|

Review of Volume 1: Beyond the Cape: Sin, Saints, Slaves, and Settlers

|

|

Beyond the Cape is Braz Menezes' first book in his Matata Trilogy. The three books are technically historical fiction but they are very much set in a believable world telling the story of a Goan family's experience spanning both sides of the Indian Ocean from the 1920s until decolonisation and beyond. Ostensibly it tells the story of Lando, who in this book is a young boy growing up in Kenya. In reality, the story uses Lando's actual life very much as a microcosm of a typical experience that any number of Goans might have lived through at the tail end of empires (as both the Portuguese and the British Empire have a role to play in this story). It also follows various branches of Lando's family tree to allow the story to move back in time or across the vast geographical spaces inhabited by the diffuse Goan diaspora. The title of 'Beyond the Cape' is chosen well as the fictional account is also book-ended by an introduction and a concluding author's note that puts a historical context to the story contained within these chapters. The historical explanation helps explain why the front cover sports a painting of a fifteenth century Portuguese Caravel plunging through dangerous seas. It also explains the role of Catholicism to the story and the reasons why certain parts of the world were more familiar to the Goan community than others. This historical context is by no means exhaustive and the fictional account itself reveals far more history than you might expect from a book with a historical fiction label. I know that the vast majority of the events described in this book are taken very much from actual events and often including the real names of the people involved and described in the places that they actually took place. The device of using a fictional family to thread these historical events together is one that has to be used with care but in the right hands it can allow an author the ability to impart more than just bare facts and information. It can also give the author the ability to give texture to what might otherwise be an all too dry or all too familiar account. A skilled author can allow the reader to feel what it might have been like to have lived this particular life, in this particular place, within a particular community and in a particular era. He might allow the reader to sense the smells, sights, sounds and experience or empathise with what life might have been like for these people at this point in time. He can introduce subtleties, emotions and nuances that a work of non-fiction would be unable to convey. However, the author must also be careful not to romanticise, embellish or glorify his account. An author of historical fiction gives himself some freedom and latitude to explain certain events but he also gains responsibilities to ensure that he stays faithful to events as they occurred and not to how he thinks that they should have occurred. Fortunately, in this case, the author passes the test with flying colours. He gives a wonderfully rich account of all sorts of facets of the life of the Goan community in East Africa whilst not shying away or ignoring some of the more difficult issues that confronted the community or the life that they led in Africa. He explores a multitude of themes and raises difficult issues and questions of morality in a believable but accessible manner. Issues of hierarchy, race, religion, morality all find themselves worked into the wider themes of family, community, education, economic opportunities and bureaucratic realities all within the wider imperial framework.

I would say that it is a delight to read an imperial story from the perspective of those who are most certainly not the rulers or the privileged. Braz Menezes presents the story of an average family attempting to make the best of the opportunities of the world that they find themselves in. They are not the great and the good. They are very much buffetted by forces beyond their control but equally they find opportunities in the colonial system that would not exist without these empires. They are the kind of people whose story is very often forgotten but whose story was oh so typical for so many people.

The Goan community found an unlikely niche within the British Empire despite being from a Portuguese colony dating back some four centuries and having undergone a completely different imperial experience to most people from the Indian sub-continent. The Portuguese Empire had been around longer than the British one and its colonies stretched back towards Africa and on to Europe via Mozambique, Angola and Brazil amongst other colonies. Many Goans had also embraced Catholicism over these intervening centuries - although as this book makes clear - in a defiantly Goan manner. The combination of Christianity, an industrious work ethic and strong familial and commercial links across the Portuguese Empire meant that Goans were more at ease than most Indians in crossing the Indian Ocean in search of new opportunities whilst still keeping fierce links to the land of their birth and to their distinctive Goan culture. This book clearly explains that cultural diaspora effect. For instance, it explains why Lando's father crosses to Africa en route to Mozambique in 1928 but also why he stops off in British administered Kenya - whose administrative efficiency immediately strikes him favourably compared to the Portuguese one he is familiar with. It explains how the network of Goans in British Kenya helped newcomers to find positions, accommodation and helped them settle in to their new home. It also explains how the British authorities soon found these Goans indispensible in so many levels of middle management from banks to government to the railways to commerce to pretty much every facet of the economy. The sympatico arrangement largely suited both sides whilst still presenting difficulties and issues as the book makes clear.

Although Lando is the focus of this book, it brings in other friends and relatives to build up an ever more complex set of characters and situations which allows the author to bring in more and more snippets of information about the Goan experience. This could be the means of travel from Goa to East Africa, the foods eaten, the educational opportunities for the children, the racial difficulties encountered and the complex stratification of a colonial society with its unwritten but somehow rigid pecking orders that everyone seems to implicitly understand. Luckily, having a child as a protagonist for much of the book, there are plenty of opportunities to explain these finer subtleties to the youngster's enquiring mind as new situations arise and present themselves.

