|

|

|

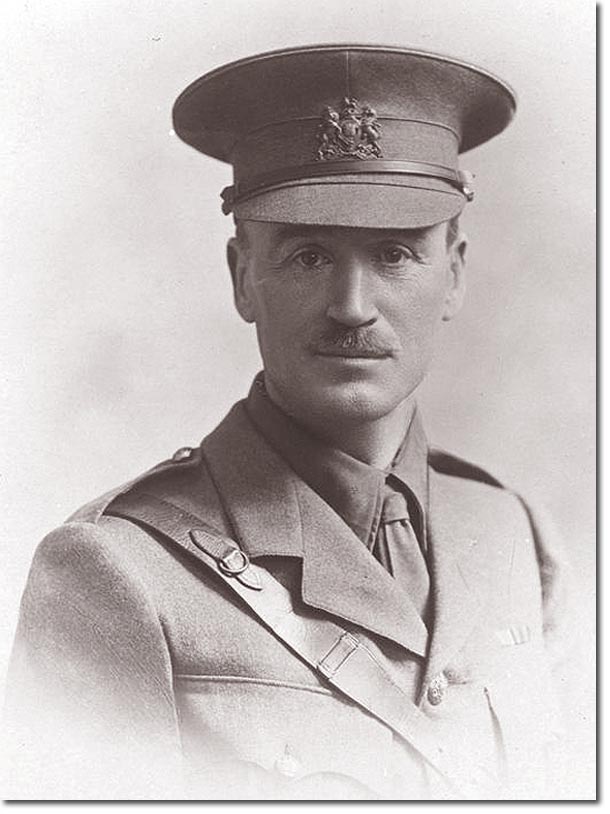

| Colonel John Henry Patterson was an Irish soldier and engineer born on 10th Nov 1867 in Forgney, Co Westmeath to a protestant father and Catholic mother. He joined up at the age of 17 and rose quickly through the ranks. He was assigned to Kenya by the British Government in 1898 to supervise the construction of a bridge over the Tsavo river for a massive railroad project. Unfortunately, railroad workers were constantly being slaughtered by the most notorious man-eating lions in recorded history. Two maneless but huge lions, working together, were estimated to have killed and eaten well over a hundred people working on the railroad.

Night after night, Patterson sat in a tree, hoping to shoot the lions when they came to the bait that he set for them. But the lions demonstrated almost supernatural abilities, constantly breaking through thorn fences to take victims from elsewhere in the camp, and seemingly immune to the bullets that were fired at them. Patterson was faced with the task of not only killing the lions, but also surviving the wrath of hundreds of workers, who were convinced that the lions were demons that were inflicting divine punishment for the railroad. At one point, Patterson was attacked by a group of over a hundred workers who had plotted to lynch him. Patterson punched out the first two people to approach him, and talked down the rest! After many months, Patterson eventually shot both lions. He himself was nearly killed in the process on several occasions, such as when one lion that he had shot several times suddenly leaped up to attack him as he approached its body. He published a blood-curling account of the episode in The Man-Eaters of Tsavo, which became a best-seller, and earned him a close relationship with US President Roosevelt. When World War One broke out, however, Patterson traveled to Egypt and took on a most unusual task: forming and leading a unit of Jewish soldiers, comprised of Jews who had been exiled from Palestine by the Turks. As a child, Patterson had been mesmerized by stories from the Bible. He viewed this task as being of tremendous, historic significance. The unit, called the Zion Mule Corps, was tasked with providing supplies to soldiers in the trenches in Gallipoli. Patterson persuaded the reluctant War Office to provide kosher food, as well as matzah for Passover (and presumably special Pesach mess-tins), and he himself learned Hebrew and Yiddish in order to be able to communicate with his troops. The newly-trained Jewish soldiers served valiantly, but the campaign against the Turks in Gallipoli was ultimately unsuccessful, and the Zion Mule Corps was eventually disbanded. In 1916 Patterson joined forces with Vladimir Jabotinsky to create a full-fledged Jewish Legion in the British Army, who would fight to liberate Palestine from the control of the Ottoman Empire and enable the Jewish People to create a home there. The first unit to be raised, in August 1917, was the 38th Battalion of the Royal Fusiliers, of which Patterson was CO. Four more battalions followed and the Jewish Legion numbered 5,000. They trained largely at Crownhill Fort in Plymouth before being sent to the Middle East to fight. He wrote the following about Raising and Training the Jewish Legion in Plymouth and of their transit to the Middle East. It should be noted that Crownhill Fort continued to accept Jewish Legion trainees even after Paterson had set off for the fighting in the Middle East: "I was delighted when, at last, I got away from organization duty at the War Office, with all its worries and vicissitudes, and commenced the real active work of training a fighting Battalion of Jews. Plymouth was the spot chosen as our training centre, and at the Crown Hill Barracks, near this famous and beautiful harbour, we commenced our military career. A recruiting Depôt was at the same time established in London at 22, Chenies Street, where a Staff was installed under the command of Major Knowles, an excellent officer, who had previously served under me in the South African War, and who was an ardent supporter of Zionist ideals. Recruits were received here, and fitted out with uniforms before being sent on to Plymouth. The comfort of the men while at the Depôt was ably attended to by various Committees of ladies and gentlemen, whose names will be found in the Appendix. They were fortunately in a position to give much needed financial aid to various dependents from the moment the Committees began work, for public-spirited and liberal Jews were found who gave to the good cause with both hands. Among these was Mr. Leopold Frank, who gave the princely donation of £1,000. Mr. Lionel D. Walford especially was untiring in his efforts for the welfare and happiness of every recruit who came