|

|

|

|

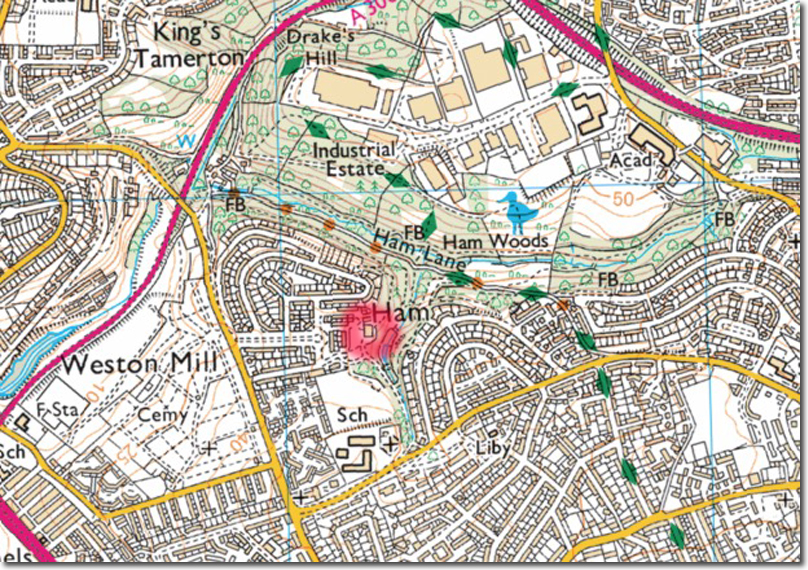

Too many of Plymouth’s old manor houses have sadly fallen foul of the developers or of hostile local councils through the years. Fortunately, one that still survives is Ham House on the edge of the Ancient Woodland of Ham Woods. Indeed, this part of Plymouth looks very much as it would have when the house was constructed by Robert Trelawney in 1639. Unbeknownst to Robert, this would mean that the House would be built just in time for the travails of the English Civil War which broke out in earnest just a couple years later and indeed the house would find itself very much in the middle of those momentous events. Robert Trelawney had been mayor of Plymouth since 1633 and in 1640 he was elected to Parliament on behalf of the Borough of Plymouth. Now this is intriguing in that Robert was a supporter of King Charles and an affirmed Royalist and yet Plymouth would soon declare itself very strongly for Parliament. It is something to Robert’s credit that he was regarded as a fair and open minded man and one that was doing his utmost to smooth relations between the Royalists and Parliamentarians. He also had substantial interests in the Plymouth Company in the New World and was heavily involved in the early settlement of Maine Colony. However in the febrile atmosphere of a country hurtling towards Civil War in 1642, he was overheard to declare that Parliament had no right to appoint a military guard against the King of England. Bearing in mind that this was just a couple weeks after the King had tried and failed to arrest 5 MPs in the House of Commons, this was tantamount to saying that the King was correct in trying to impose his will on Parliament. As a consequence, Parliament ordered Trelawney’s arrest and imprisonment in London. Being a committed Royalist he did not deny that he said those words and so was expelled from the House of Commons. He was released for a short while and returned to Plymouth to put his affairs in order. However, as war got underway those tasked with defending Plymouth for Parliament sent out patrols to gather in food and to destroy and pillage houses of known Royalist supporters. This included Ham House of course. Parliamentarian cavalrymen swept down on the house and emptied it of everything of value that could be transported back by horse. Soon after this attack, Sir Ralph Hopton, the Royalist Commander given orders to seize and take Plymouth for the King, moved troops across the Tamar and from the South Hams to occupy Widey House, Knackersnowle village and Ham House. The Royalists started to build defences of their own around these three locations. Ham House was now set to guard against Parliamentarian troops attempting to secure supplies through crossing the river at Weston Mill. Robert Trelawney was still attempting to counsel the people of Plymouth against standing against the King. Parliament’s patience snapped and Robert was arrested for a second time on November 23rd 1642. He was duly sent by ship to London and kept as a prisoner in Winchester House along the River Thames. Some local people felt pity for their previous mayor and MP and lobbied for his release. However, his fate was sealed when three ships of his sailed from Plymouth full of precious weapons and foodstuffs. The Masters had claimed that they were going to join the Parliamentary Navy but in fact they sailed directly to the Royalist controlled port of Falmouth. The supplies were very much welcomed by the King’s forces and would soon be used against Plymouth no less. Robert Trelawney would never see freedom again and would die in Parliamentary custody in London in 1644.