In fact, the structure of the book really does have to be commended. Each of the chapters is short enough to allow a particular focus, character or event to be explained or to unfold within a largely, but not completely, chronological narrative framework. However, there is wonderful, if subtle, signposting and referencing going on throughout these chapters. You are frequently reminded of half forgotten events or characters or have had the ground prepared before new events unfold or bit characters push themselves to the forefront of a particular chapter. This delicate stitching together of the complex web of characters, locations and events really has to be read in its entirety in order to fully appreciate how well it all fits together. The author also has a very clear way of expressing himself and so the complexity of his structure is beautifully hidden and you can read through the book at a good clip whilst only later appreciating just how well integrated the story as a whole has been achieved. It should also be pointed out that there is an undercurrent of humour throughout these pages. Some of the chapters really do have laugh out loud moments for the reader to enjoy. For example, Lando and his friend are not allowed to enter the kitchen where his mother is preparing for Christmas as they are treated "like predators: vultures that circle above a carcass, waiting for the right moment to strike." or at another party where the young Lando sees "friends of our parents, who we assumed were year-round cripples, jump and jitterbug in gay abandon". This infusion of humour adds to the ease of accessibility whilst never detracting from the more serious points raised.

I would hate for someone not to read this book as they thought that it might be too specific an account of just one community in one part of the Empire. Nothing could be further from the truth. Although the focus is on the Goan community in East Africa there are a number of reasons why this book transcends any danger of parochialism. Firstly, and as already mentioned, the Goan diaspora was very widely geographically dispersed and this book certainly goes beyond the confines of East Africa with references and characters connected to Brazil, Angola, the Seychelles, Aden, India and many more places besides. Secondly, the nuanced account of life for this one Goan family has a universality that should appeal to any reader. The themes of childhood, pets, family gatherings, special occasions, marriage, work are not specific to any one community. The characters in this book may be Goan and they are experiencing the world through their own cultural perspective, but anyone should be able to relate to the basic emotions, desires and dreams of the characters portrayed. And nearly anyone can imagine how these themes and their consequent difficulties would be amplified by living away from home in a different environment and culture. Thirdly, the characters themselves are very interesting and generally sympathetic. They are fun and interesting to be with. They delicately impart wider information and knowledge about life in East Africa in a non-lecturing and almost accidental manner. Any reader is learning more in their company than they might realise. Lastly, the book deals with important issues of identity and especially for a migrant culture. For example, at what point does one stop identifying with the culture of one's parents and identify with the culture of the land you grew up in instead? How do you deal with the intermediary of a colonial culture with its own rules and values which are different from both your own culture and the host culture you are growing up in? In essence, this book reveals the subtleties of life in a hierarchical colonial system responsible for allowing people from one part of the world to live and work in another part of the world. Many of today's migrants might find powerful parallels whatever their own cultures and the destinations that they have found themselves in. And even if you are not a migrant, you can certainly empathise with the difficulties and issues that migrants have to contend with and as this book relates and explains.

To tell the truth, I am not generally a fan of historical fiction. Too often I feel that the author has taken too many liberties to dramatise events or bring in some un-required sexual tension or adds some violence or shocking event to make it more exciting for the reader. I often feel that historical fiction is written as a screenplay for a not particularly great Hollywood film. However, this book does not fall into that category at all. I would say that this is a beautifully nuanced account that holds your attention and interest throughout without resorting to cheap tricks. It is just good, old-fashioned story-telling at its best. Its characters, subject matter, authority, organisational structure all come together to reveal the subtleties of life for the Goan community within one corner of the British Empire seen through the prism of one young boy and his wider family's experiences. I am so thankful that this is just the first of a trilogy and that there is more of the story to unfold yet. This may be labelled historical fiction, but I have a feeling that many readers would learn more from this fictional account than many would from a traditional non-fiction history book. I sincerely hope that there are many other authors out there from other communities who can write equally authoritative and convincing stories on behalf of other peoples of whom they know as intimately as Braz Menezes knows of the Goans in East Africa. I would love to similarly read about Pacific Islanders dealing with life in Australia or New Zealand, or Indians in Fiji, or the Cornish in South Africa, or.... the list is endless on the permutations and combinations of migrant groups within the British Empire and every one of these communities has a tale to tell to the rest of the world. Thankfully, the Goan community of East Africa has found one author who has articulated their experiences so thoughtfully and so accessibly. He also provides a blueprint for other historical fiction authors on how to use this format to add to historical knowledge and understanding. 'Beyond the Cape' will start you on a voyage of learning that you may not even have realised you had embarked upon.

|

|

Review of Volume Two: More Matata: Love After the Mau Mau

|

|

Braz Menezes' second volume continues the story of Lando and the Goan community in East Africa after the young man returns from his unhappy time in a boarding school back in Goa. It follows him through the upheavals of the Mau Mau rebellion and towards independence for Kenya in 1963. The book actually connects the reader to even more modern events on the eve of the election of Barack Obama (with his own Kenyan connections) to the presidency of the United States and to the backdrop of Kenyan political upheavals following their own 2007 elections. The author cleverly links these two events to the final days of empire in East Africa and gives some insight into how the seeds for future disruption and discord were sown in the last days of British rule.

It would certainly be best for any reader to have already read the first book before embarking on this one. There is a great deal of continuity in the storyline. Besides, much of the character development had reached an advanced stage by the end of the first book. The author also cleverly reminds the reader of events from the first book, so if there has been a gap between reading the first and the second book, your memory is gently and helpfully jogged for you on a number of occasions.