to the Depôt, and so won the hearts of all by the personal service that he gave, day in and day out, that he was universally and affectionately known to the Judæans as "Daddy." As a nucleus for the Jewish Battalion I arranged for the transfer of a platoon of my old Zion Mule Corps men from the 20th Battalion of the London Regiment, where they were then serving under the command of Colonel A. Pownall. My best thanks are due to this officer for the help he gave me in effecting the transfer of my old veterans. These warlike sons of Israel, not content with the laurels they had already won in Gallipoli, sought for fresh adventure in other fields, and so volunteered for service in France. On the way their ship was torpedoed and sunk by an Austrian submarine, but fortunately not a Zion man was drowned; all managed to cling on to spars and other wreckage and floated safely to a Grecian isle from which they were rescued. They eventually reached England in safety, but all their personal belongings were lost. Men soon began to arrive at Plymouth in batches of twenties and thirties, from all over the Kingdom. Many trades and professions were represented, but the vast majority were either tailors or in some way connected with the tailoring trade. I made it a practice to see every recruit as soon as he joined and find out something about his family and affairs. I also gave every man some advice as to how he was to conduct himself as a good soldier and a good Jew. The famous sculptor, Jacob Epstein, was one of my most promising recruits, and after he had served for some months in the ranks I recommended him for a commission. When the 38th Battalion left Plymouth for Palestine, Epstein remained behind with the second Jewish Battalion then formed, but owing to some bungling the commission was never granted. The difficulties of my command were not few. On broad religious grounds Judaism is not compatible with a soldier's life—and I may say I had many strict Jews in the Battalion; then the men were aliens, utterly unaccustomed to Army life, and with an inherent hatred of it, owing to the harsh military treatment to which the Jew in Russia was subjected; some of them did not speak English, and practically all of them hated serving any cause which might in the end help Russia; they knew also that there was a strong body of Jewish opinion in England which was hostile to the idea of a Jewish unit. To make matters worse, the recruits came from sedentary occupations. They had never been accustomed to an out-door, open-air life, and naturally dreaded, and really felt, the strain of the hard military training which they had to undergo in those cold winter days in Plymouth. It can be imagined, therefore, that I had no easy task before me in moulding these sons of Israel, and inspiring them with that martial ardour and esprit de corps which is so necessary, if men are to be of any use on the field of battle. I impressed upon them that strict discipline, and hard training, was not merely for my amusement or benefit, but was entirely in their own interests, so that when the day of battle came they would be fitter men and better fighters than their enemies, and with these two points in their favour the chances were that instead of getting killed, they would kill their opponents and emerge from the battle triumphant. The men soon grasped the idea, and took to soldiering and all that it means with a hearty goodwill. I am happy to say that all difficulties were surmounted, and, at the close of the campaign, the Battalion presented as fine and steady an appearance on Parade as any Battalion in the E.E.F. Luckily for me, I had an able and enthusiastic staff to assist me in my endeavours. I cannot sufficiently praise the great service rendered to the Battalion, during its infant stages, by Captain Redcliffe Salaman, R.A.M.C., who was our medical officer. His knowledge of the men and of Jewish matters generally was invaluable to me. My Adjutant, Captain Neill, had already had two years' experience in a similar position with a battalion of the Rifle Brigade. I found him to be able and diplomatic—the latter an essential quality in the handling of Jewish soldiers. In my Second in Command, Major MacDermot, I had an officer of wide experience and high principles, who had served under my command in the Dublin Fusiliers. In my Assistant Adjutant, Lt. B. Wolffe (whose tragic death in Palestine I shall relate in its proper place), I had an exceptionally gifted Jewish officer, hardworking, painstaking, conscientious, and all out in every way to make the Jewish Battalion a success. I tried to induce Senior Jewish officers to join the Battalion, but I found it very hard to get volunteers, for the Senior men preferred to remain in their own British Regiments. I was able to obtain the