcing the formidable Tezin Pass, some 4 miles in length. The Afghans, numbering some 20,000, had occupied every height and crag not already crowned by the British. Sale, with whom was Pollock, commanded the advance guard. The enemy were driven from post to post, contesting every step, but overcome by repeated bayonet charges. At length Pollock gained complete possession of the pass; but the fight was not over. The Afghans retired to the Haft Kotal, an almost impregnable position on high hills, and the last they could hope to defend in front of Kabul. But Pollock's force had now become accustomed to victory, and was burning to avenge the disaster that had befallen Elphinstone's army near the same spot. The Haft Kotal was at length surmounted and the enemy driven from crag to crag. Pollock, having thus completely dispersed the enemy, on 12 and 13 September continued his march. The passage through the Khurd Kabul Pass was unmolested, but the scene was painful, for the skeletons of Elphinstone's force lay so thick that they had to be dragged aside to allow the guns to pass. Butkhah was reached on the 14th, and on the 15th the force camped near Kabul. The British flag was hoisted with great ceremony in the Bala Hissar, Kabul, on the morning of the 16th. Akbar Khan, who had commanded the Afghans in person at Tezin, fled to the Ghorebund valley. Next day Nott arrived from Kandahar and camped at Arghandeh, near Kabul. The armies of Nott and Pollock were camped on opposite sides of Kabul (Nott having moved his camp to Kalat-i-Sultan), and Pollock assumed command of the whole force. On arrival at Kabul Pollock sent his military secretary Sir Richmond Shakespear with 700 Kazlbash horsemen to Bamian to rescue the captives, and on 17 September he requested Nott to support Shakespear by sending a brigade in the direction of Bamian. Nott, resenting Pollock's victory in the race to Kabul, objected, saying his men required rest, and excused himself from visiting Pollock on the plea of ill health. Pollock, whose amiability was never in doubt, went on the 17th to see Nott, and, finding that he was still indisposed to send a brigade, ordered Sale to take a brigade from his Jalalabad troops to support Shakespear. The captives had, however, by bribes bought their own freedom, met Shakespear on the 17th, and arrived at Pollock's camp on 22 September. Pollock ascertained that Amir Ullah Khan, one of the fiercest opponents of the British in Afghanistan, was collecting the scattered remnant of Akbar's forces in the Kohistan or highlands of Kabul. He therefore sent a strong force, taken from his own and Nott's division, under McCaskill, whose operations were completely successful. The fortified town of Istalif was carried by assault, and Amir Ullah forced to flee. Charikar and other fortified places were destroyed, and the force returned to Kabul on 7 October. To 'inflict just, but not vindictive retribution on the Afghans', on 9 October, Pollock instructed his chief engineer, Captain Frederick Abbott, to demolish the famous old Char Chutter (or four bazaars), where the head and mutilated corpse of Sir William Macnaghten had been displayed. On 12 October, Pollock started for India. He took as trophies forty-four pieces of ordnance and a large quantity of warlike stores, but, for want of transport, had to destroy the guns en route. He also took some 2000 Indians, sepoys, and camp followers of Elphinstone's army who had been found in Kabul. Pollock, with the advance guard under Sale, reached Gandamak on 18 October with little opposition; but McCaskill had some fighting, and the rear column under Nott was engaged in a severe action in the Haft Kotal. On the 22nd the main column arrived at Jalalabad, McCaskill arriving on the 23rd and Nott on the 24th. On 27 October the army began to move from Jalalabad, having destroyed the fortifications and town. Pollock reached Dakka on the 30th, and Ali Masjid on 12 November. Having during his entire march exercised the greatest caution, he met with no difficulty in any of the passes. McCaskill's division met with much opposition in the Khyber, and suffered severely. His 3rd brigade, under Wild, was overtaken at night in the defiles leading to Ali Masjid, and lost some officers and men. Nott arrived at Jamrud with the rear division on 6 November. The whole army camped some 4 miles from Peshawar. On 12 November it moved from Peshawar and, crossing the Punjab, arrived after an uneventful march on the banks of the Sutlej, opposite Ferozepore. Here they were met by Ellenborough and the commander-in-chief, who, with the army of reserve, welcomed them with ostentatious pomp. On 17 December Sale, at the head of the Jalalabad garrison, crossed the bridge of boats over the Sutlej into Ferozepore. On the 19th Pollock crossed and was received by Ellenborough, and on the 23rd Nott arrived. Banquets and fetes were held. Raja Shen Singh presented to Pollock, through the governor-general, a sword of honour. Pollock was made a GCB (2 December 1842) and given the command of the Dinapore division. The thanks of both houses of parliament were voted to Pollock, and Peel praised his services. However, Pollock and his friends believed he had been unjustly under-rewarded. He wrote that this was 'owing to the difference regarding my unauthorized advance to Cabul ... as the Government did not wish to act contrary to the opinion of the Governor General'. In December 1843 Nott, who had been appointed political resident at Lucknow, resigned on account of ill health, and Pollock became acting resident until September 1844, when he was appointed military member of the supreme council of India. The Calcutta British subscribed a fund to honour Pollock by establishing the Pollock gold medal, bearing his portrait, to be awarded to the best candidate at the East India Company's military college, Addiscombe, on each examination for commissions. Following Addiscombe's closure, from 1861 it was awarded at the Royal Military Academy, Woolwich, though to economize the medal's size and value were reduced, which Pollock resented. Pollock was compelled to resign his appointment and leave India in 1846 due to serious illness. |

First Afghan War | Significant Individuals

Armed Forces | Art and Culture | Articles | Biographies | Colonies | Discussion | Glossary | Home | Library | Links | Map Room | Sources and Media | Science and Technology | Search | Student Zone | Timelines | TV & Film | Wargames