Lando has to survive an education system in flux during this book as the evolving political climate puts new demands on the British authorities in East Africa. The differing syllabus from the education system back in Goa is also highlighted. The study of Sir Francis Drake rather than Vasco de Gama or subjects like the Hundred Years War help highlight how competing colonial cultures promoted their own heroes and events and as Lando is back in the British Empire, he has to return to learning about British priorities if he is to get ahead in this particular colonial society. Indeed, a new educational opportunity presents itself to Lando in the form of a Technical College opening up. Again there is a good explanation for the underlying trends of modernising education in Kenya in this critical period and how these reforms played out institutionally. It might also be pointed that Britain itself was also revolutionising its own education system, but it is interesting to see how the trends in the mother country played out in the wider Empire and especially at a time when the government was under pressure to highlight the developmental aspects of colonial rule. In Lando's case, he finds the non-Catholic school far more racially diverse than anything he had hitherto been used to in Kenya. However, the differing speeds of modernisation and attitudes are highlighted when he goes to buy his uniform and still has to enter the premises by an 'Asians Only' door on the side of the building. Furthermore, Lando increasingly discovers for himself that attitudes to race may be more complex than he realised when he finds that the teachers hired directly from Britain treat the students far more equitably than any white Kenyan settlers would ever have treated them. The subtle differences in attitudes towards race and identity from a whole variety of communities and individuals are one of the really interesting aspects of this trilogy as a whole. The story reveals that there is both an element of individual choice in attitudes to race whilst still having to work within constraints or expectations from a surrounding culture or group of people. So, soldiers, settlers, British, Goans, Africans, tribes, rich, poor... might all have an umbrella starting point to racial attitudes, but each individual can select for themselves whether to embrace those group norms or forge ideas and concepts of their own. These ideas on race also develop and change over time and through experience - this is certainly evident from one generation to the next, but it also might change and develop within a single person's life time. None of this is stated outright in the book, but careful reading allows you to follow a multiplicity of attitudes towards race in a part of the Empire that had very much been defined by racial differences and found itself catapulted towards having to address these issues sooner than had been anticipated.

The first manifestation at having to confront issues of race, tribal identity and raw power politics was in the form of the Mau Mau rebellion in the 1950s. Of course, this coincides very much with Lando's formative years in the 1950s and his years of education. Once again, the book does a good job at explaining how the realities of this emergency seeped into the everyday lives of all concerned - even for the liberal British teachers who found themselves uncomfortably carrying around pistols to defend themselves from unknown Africans - the very people some of them presumably were keen to come to Kenya to help in the first place. The difficulties of drawing simple lines to cast various groups into categories of oppressor or troublemaker afflicted all sides in the Mau Mau rebellion and many innocent people from all sorts of communities found themselves victims of powerful forces beyond anyone's control for much of the decade. The conflicting views of Goans themselves towards independence and the Mau Mau form a powerful thread through this second book. There are those who sympathise with the aspirations of Africans but appreciate that their own community had been some of the biggest beneficiaries of European rule with their relatively privileged positions in government and leading industries and businesses at least vis a vis the Africans. Idealism conflicts with realism for all too many and the steady stream of Goans heading for the exit through the 1950s and early 1960s help illustrate that the fears of many overcame their hopes. Although we see that Lando himself, despite being buffetted by the 'Winds of Change', still remains optimistic that Asians can find a place in the new Kenya after 'Uhuru' in 1963. Indeed, he himself wins a coveted prize to design some of the Independence Day decorations and enthusiastically takes part in the celebrations as the infectious enthusiasm obscures some of the nagging fears in the back of people's minds. Although when he attempts to gain a passport, he notices the low issue number for an Asian applicant such as himself and realises that the majority of Goans are seeking British or Indian passports rather than Kenyan ones and voting with their feet before various bureaucratic barriers fall in their wake. Idealism for many Goans might have serious consequences although that is a subject for the third book perhaps.

The book also introduces Lando to the difficulties and realities of love with the enigmatic Saboti being the object of his affections. The love story is also an opportunity to examine the difficulties and issues of mixed race births and inter-racial relationships in what can make for uncomfortable but important reading. Of course, even the Goan community's own, often close-minded, attitudes towards mixed relationships enters the fray and the way that even though they are predominantly Catholic in culture, many of their attitudes towards race and caste at times appear not to veer that far from Hindu Indian attitudes or at least might be characterised as deeply conservative in origin. Again, it would be all to easy for an author to brush over difficult and embarrassing issues and tell a hagiographic story of progress and virtue. Hats off to Braz Menezes for not shying away from difficult issues and addressing them in a highly believable and informative manner.

Once again, the author manages to continue to weave the compelling story of the Goan community through the very last years of imperial British rule and takes Lando's story through to the new dawn of an independent Kenya. I look forward to reading how Lando's dreams, aspirations, hopes and fears all unfold in the final part of the Matata Trilogy in a post-colonial world - although the Trilogy's title of 'Matata' may give an important clue to how Lando's story plays itself out.

|

|

Review of Volume Three: Among the Jacaranda: Buds of Matata in Kenya

|

|

Braz Menezes continues Lando's saga into the post-Colonial age for East Africa. This is clearly a confused period of apprehension, optimism, fear and hope as the Goan Community embrace the opportunities of Kenyan Independence but do so alongside darker concerns that they may not find themselves as welcomed in this African country as they were during the period of Imperial rule. Had they made themselves indispensible to Kenya? Or, were these 'Asians' seen as a painful legacy of Colonial control by the Africans so keen to embrace the freedoms promised by the departure of the British. Lando's story illustrates a confused path whose ultimate destination was not clear to the many Goans who trod a similar route through history just as it not clear to Lando!