services of a fair number of Junior Jewish officers, and the Battalion gradually filled up in officers, N.C.O.'s and men. I would like to mention here that, although the great majority of all ranks were Jews, yet there were some Christian officers, N.C.O.'s and one or two men. In spite of this there was never the very slightest question between us of either race or religion. All eventually became animated with one spirit—the success, welfare and good name of this Jewish Battalion. I am glad to say that we had practically no crime to stain our record. There was not a single case of a civil offence being recorded against us all the time we were at Plymouth, which is something new in Army annals. And yet another record was created by this unique Battalion. The Wet Canteen, where beer only was sold, had to be closed, for not a single pint was drunk all the time it was open. The men showed wonderful quickness and aptitude in mastering the details of their military training. It came as a surprise to me to find that a little tailor, snatched from the purlieus of Petticoat Lane, who had never in all his life wielded anything more dangerous than a needle, soon became quite an adept in the use of the rifle and bayonet, and could transfix a dummy figure of the Kaiser in the most approved scientific style, while negotiating a series of obstacle-trenches at the double. I noticed that the men were particularly smart in all that they did whenever a General came along. I remember on one occasion, when we were about to be inspected, I told the men to be sure and stand steady on parade during the General Salute; I impressed upon them that it was a tradition in the British Army that, unless a Battalion stood perfectly steady at this critical moment, it would be thought lacking in discipline and smartness, and would get a bad report from the General. So zealous were my men to uphold this time-honoured tradition, that I verily believe that these wonderful enthusiasts for rigid British discipline never blinked an eyelid while the General was taking the salute. Certainly every Commander who inspected us always expressed his astonishment at the rock-like steadiness of the Jewish Battalion on parade. During our training period at Plymouth we received many kindnesses from the Jewish community there, more especially from its President, Mr. Meyer Fredman. In the long winter evenings we had lecturers who addressed the men on various interesting subjects. The famous and learned Rabbi Kuk of Jerusalem paid us a visit, and gave the men a stirring address on their duties as Jewish soldiers. Jabotinsky gave various lectures, one especially on Bialik, the great Jewish poet, being particularly memorable. We had many talented music-hall and theatrical men in our ranks; our concerts were, therefore, excellent, and our concert party was in great request throughout the Plymouth district. If there was one officer more than another who helped to promote the men's comfort, it was Lieut. E. Vandyk. He was in charge of the messing arrangements, and the Battalion was exceptionally fortunate in having a man of his experience to undertake this most exacting of all tasks. Later on Vandyk proved himself equally capable as a leader in the field, where he was promoted to the rank of Captain. I must not forget the kindness shown to us at Plymouth by Lady Astor, M.P., who gave us a Recreation Hut, and by Sir Arthur Yapp, the Secretary of the Y.M.C.A., who furthered our comfort in every possible way. While we were yet at Plymouth I received orders from the War Office to form two more Jewish Battalions in addition to the 38th. As soon as sufficient recruits justified it I recommended the Authorities to proceed with the formation of the 39th Battalion and to appoint Major Knowles, from the Depôt, to the Command. This was done, and from what I saw during the time I was in Plymouth, I felt quite confident that Colonel Knowles would make an excellent commander. Colonel Knowles was succeeded at the Depôt in London by Major Schonfield, who worked untiringly to promote the interests of the recruits, and to imbue them with a good, soldierly spirit while they were passing through his hands in Chenies Street. About the same time as Colonel Knowles was appointed, Captain Salaman so highly recommended his brother-in-law, Colonel F. D. Samuel, D.S.O., to me that I asked the Adjutant-General if this officer might be recalled from France to take charge of the training at Plymouth, and Jewish affairs there generally, after my departure for Palestine. The Adjutant-General very kindly agreed to my request, and transferred Colonel Samuel from France to Plymouth at very short notice. Soon after I left for Palestine recommendations were made to the War Office that it would be preferable to have a Jewish officer in command