|

|

|

|

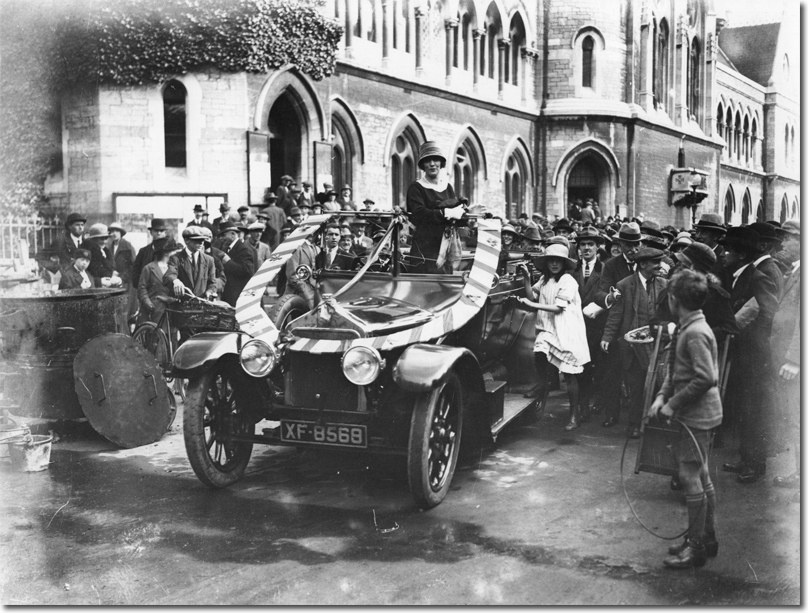

This photograph shows Nancy Astor on the campaign trail outside the Municipal Offices in Plymouth during the 1924 General Election.

In 1906, Nancy married Waldorf Astor, later second Viscount Astor (1879–1952), the son of the eccentric millionaire William Waldorf Astor. Nancy energetically supported Waldorf's political career by canvassing and organizing the Primrose League in Plymouth, where he became one of the two members in 1910. But her role was essentially conventional; she showed little interest in women's suffrage or in an independent career for herself. She became famous as a hostess at Cliveden, their magnificent country house perched above the Thames at Taplow, and at St James's Square where she liked to pose at the top of the staircase, sparkling with jewels, to welcome her guests. She made a point of inviting men and women with whom she disagreed, such as Sylvia Pankhurst, the socialist and suffragette, and Winston Churchill, who detested the entry of women into the House of Commons. It was at breakfast at Cliveden that the famous, though perhaps apocryphal, exchange occurred when Nancy commented: 'Winston, if I was married to you I'd put poison in your coffee.' He replied: 'Nancy, if I was married to you I'd drink it.'

As a Conservative of liberal views, Waldorf became increasingly associated with David Lloyd George during the First World War. But his own promising career suffered a setback in October 1919 when he succeeded to his father's viscountcy. He made it known that he intended to divest himself of the title and meanwhile promoted Nancy as a stop-gap candidate in the by-election at Plymouth Sutton. At this point no woman had sat in the House of Commons, and prejudice ran high; even the tory party chairman, Sir George Younger, complained about her candidacy: 'the worst of it is, the woman is sure to get in'. A defeat for Nancy at Plymouth would have set back the cause of women MPs for many years. In the event she managed to overcome the prejudice by posing as a loyal wife and by denying any intention of seeking a career in politics: 'I am not standing before you as a sex candidate. I do not believe in sexes or classes'. The newspapers, which appreciated her lively exchanges with hecklers, treated her sympathetically, and the working-class voters who dominated the constituency were fascinated to find a wealthy and titled lady who had the common touch. She was also a little lucky in that public opinion—which had given the Lloyd George coalition a huge majority only a year earlier—had not yet become disillusioned with the prime minister. In a three-cornered contest she retained 51 per cent of the vote and was elected with a majority of 5000. When she took her seat on 1 December 1919 she was introduced by Lloyd George and Arthur Balfour. Nancy's triumph did not lead to a flood of women MPs, but it encouraged other Conservative wives to step into their husbands' shoes, and it put pressure on the Labour Party to get its leading women into parliament. Nancy adapted well to the adversarial style of the House of Commons, becoming notorious for her frequent interruptions of other members. However, she suffered from an inability to deliver a substantial and well-considered speech and her performances degenerated into heckling matches. In time members found her rather tedious, though her liveliness was always appreciated. Her greatest success as a politician came in 1923 when she promoted legislation to ban the sale of alcohol to anyone under eighteen. However, in view of the introduction of prohibition in the United States, Nancy's enthusiasm for temperance was a political liability. Although it helped her to attract Liberal votes, it provoked the brewing interests into running an independent candidate against her who split her vote and sharply reduced her majority at the 1922 election. She rammed home the message that the new female electorate was more interested than the pre-war one in social questions, and in his administration of 1924–9 Stanley Baldwin showed himself alive to this change. However, Nancy was never offered a government post, and in 1924 she was passed over in favour of the duchess of Atholl. Though officially a Conservative, she never hid her ambivalent attitude towards the party, yet at the same time her attacks on the Labour Party made it difficult for her to emerge as an independent politician. That she had some aspirations to lead a women's party was shown after the general election of 1929, when she tried to co-ordinate the efforts of the fourteen women members in parliament; however, the nine Labour women saw nothing to be gained and the initiative failed. Her majority over Labour had been cut to barely 200 votes in 1929 but the popularity enjoyed by the National Government in 1931 and 1935 kept her safely in parliament. Like many people at that time Waldorf and Nancy were appeasers in the sense that they believed that Germany had been treated harshly by the treaty of Versailles; she also had connections with influential people such as Philip Kerr who was active as an emissary to Hitler. However, the idea of Cliveden as the centre of a conspiracy to impose appeasement is regarded as essentially a fiction. Nancy's guests included a wide range of politicians including leading opponents of appeasement. When she invited von Ribbentrop to lunch, at Kerr's suggestion, they got on badly and her name ended up on a Nazi list of people to be arrested in the event of a German invasion. However, despite her repeated denials, the charges gained wide credibility due to speculation in the press and the cartoons by David Low. By 1939 she was becoming a liability to her party, though her reputation was partly restored by her courage and patriotism during the Second World War. She joined the Conservative rebels in forcing Neville Chamberlain from office in May 1940, and throughout the war she and Waldorf devoted much of their time to raising morale in Plymouth, where he served as mayor for five years. Plymouth became a major target of attack and the Astors' house suffered damage from incendiary bombs. During the blitz Nancy became famous for performing cartwheels to entertain sailors and leading the dancing on the Hoe each evening. The city made her an honorary freeman in 1959 in recognition of her long service; this was one of very few honours she received for her public work. Despite her wartime popularity in Plymouth, Waldorf advised Nancy that she would be defeated if she contested the general election in 1945, and he took it upon himself to inform her local association that she would stand down. Though she agreed, she resented his intervention, and their relations became more distant during the years leading to his death in 1952. She found it difficult to adjust to being out of the limelight after so many years. Nancy fell ill in spring 1964 when staying with her daughter, who was now the countess of Ancaster, at Grimsthorpe Castle, Bourne, Lincolnshire. She died there on 2 May and was buried at Cliveden beside Waldorf. A memorial service was held on 13 May in Westminster Abbey. by Martin Pugh |

Empire in Your Backyard: Plymouth Article | Significant Individuals

Armed Forces | Art and Culture | Articles | Biographies | Colonies | Discussion | Glossary | Home | Library | Links | Map Room | Sources and Media | Science and Technology | Search | Student Zone | Timelines | TV & Film | Wargames