The story picks up in newly independent Kenya. Lando, still flush from his Design Awards from the Uhuru celebrations embraces a future in architecture in the service of the new Kenya. As such, he is offered a place to study in Britain with an urban planning scholarship from the Commonwealth. This in itself shows that the ties to the old imperial power were not completely severed. Ties of language, education and the long historic connection still made Britain a natural base and place of study for the emerging Civil Servant and professional classes that Kenya would sorely need as British personnel departed. It also illustrated that some kind of continuity for the Asian community of Kenya was anticipated and expected, even officially.

Before Lando leaves for his studies, he is reunited with 'Stephen' whose father had been detained during the 'Emergency'. He had been a faithful servant family caught up in the ethnic tensions and the fight for Independence in the 1950s and early 1960s. Stephen's case shows an interesting concept of noblesse oblige felt by many Goans to their African servants even though the concept of being able to have servants in the first place might seem alien to those brought up in the modern world. The author drops subtle hints at the pangs of guilt and obligation felt to any member of the household and how loyalty and friendship could be fostered amongst those who held a seemingly unequal professional relationship. It is just one more of those interesting human connections that these books help illustrate and show that life was not always simple and straightforward and did not always fit into neat boxes like 'modern' and 'traditional'.

Lando is also aware of the tensions and mixed feelings of Asians as a whole in this new country. Many have decided to leave but the practicalities of doing so are revealed by Lando himself being caught up in the complications of currency restrictions. As someone who is going to be a poor student on a Scholarship it is mere inconvenience, but for families selling their life's possessions, property and trying to get the wherewithal to start a new life in a new part of the World it is a deadly earnest consideration requiring a great deal of time and effort to negotiate and navigate. The newly independent Kenya with its own new currency did not want to see a flight of capital alongside the flight of expertise... This made the decision to stay or go even more difficult still for many.

Lando's journey to Britain also reveals that the Mother Country itself had diverged greatly from its own imperial past. Colonial peoples used to Europeans living a privileged life were often surprised to find many Britons at home being far more tolerant, interested and relatable than those they had encountered back in the colonies. Of course, this was still at odds with the era of Enoch Powell and growing resistance to immigration much of it inspired by post-colonial obligations to colonial peoples being honoured by the authorities. This dichotomy is explored in an interesting conversation with an elderly lady on the train from London to Liverpool. There is also the culture shock of Lando seeing Europeans doing the mundane jobs of cleaning the streets, collecting rubbish, working long hours in menial roles etc... seeing white people do jobs that they would never have done in the colonies would indeed have been something of a revelation.

Lando's time studying Urban Planning in Britain illustrates the cosmopolitan lifestyle alongside that of being something of an ex-pat himself. His scholarship opens doors and puts him in touch with broad minded fellow students and eventually a budding romance with a fellow student. Eleanor very much becomes the focus of the remainder of the book. She also is a European who is very different from the colonial mould expected of whites. Lando's friends and family had teased and warned him that many Goans go overseas and find a woman but assumed that falling in love would not happen to him in such a foreign culture. However, love strikes where love strikes. The book then takes a tour through Europe as the lovestruck young couple explore the world in one another's company... the themes of growing tensions in Kenya and the perspective of seeing Europe through the prism of an Urban Planning student of Asian/African descent follow them on their adventures. There are many intriguing conversations where Lando finds himself often nostalgic for the freedoms and opportunities of the old colonial Kenya but also aware of the harsher realities of aspects of colonial rule. Lando is both broadening his own horizons and those of people he meets along his travels through Europe and back in Liverpool. One such insight is gained from seeing a sectarian Orange Parade through Liverpool. The explanation that Liverpool's influx of Irish workers in the 19th Century was due to agricultural workers being forced to find work in the new urban centres in the aftermath of the Great Famine would have painful parallels in Kenya. Kenya would likewise suddenly see a massive influx of agricultural workers to her cities which would literally explode in population terms. Problems like this would soon overwhelm budding urban planners in post-colonial societies across Africa and beyond as populations sought a better life for themselves than an agrarian existence could provide. Unfortunately, people were as likely to find a new kind of urban poverty as any kind of consumer success story. It took the Irish in places like Liverpool over a century to climb the economic ladder to normality... would Kenyans have such patience when they were promised so much with Independence? In many ways, Lando's idealism kicks in as he explains to Eleanor his desire to help build housing for Kenya's poorest Africans but to what extend did Africans want Asians building houses for them... the mixed messages coming from East Africa were not reassuring.

Eventually the budding love does result in a marriage proposal. The very idea of a mixed marriage could be as much of a culture shock to Goans as it could be to Europeans. Undoubtedly there was great racial turmoil in the 1960s and reservations from parents would more likely have been out of care and compassion rather than anything more sinister. Still Lando's desire to return to Kenya and help the country of his birth are in no way undermined by his new bride whose broad-mindedness and adventurous spirit is thrilled by the idea. Still the realities of building a new life in Africa for a young family would have been tough at the best of times but in a period of racial tension, not so much directed at the Europeans who were transitioning rapidly to the new reality but towards Asians, were palpable. Many Africans were still suspicious of this class of people that they regarded as something of an unwanted legacy of Empire. It did not help that salaries were capped for locally hired people. Bizarrely this policy helped keep communities apart. Although the idea of European, Asian and African areas had officially been swept aside, the realities of pay differentials made it very difficult for anyone not on an overseas contract to live in a European area and of course Lando wanted to try and make his new bride comfortable but on a lowly Kenyan salary that would be a difficult task to fulfil.