of the 39th Battalion, and the result was that Colonel Samuel was appointed to the 39th Battalion in the place of Colonel Knowles. This treatment was most unfair to the latter, who had worked extremely hard and enthusiastically, both at the Depôt and during the time he held command of the 39th Battalion, where he did all the spade work and made things very easy for his successor. Colonel Knowles afterwards went to France and later on served with the North Russian Expeditionary Force. Of course, it was all to the good to have a Jewish Commanding Officer, but it should have been arranged without doing an injustice to Colonel Knowles. About this time Major Margolin, D.S.O., a Jewish officer attached to the Australian Forces, was transferred to the Depôt at Plymouth, and eventually replaced Colonel Samuel in the command of the 39th Battalion. Outsiders will never be able to imagine the immense amount of trouble and detail involved in the formation of this unique unit. I must say that the War Office, and the local command at Plymouth, gave me every possible assistance. Colonel King, of the Military Secretary's Staff at the W.O., helped me through many a difficulty in getting Jewish officers brought back from France. Colonel Graham, also of the War Office, came to my assistance whenever he could possibly do so, while the late Military Secretary, General Sir Francis Davies, under whom I had served in Gallipoli, was kindness itself. General Hutchison, the Director of Organization, was always a tower of strength, and the Jewish Battalions owe him a heavy debt. Lieut.-Colonel Amery, M.P., and the late Sir Mark Sykes, M.P., also did what was in their power to make our thorny path smooth. The only serious trouble we had in Plymouth occurred over Kosher food. As most people probably know, Jewish food has to be killed and cooked in a certain way as laid down in Jewish Law, and it is then known as "kosher," i.e. proper. This was, of course, quite new to the Military authorities, and the Army being a very conservative machine, and, at times, a very stubborn one, they failed to see the necessity of providing special food for the Jewish troops—a curious state of mentality considering the care taken with the food of our Moslem soldiers. I have a fairly shrewd idea that all the blame for the trouble we were put to in this matter must not rest altogether on the shoulders of the Army officials, for I strongly suspect that our Jewish "friends," the enemy, who were so anxious to destroy the Jewishness of the Regiment, had their fingers in this Kosher pie! Now I felt very strongly that unless the Jewish Battalion was treated as such, and all its wants, both physical and spiritual, catered for in a truly Jewish way, this new unit would be an absolute failure, for I could only hope to appeal to them as Jews, and it could[40] hardly be expected that there would be any response to this appeal if I countenanced such an outrage on their religious susceptibilities as forcing them to eat unlawful food. I made such a point of this that I was at length summoned to the War Office by the Adjutant-General, Sir Nevil Macready, who informed me that I was to carry on as if I had an ordinary British battalion, and that there was to be no humbug about Kosher food, or Saturday Sabbaths, or any other such nonsense. I replied very respectfully, but very firmly, that if this was to be the attitude taken up by the War Office, it would be impossible to make the Battalion a success, for the only way to make good Jewish soldiers of the men was by first of all treating them as good Jews; if they were not to be treated as Jews, then I should request to be relieved of my command. Accordingly, as soon as I returned to Plymouth, I forwarded my resignation, but the G.O.C. Southern Command returned it to me for reconsideration. In the meantime a telegram was received from the War Office to say that the Kosher food would be granted, and Saturday would be kept as the Sabbath. After this things went smoothly; Sir Nevil Macready readily lent us his ear when I put up an S.O.S., and, as a matter of fact, he became one of our staunchest friends. I was more than gratified to receive, a few days later, the following "Kosher" charter from the War Office—a charter which helped us enormously all through our service, not only in England, but also when we got amongst the Philistines in Palestine.

14th Sept., 1917. Sir, With reference to Army Council Instruction 1415 of the 12th Sept., 1917, relating to the formation of Battalions for the reception of Friendly Alien Jews, I am commanded by the Army Council to inform you that, as far as the Military exigencies permit, Saturday should be allowed for their day of rest instead of Sunday. Arrangements will be made for the provision of Kosher food when possible.