Ham House though continued to play an important role in the war even without its owner. As Cornwall and much of Devon declared firmly for the King, Plymouth’s situation appeared precarious especially as the earthworks along the ridge line from Mount Gould to Pennycomequick and down to Stonehouse were far from complete. Seeking to buy time to gather more troops and build more extensive fortifications, the Parliamentarian commander, the Earl of Stamford, asked for a conference to discuss whether Devon and Cornwall might declare neutrality in the war. The venue for this conference was to be Ham House no less. Sir Ralph Hopton took the bait and met Sir George Chudleigh and Francis Buller who were acting on behalf of Stamford on January 29th 1643 at the house. The proposal was that Devon and Cornwall stay neutral but that anyone within those two counties could still volunteer to fight for either side, but would have to travel outside the counties to do so. Hopton also recommended that all defences and forts be dismantled which was something the Plymouth defenders were loathe to concede. After an hour and a half of debate, the Parliamentarians withdrew empty handed. They understood that dismantling their fortifications would be tantamount to surrender and something they could not contemplate. They had however, bought more time for those very same defences to be constructed and so Stamford was not entirely disatisfied with the meeting. Sir Ralph Hopton had been so taken with the venue that he decided to move his headquarters to Ham House itself and make it the base of his operations for the first investiture of Plymouth. I won’t go into the details of the almost four year long siege of Plymouth that saw at least three major assaults on the town including one from King Charles himself. Suffice it to say that Ham House was mostly in the Royalist camp for most of that period. However, a major Parliamentarian assault on St. Budeaux early in 1644 saw that battle unfold at Ham House where Royalists tried to fend off the far larger than usual sortie coming out of Plymouth. They fought from Ham House down to Weston Mill and then up to St. Budeaux Church. Unfortunately for the Parliamentarians most of their cavalry got lost in Ham woods after taking an incorrect turning. This meant that they could not follow up on the Parliamentarian’s victory and much of the Royalist force could escape. Ham House continued to be a key centre point for the Royalists even as their forces were whittled away as the war as a whole turned against them. Parliamentarian cavalry would increasingly comb the area looking for supplies or for unwary Royalists not expecting to be set upon. These patrols were also always on the lookout for new horses to bring back as mounts into Plymouth as they had few replacements of their own. Their favourite hunting grounds were the country houses inhabited by known Royalist sympathisers such as at Kinterbury, Warleigh, Widey, Roborough and of course Ham House. Unluckily for Ham House, it was torched at least once more by Parliamentarian forces on a lightening raid. Quite remarkably Plymouth held out for Parliament for the entire duration of the war. In fact it was not until March 21st 1646 that Oliver Cromwell and Thomas Fairfax marched into Plymouth at the head of a relieving force and to the delight of the long suffering Parliamentarian defenders. Plymouth had survived for four long years. Ham House was significantly remodelled in the 18th and 19th Centuries, but its essential footprint is much as it would have been in 1639. It was a Royalist house within striking distance of the only Parliamentarian stronghold in the Westcountry that never capitulated. As a consequence, Ham House had a very eventful war and the sight of armed Royalist or Parliamentarian cavalry galloping up or down the driveway to Ham House or through the woods behind would have been an all too common sight. If you listen carefully, you may still hear the thud of their hooves or the clinking of their bridles and catch a glimpse of the riders straining their necks as they nervously survey the woods for an enemy that may strike them at any moment. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Empire in Your Backyard: Plymouth Article

Armed Forces | Art and Culture | Articles | Biographies | Colonies | Discussion | Glossary | Home | Library | Links | Map Room | Sources and Media | Science and Technology | Search | Student Zone | Timelines | TV & Film | Wargames