Perhaps the most impressive part of the book is the view of post-colonial Kenya given. In a wonderfully nuanced description it explains the new vitality, brightness and bustle of this young country. With no colonial restrictions on imports and industries, there is a veritable explosion in the variety of cars and consumer goods available. These are accompanied by garish advertising hoping to tempt Kenyans with these new goods. You get the feeling of a period of hope for the future almost like a canvas of sepia tones being swept aside by one of bright, primary colours. There follows a fascinating description of the newly evolving melting pot making up the new Kenya. For the Europeans there were the old fashioned Wazungu who might have been descended from the old settler class who had already arrived and still felt an air of superiority and authority. Then there were the Wageni who were the newly arriving Europeans often taking up new roles and opportunities be it missionaries of new branches of Christianity or aid workers undertaking new development projects or tourists arriving on the new jets flying in and out of Kenya. These were as likely to be North American as European but either way they tended not to have the old hang ups or expectations of older colonial attitudes. These Wageni were far more multicultural and cosmopolitan than the older Wazungu community but also far more transient and possibly less invested in the long term future of Kenya as a whole. The Asians were lumped together as Wahindi which must have infuriated Goans with their own Catholic heritage - the inability for outsiders to differentiate the various influxes of Asian migrants perhaps hinting at their vulnerability. Then there is an expansive explanation of the various African groups including the interesting colonial legacy of Sudanese who had fought for the British in the Kings African Rifles and were rewarded with land in Kenya. It was not just Asians and Europeans who were moved around the Empire, Africans could be too! And of course refugees also appeared from neighbouring and nearby countries as Africa was very much being convulsed by the decolonisation process on a much wider scale than just the British leaving! All these insights showed the complexities and realities for a new country tiptoeing towards an uncertain future. Eleanor's people spotting gives a fascinating insight to what was a remarkably cosmopolitan country. There is a lovely phrase given about all the turmoil and upheaval reported on the radio and in the papers.... the 'white noise of a colonial system being expunged'... The increase in feverish activity, the rise in crime, the migration of peoples to the cities, the straining of old government services and uncertainty for the future vie with the new hope and fresh influx of peoples for whom colonialism was either unknown to them or a rapidly fading memory.

The practicalities of the growing exodus of Goans impinge upon Lando's life as their planned reception becomes something of a race to organise before too many family friends disappear overseas never to return. There is much debate on the pros and cons of leaving. Not all Goans who migrated were finding the grass greener on the other side and stories of difficulties in the West and a very different lifestyle were trickling back causing some to hesitate. However, the trickle seemed to continue relentlessly. Events planned for Christmas and New Year become difficult to organise as the Goan Community hollows itself out. Previously sold out venues struggle to make the events viable. It should be said though that the exodus also produced opportunities for those who remained as jobs might become available as suitable qualified replacements were in such short supply. Africanisation may have been a goal for the newly independent nation, but even Africans needed a minimum amount of qualifications and experience to take over some of the roles. We understand that Lando and Eleanor are very much swimming against the tide, but they find that there were opportunities even in these uncertain times. Colonialism was giving way to globalism... new corporations were arriving just as older ones were departing. Lando takes the plunge in buying a new property for his new family as it expands in size. As he sits amongst his Jacaranda trees in his new domain it appears that there might be a silver lining to his future and that he may well be able to design and build new projects for the country of his birth. However just as there appears to be light at the end of the tunnel an unexpected disaster befalls Lando... will it force him to reevaluate his life choices? will it lead to changes? How will his family cope? We will have to wait for the next installment to find out!

|

|

Review of Soul Searching in the Seychelles

|

|

Now it may seem odd to have a fourth book in a trilogy, but Soul Searching in the Seychelles is actually something of a transition book which keeps the story of Lando and his family alive and takes it deep into the post-independence travails of Colonial East Africa. Indeed, this book introduces us to the decolonisation process and issues of yet another British colony, that of the Seychelles, which did not achieve its independence until 1976.

As in the previous three books, the author weaves together fact with his semi-fictional characters journeying through this era. He explains that the Seychelles really were a colonial construct from start to finish - if not always a British one. Nobody had lived on the islands before European mariners were to stumble across them as they sought new trading routes to and from the Spice Islands of the East. The Portuguese spotted them first, but it was the French who claimed and settled the archipelago. Indeed the name was given in the Eighteenth Century in honour of Viscount Jean Moreau de Séchelles the finance minister of Louis XV. Captains and explorers often bestowed names of newly claimed lands on well connected courtiers who they hoped might feel better disposed to providing them with further resources and preferment. Anglicised to the Seychelles, the islands of the Indian Ocean would become pawns in the maritime battle for supremacy of the seas between Britain and France. Eventually, it was the British who were triumphant in the light of their victories at Trafalgar and Waterloo. The well placed islands would complement their other gains at the Cape Colony and the growing importance of India to the British Empire.