I am, etc., Before we sailed for the front, General Macready did us the honour of coming all the way from London, travelling throughout the night, to pay us a friendly visit, without any of the pomp or circumstance of war, and he was so impressed by what he saw of the soldierly bearing of the men that, from that day until the day he left office, no reasonable request from the Jewish Battalion was ever refused. I had a final interview with General Macready at the W.O. before setting out for Palestine, when he told me in the presence of Major-General Hutchison, Director of Organization, that the object he aimed at was the formation of a complete Jewish Brigade, and that he was recommending General Allenby to commence that formation as soon as two complete Jewish Battalions arrived in Egypt. Of course, this was very welcome news to me, because it would mean all the difference in the world to our welfare and comfort if we formed our own Brigade. It would mean that the Brigade would have its own Commander who would be listened to when he represented Jewish things to higher authority. It would mean direct access to the Divisional General, to Ordnance, to supplies, and the hundred and one things which go to make up the efficiency and cater for the comfort of each unit of the Brigade. No worse fate can befall any Battalion than to be left out by itself in the cold, merely "attached" to a Brigade or a Division, as the case may be. It is nobody's child, and everybody uses it for fatigues and every other kind of dirty work which is hateful to a soldier. It can be imagined, therefore, how grateful I was to General Macready for promising a Jewish Brigade, for I knew that such a formation would make all the difference in the world to the success of the Jewish cause as a whole and, what was of great importance, to the good name of the Jewish soldier. Towards the end of January, 1918, we were notified that the 38th Battalion was to proceed on Active Service to Palestine. This news was received with great joy by all ranks, and every man was granted ten days' leave to go home and bid farewell to his family. Of course, our pessimistic friends took every opportunity of maligning the Jew from Russia, and said that the men would desert and we should never see a tenth of them again. I, however, felt otherwise, and had no anxiety about their return. Nor was I disappointed, for when the final roll-call was made there were not so very many absentees, certainly no more than there would have been from an ordinary British battalion, so here again our enemies were confounded and disappointed, for they had hoped for better things. The Battalion was ordered to concentrate at Southampton for embarkation on the 5th February. Two days before this date Sir Nevil Macready ordered half the Battalion to come to London to march through the City and East End, before proceeding to Southampton. This march of Jewish soldiers, unique in English military history, proved a brilliant success. The men[44] were quartered in the Tower for the night, and on the morning of the 4th February started from this historic spot, in full kit and with bayonets fixed, preceded by the band of the Coldstream Guards. The blue and white Jewish flag as well as the Union Jack was carried proudly through the City amid cheering crowds. At the Mansion House the Lord Mayor (who had granted us the privilege of marching through the City with fixed bayonets) took the salute, and Sir Nevil Macready was also present to see us march past. As we approached the Mile End Road the scenes of enthusiasm redoubled, and London's Ghetto fairly rocked with military fervour and roared its welcome to its own. Jewish banners were hung out everywhere, and it certainly was a scene unparalleled in the history of any previous British Battalion. Jabotinsky (who had that day been gazetted to a Lieutenancy in the Battalion) must have rejoiced to see the fruit of all his efforts. After a reception by the Mayor of Stepney, the march was resumed to Camperdown House, where the men were inspected by Sir Francis Lloyd, G.O.C. London District. He complimented them on their smart and soldierly appearance, and made quite an impressive speech, reminding them of the heroism and soldierly qualities of their forefathers, and concluded by saying that he was sure this modern Battalion of Jews now before him would be no whit behind their forbears in covering themselves with military glory. Afterwards the troops proceeded, amid more cheering, to Waterloo, where, before they entrained for Southampton, they were presented by Captain Fredman with a scroll of the law. My new Adjutant, Captain Leadley, who came to take the place vacated by Captain Neill on promotion to Major, had only just joined us on the morning of our march. He was much surprised at the first Regimental duty he was called upon to perform, which was to take charge, on behalf of the Battalion, of the Scroll of the Law. The excellent Jewish Padre who had just been posted to us, and whose duty this should have been, was with the remainder of the troops at Plymouth. I was very favourably impressed by Captain Leadley from the first moment I saw him, and during the whole time he remained with the Battalion I never had cause to change my opinion. He was a splendid