The French provided the islands with slaves to work on their plantations. This provided the foundation for what would later become the Seychellois creole population. The British had abolished the Slave Trade in 1807 but when they took over they continued to utilise slave labour until they abolished it fully in 1834. Ironically, the islands would later be used by the Royal Navy's anti-slaving patrols dealing with the less well known but equally extensive Indian Ocean slave trade triangle between East Africa, the Middle East and India. This was largely under the control of the Sultan of Muscat and Oman and had allowed Zanzibar in particular to become a rich and powerful slaving entrepot. In its quest to stamp out all slavery, the Royal Navy would release some of the slaves that they had captured from the Arab and Zanzibari traders upon the Seychelles providing yet more genetic mix to the islands' population. This was further enhanced when British steamships run by William Mackinnon and William Mackenzie began to ply the waters regularly. What became the British India Steam Navigation Company in 1862 connected hundreds of ports from Europe to Asia and so many in between. This was formalised even further after the British took control of parts of East Africa and yet more products and people flowed to and from the Indian sub-continent often stopping off at the idyllic Seychelles en route. And not a few of those passengers decided to stay and seek their fortunes on the archipelago itself.

Indeed this is kind of the story of the book, if set a little later in the dying days of colonial rule. As a trained architect who is trying to make his way in post-independence Kenya an old friend and colleague offers Lando and his family an opportunity to take over a relatively thriving architectural firm in the Seychelles - or at least as thriving as it can be when all the materials have to be imported and with such a small work force to draw upon. The English architect, Graham McCullough, invites them to the islands and arranges for them to stay at the prestigious Mahé Beach Hotel whose construction and design his firm had overseen. Like many people who have opportunities presented to them, they weigh up the advantages and disadvantages and consider issues like schooling, qualifications, friends or should they wait for other opportunities in Britain or Canada? Notwithstanding the beguilingly beautiful environment they find themselves in, Eleanor sides with the devil that they know and that they should remain in Kenya, at least until Lando reveals that he was told by the Head of the Civil Service that he was to be deported. This was due to his role in thwarting a Minister’s attempt to corruptly interfere in a major housing project. Corruption is the cancer that is slowly throttling the ambitions and opportunities of too many post-colonial African nations.

The Seychelles opportunity returns to the table as a consequence. What unfolds in the archipelago is sadly a parable that took place in too many post-independence countries. There is an initial wave of enthusiasm and hope at the birth of a new nation. The Mahé Beach Hotel hosts the dignitaries of the independence celebrations no less and it soon adds a Presidential Suite for the head of the new country's government to entertain diplomats and businessmen from overseas. The future seems bright with post-Independence opportunities for the tourist trade erupting with the new cruise ships and jet planes that can cut the time of travel to allow for short vacations to burgeon. Yet within a year a coup d'etat - literally as Lando is dotting his 'i's and crossing his 't's - throws a spanner in the works. As far as Lando is concerned his entire venture is pulled from under his feet as the Seychelles diverts from its Capitalist directions towards the Socialist model through the barrel of a gun. The local population will gain in terms of health and education but the economy will become sluggish and opportunities decline. The fate of the Mahé Beach Hotel perfectly encapsulates this decline as the book explains. Worse even than the physical deterioration is the fact that opposition campaigners will be mistreated after arbitrary arrests and some will disappear altogether. Within a matter of hours the Seychelles moves from the idyllic to the concerning column. Lando's adventures will not take him to the Seychelles after all.

It should be said that this is a notably shorter book than the other three. But as I mentioned earlier the author is using this book as something of a prequel for his next book, the Money Eaters of Tsavo which will follow that cancer of corruption in East Africa much further down its rabbit hole of misery. In the meantime, this book also provides lots of further information on the people and places mentioned in the book - the architects, the politicians, the places, etc... It also introduces some of the Seychellois diaspora who sometimes follow a similarly itinerant existence to Lando's Goan community. I think this book would make a perfect companion to anyone travelling to the Seychelles as it examines the opportunities and threats of independence and looks at some of the consequences of those decisions. It is not saccharine sweet as many tourist books can be but it also is not too dystopian and negative either. It is charitable in places and offers an honest appraisal. Anyone with a connection to the Seychelles will see that positives and negatives exist as much in paradise as anywhere else.

|

|

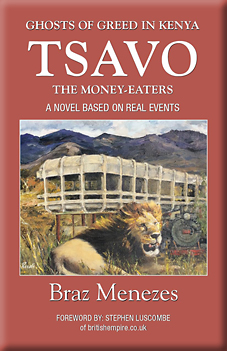

Review of Tsavo: The Money Eaters

|

|

The subtitle of the book as "The Ghosts of Greed in Kenya" hint ominously at the overwhelming narrative that comes out of this fifth and final book of the Matata series. This has been a remarkable set of books that charts the rise and fall of a Goan dynasty in East Africa as they switched from one Empire to another and then found themselves in an independent African nation all within the space of half a century or so. But half a century was enough time to put down roots, make friends, have children, be educated, have careers, say goodbye to loved ones and live normal lives in an extraordinary setting. Basically it is the culmination of the previous four books and expands upon the post-colonial realities for a mixed race Asian family in an African nation whose people did not always wish to be reminded of their colonial heritage and even more than that wished to replicate the perceived lifestyles and riches of their former colonial masters. If there is an over-arching theme of this book it is the one encapsulated by Lando towards the end of the book when he sadly considers that "The moral decay reflected in metastasizing corruption appears unstoppable." This is a book that charts the cancerous effect of unbridled corruption as it seeps through the entire body-politik and each and every aspect of the economic life of the country is damaged by its effects. Each individual case of corruption might well be justified to himself by the perpetrator but the cumulative drip drip effect makes economic life all but impossible and even more so for those who strive to remain honest and honourable in a sea of iniquity and unfairness. This is the story of how the milk of independence went sour in the late 1960s and early 1970s and how tiring it is to battle against corruption in every part of life - day in and day out.

The book starts off with the tragedy of the death of the matriarch of the family at the tragically young age of 50 in 1968. The family was already dispersing but with the loss of the mother, Lando's father was in despair with "No sparkle and no depth in his eyes" but with no wish to leave the country where his wife was buried and where he had dedicated so much of his life. The father would provide one of the few strands of the family rope still attached to East Africa as other siblings sought opportunities elsewhere in the world. Another strand would be provided by their African family friend of Stephen who the previous books already explained had become something of an obligation to Lando - although not always the easiest to point in the right direction. Stephen provides a link to the African side of post-colonial hopes, fears and difficulties. We see Stephen's trajectory rise and fall like a roller coaster as continual optimism battles with reality and the limitations of education and opportunities. He illustrates that tribal and political loyalties presented their own complications for the African population. There was no united African experience in a tribal country like Kenya. The corrosive effects of corruption hurts nobody more than the poor people at the bottom of society who are often the foremost victims of public works or governmental schemes designed to help them but which often provided the perfect opportunity for unscrupulous politicians and contractors to rob them twice - once through taxes stolen and again through failing to provide the promised facilities or provide them at a pitifully poor standard. Maybe if they hadn't had their expectations raised so much by the politicians they wouldn't have been quite so disappointed at the outcomes. However, the new 'democratic system' required ambitious promises and when the politicians failed to deliver on them, their only recourse was the creation of a one party state based on tribal loyalty and whose critics could be savagely beaten, imprisoned or as this book reveals even murdered.

There is a constant tension between Lando and Eleanor as they discuss and debate the merits of staying in the wonderful climate and colourful society of Kenya with its growing professional opportunities for the all too few remaining skilled architects and planners like Lando vis-a-vis the daily realities of corruption, crime and racial tension. Machete gangs break in to houses, police are as likely to rob you as help you at their road blocks and the sheer inefficiency of corrupt officials makes even the simplest of jobs onerous in the extreme as various officials slow things to a crawl to maximise their leverage to exact bribes. Legal documents like passports and contracts lose their value in a capricious system where it is more important to have the right political or official contacts than it is to have the correct paperwork in order. The Mercedes Benz appears to be the real symbol of this increasingly kleptocratic state. Time and again Lando comments on seeing the arrival of Mercedes Benz cars with a sinking sensation as he realises that it means that the "WaBENZi" have become involved. You know you are living in a corrupt state when the local population creates vocabulary to describe their less than honest officials as corruption has become so ubiquitous. Another word I reluctantly learnt from this book was the 'chini-chini business' basically a business created specifically for the purposes of corruption. And the tell tale sign that you were dealing with a a chini-chini was the arrival of the Wabenzi car with its supposedly prestigious passengers to 'negotiate'.

The author explains how the Asian exodus also had its effect on domestic British politics with a tightening of the immigration laws there in 1968 in reaction to the rise of politicians like Enoch Powell. Soon the right to settle in Britain was to be made more difficult which in itself caused a fresh stampede of Asians from East Africa to try and get their paperwork and visas completed before that door was slammed shut to them. To make matters worse for the Kenyan economy, the Kenyan government began clamping down on visas for Asians who did already have British passports in an attempt to force Asians to decide to take up Kenyan citizenship or leave for good. The Kenyan authorities didn't want to enable Asians to have their cake and eat it; to have a British passport but continue to live and work in East Africa beyond their political and therefore economic reach. So yet more Asians who had previously hesitated leaving began the process of selling their properties and goods and making for the airport in numbers so great the airlines had to put on extra flights to deal with the demand. Not that getting to the airport would see an end to the corruption, indeed the officials there seemed to create a fine art in fleecing departing Asians with spurious claims of invalid documentation or visas that could be 'rectified' for a fee - in cash of course.

The contrast for a friend of Lando's whose wife had a serious car crash just before emigrating to Britain could not have been more stark. They were nothing but effusive at the help from the British authorities and the medical care received through the National Health Service as the emigres had done everything legally and by the book and so were entitled to the free medical care but even more than that the relief at not having to operate in a new land riddled with corruption, where you could believe that officials and professionals would do their best because it was their job to do the best. We have to remind ourselves from this series of books that it was the relative lack of corruption in the British Empire that so appealed to many Goans when they first set out looking for new opportunities. There is no accident that so many Goans would seek to find new lives in Britain or other Commonwealth nations like Canada, Australia and New Zealand all renowned for being fair and just societies and all based on the British legal system.

Despite all the corruption in East Africa we see that Lando is able to carve out a professional niche as his pool of rivals gets ever smaller as they fly off to less hostile countries. He is able to win contracts for some tourist lodges on the edge of Nairobi; works with Shell on various forecourts and premises; and eventually lands a large contract to provide social housing for some of the poorest Kenyans in the growing urban slums. He even manages to land a coveted contract with a United Nations agency who are frustrated at having to deal with corrupt local officials and turn to him in something of desperation. This is no simple upward trajectory of success. The murder of Tom Mboya the Minister for Economic Planning and Development hits particularly hard in 1969 and causes a number of projects to be cancelled or suspended as international investors in particular take fright at the internecine rivalries unfolding in Kenyan politics. The conclusion is somewhat counterintuitive as Asian businesses are looted for an African killing of an African. It then sees Kenyatta double down on the creation of his one party state ostensibly to restore law and order, despite it being his own supporters and system that is responsible for the murders and looting in the first place.