Adjutant, and, in my opinion, was capable of filling a much higher position on the Army Staff. When the half Battalion reached Southampton, it joined forces with the other half, which had been brought to that place from Plymouth by Major Ripley, who was now Second-in-Command in place of Major MacDermot, who remained behind with the Depôt. The whole Battalion proceeded to embark on the little steamship Antrim on the 5th February. Just as Captain Salaman was about to go on board, he was confronted by another Medical Officer, Captain[46] Halden Davis, R.A.M.C., who, at the last moment, was ordered by the War Office to proceed with us instead of Captain Salaman. I knew nothing about this, and was naturally loth to lose Captain Salaman, while he, on his part, was furious at the idea of being left behind. However, there was no help for it, so back he had to go to Plymouth. I think a certain number of the shirkers in the Battalion may have been pleased to see him go, for he stood no nonsense from gentlemen of this kidney. I had, for some time, been making strenuous efforts to obtain the services of the Rev. L. A. Falk, the Acting Jewish Chaplain at Plymouth, as our spiritual guide, and luckily I was successful, for, at the last moment, all difficulties were surmounted, and he joined us as we embarked. I had had many warnings from people who ought to have known better that he was not a suitable man for the post, but I had seen him and judged for myself, and I felt sure that he would suit my Jews from Russia much better than a Rabbi chosen because he was a Jew from England. His work and his example to others, during the whole time he served with us, were beyond all praise, and I often felt very glad, when he was put to the test of his manhood, that I had not listened to the voice of the croaker in England. The embarkation of the Battalion was complete by 5 p.m. on the 5th February, and after dark we steamed out of the harbour and made for Cherbourg. It is fortunate that we escaped enemy submarines, for the little Antrim was packed to its utmost limits, not only with the Jewish Battalion, but also with other troops. We were kept at the British Rest Camp at Cherbourg until the 7th, and then entrained for St. Germain, near Lyons, where we rested from the 9th to the 10th. From here we went on to Faenza, along the beautiful French and Italian Riviera. The behaviour of the men during the whole long journey of nine days was exemplary, and I wired a message to this effect to the War Office, for, as Russia was just out of the War, there was some anxiety in England as to how Russian subjects in the British Army would behave on hearing the news. As a matter of fact recruiting of Russian Jews in England had been stopped after we left Southampton, and many of the men naturally questioned the fairness of the authorities in freeing slackers or late comers, while retaining those who had promptly answered the call. I cabled this point of view to the Adjutant-General on reaching Taranto and received a reply that all such matters could be settled in Egypt. We remained basking in the sunshine of Southern Italy for over a week. I met here an old friend of mine, Captain Wake, who had been badly wounded in one of our little wars on the East African coast many years ago. Although minus a leg he was still gallantly doing his bit for England. We were encamped at Camino, a few miles from Taranto, and our strength at this time was 31 officers, and roughly 900 other ranks. Two officers and about 70 N.C.O.'s and men sailed on another boat from Marseilles, with the horses, mules and wagons, under the command of Captain Julian, M.C. While we were at Taranto the Rev. L. A. Falk and I, accompanied by Jabotinsky, searched for and eventually found a suitable Ark in which to place the Scroll of the Law. At the close of our last Sabbath service before we embarked, I addressed the men, and, pointing to the Ark, told them that while it was with us we need have no fear, that neither submarine nor storm would trouble us, and, therefore, that their minds might be easy on board ship. We embarked on the Leasoe Castle at 9 o'clock a.m. on the 25th, steamed out of the harbour in the afternoon, under the escort of three Japanese destroyers, and arrived safely in Alexandria on the 28th February, never having seen a submarine or even a ripple on the sea throughout the voyage. Owing to this piece of good luck my reputation as a prophet stood high! It is a curious fact that on her next voyage the Leasoe Castle was torpedoed and sunk." Colonel Patterson later became great friends with the Netanyahu family and was godfather to Yonathan Netanyahu, who was named in honor of Patterson. Yonathan - killed in the famous rescue raid of Jewish hostages in Entebbe, Uganda, in 1976 - was the brother of the recent Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu. Review of his biography The Seven Lives of Colonel Patterson |

Empire in Your Backyard: Plymouth Article | Significant Individuals | Crownhill Fort and the Jewish Legion | Charles Orr's Memoirs

Armed Forces | Art and Culture | Articles | Biographies | Colonies | Discussion | Glossary | Home | Library | Links | Map Room | Sources and Media | Science and Technology | Search | Student Zone | Timelines | TV & Film | Wargames