But soon Kenya seems like a paragon of peace and tranquility in comparison to the dark events unfolding in neighbouring Uganda where a little known soldier 'Idi Amin' is thrust into world wide public consciousness. As the Ugandan kleptocratic state flounders in its even deeper mire of corruption, he shamelessly turns on the Asians to provide a convenient scape goat for his country's failings. Originally it is those same British passport holding Asians as in Kenya who receive his full ire. They are given 90 days to wind up their lives and get out. Many of them leave with little more than the clothes on their back and what little they can carry. Technically only 30,000 are forced to leave but 80,000 appreciate what will happen next and rush for the exit themselves. Shock waves spread throughout the wider Asian communities in East Africa and yet another bout of soul-searching is done by those trying to give the countries of their birth the benefit of the doubt. The Uganda robbing of Asians emboldens officials in neighbouring countries as the Asians are all too conveniently identified as the reason for African poverty and economic failure. The so-called 'shuttlecocks' are Asians who find that their travel documents and official documentation are not as valuable as they had assumed and they are knocked from High Commission to Embassy to airport to wherever in the desperate search for security and safety.

And as all this political and economic uncertainty unfolds we see that Lando's own architectural achievements go from strength to strength as they win coveted contracts and are one of the ever decreasing firms that actually at least attempts to deliver what they are contracted to do so. However, even they struggle as they discover that partners and contractors of their own are frustrated by unpaid bills, onerous paperwork hiding attempts to extort money from them and unkept promises by politicians. The authorities not only offer little protection, they are often the perpetrators of the corruption or abuse of power. Two tourist safari lodge contracts of Lando's come to embody difficulties of operating in such a hostile economic environment. One of them actually does get completed but only with the greatest difficulty and with untold problems with contractors and payments and substandard materials. It does not help that the promised infrastructure to the lodge is not provided again as government funds allocated to the roads and bridges mysteriously vanishes into thin air. The Tsavo lodge designed to cash in on the fame of John Patterson and the Lions of Tsavo is soon revealed to be nothing but a scam from start to finish (a chini-chini business mentioned above), although one designed to rob not just the government but also the various contractors, landowners, architects and those foolish enough to believe that creating jobs and opportunities for Kenyans to exploit and capitalise on the tourist industry would be a good thing for Kenya. It is this heart-breaking episode that provides the title to the book and encapsulates all that has gone wrong with post-colonial Kenya. However it is not the straw that breaks the camel's back for Lando and Eleanor, although it may be the penultimate one!

The last family strand of that rope keeping Lando in Kenya is undone when his father passes away. His father had invested too much of his hopes and dreams and life into Kenya to leave it at such a late stage in his life. Eventually his ever diminishing band of friends and family sees his world shrink and sadly his mind seems to contract with that declining pool of support. With his death there is one less excuse to remain in Kenya. And when there is yet another high profile political murder of 'JM' - Josiah Mwangi Kariuki - a potential rival to Kenyatta - Lando's and Eleanor's resolve to continue finally breaks. They have realised for a long time they are living in an increasingly authoritarian and brutal one party state but this is one upheaval too many for a family that kept giving itself excuses to stay. The corruption, political uncertainty and exodus of almost their entire family and friend support network finally pushes them over the edge to commit to exile from Kenya. Lando does have the luxury of having formed a strong commercial relationship that gives him time whilst still working on paying projects so they have time to gather themselves, sell their goods and property and prepare for a new life elsewhere. But the African dream is over. Half a century of 'matata' which can be translated as 'trouble' or even better yet as 'entanglement' in East Africa finally saw the family cut itself free and start a new adventure elsewhere!

Lando's family are some of the last bits of flotsam and jetsam of Britain's East African Empire. Intriguingly they wash up in another part of Britain's old Empire, that of Canada. In half a century his family moved from the Indian sub-continent to East Africa to Canada and with wider family still scattered in Britain and throughout the Commonwealth - if that is not a remarkable imperial story in itself then I do not know what is! These five volumes may concentrate on one particular family but in reality it tells the story of the rise and fall of nothing less than an entire colony and the subsequent birth pains of a new country. It illustrates how the British Empire was responsible for people moving in quite unexpected and unanticipated ways and how it helped form and shape the world we live in today - although often not in ways that anyone might have predicted.

|

|

|

|

| Author

|

|

Braz Menezes

|

| Published

|

|

2015

|

| Pages

|

|

286

|

| Publisher

|

|

CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform

|

| ISBN

|

|

1519724292

|

| Availability

|

|

Abebooks

|

|

|

| Author

|

|

Braz Menezes

|

| Published

|

|

2012

|

| Pages

|

|

314

|

| ISBN

|

|

1480086339

|

| Availability

|

|

Abebooks

|

|

|

| Author

|

|

Braz Menezes

|

| Published

|

|

2018

|

| Pages

|

|

266

|

| ISBN

|

|

1724274848

|

| Availability

|

|

Abebooks

|

|

|

| Author

|

|

Braz Menezes

|

| Published

|

|

2018

|

| Pages

|

|

128

|

| ISBN

|

|

1777438616

|

| Availability

|

|

Abebooks

|

|

|

| Author

|

|

Braz Menezes

|

| Published

|

|

2018

|

| Publisher

|

|

Matata Books Toronto

|

| Pages

|

|

263

|

| ISBN

|

|

9780987796394

|

| Availability

|

|

Abebooks

|

|

|