|

|

|

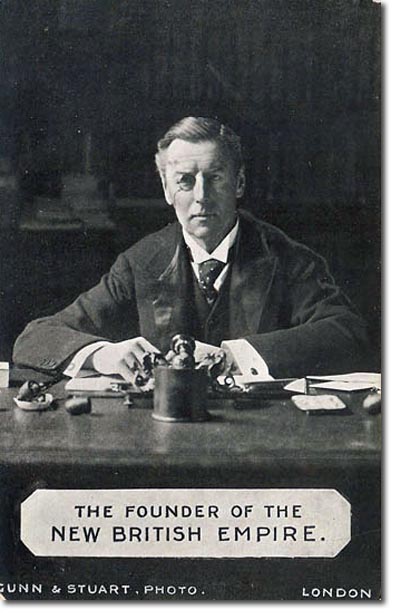

| Few politicians sacrificed so much for the imperial cause! Joseph Chamberlain was a renowned liberal politician with a reforming record in Birmingham. He would eventually split and then leave the Liberal party over their imperial policies. He became the standard bearer for late 19th Century Imperialism and came close to leading the Conservative party on the back of these policies.

Chamberlain was a successful manufacturer, who embarked on a full-time political career after making a fortune in his adopted city, Birmingham. He was not the first individual to move from the world of business to national politics, but he was unusual in two respects. He was determined not only to be treated as an equal by the landowning elite which still dominated Victorian cabinets, but also to acquire a definite influence over policy making. Chamberlain was an effective organiser, first gaining national prominence in 1869 as the driving force behind the National Education League. This articulated the militant Nonconformist demand for state funded, universal, non-denominational primary schooling, and clashed with the first Gladstone government over the pro-Anglican bias of its 1870 Education Act. Although it failed to achieve its immediate objective, the League signalled a broader intention on the part of Chamberlain, to mobilise support for a bid to radicalise the Liberal party's policy agenda. His real aim was to subvert the leadership of Gladstone and his aristocratic Whig allies, and to adopt policies which would challenge Britain's traditional landed establishment. Following a period as a reforming Mayor of Birmingham, during which he took key services into public ownership and initiated a bold scheme of urban development, Chamberlain secured election as one of the city's MPs. In 1877 he set up the National Liberal Federation, a Birmingham-based body which sought to unite the many local Liberal Associations which had emerged in large centres of population in mid-Victorian Britain. The existence of the Federation helped to propel Chamberlain into Gladstone's second cabinet as President of the Board of Trade, following the Liberal general election victory of 1880. After only four years in the House of Commons, this was a significant personal achievement. Nonetheless, as modern research has made clear, this did not mean that Chamberlain was able to head a united and irresistible radical movement. Although the National Education League attracted a great deal of publicity, by 1873 it was clearly backing away from a direct confrontation with the Gladstone government. Chamberlain nurtured an enduring sense of antagonism towards W.E. Forster, the minister responsible for the 1870 Education Act, regarding him as a former radical who had compromised his principles for the sake of office. Yet this is surely paralleled, a decade later, by Chamberlain's own decision to take a relatively junior post in a Gladstone administration dominated by Whigs and moderates. Between 1880 and 1885, with the government buffeted by troubles in Ireland and the empire, Chamberlain struggled to make his mark as a departmental minister. His personal contribution to its most significant domestic achievement, the extension of the vote to rural householders in 1884, was very limited. The collapse of the ministry a year later liberated Chamberlain to devise an 'unauthorised programme' of his own. In the November 1885 general election he offered the electorate a range of radical policies, including proposals for free education, Church disestablishment and smallholdings for agricultural labourers. His programme alarmed moderates without attracting significant working-class support, and the Liberals did particularly badly in the urban areas, which they regarded as their natural constituency. This was a severe personal disappointment for Chamberlain. Breaking with Gladstonian Liberalism Few people can have expected that, within a few months of the 1885 electoral disaster, Gladstone would have returned to office with the support of the Irish Nationalist party, ready to bring forward proposals for Home Rule. Fewer still would have anticipated that, in the ensuing division within the Liberal camp, Chamberlain would be found alongside his former Whig opponents, standing in opposition to the party leader's plans to grant a legislative assembly to Ireland. In office prior to 1885, Chamberlain had aligned himself with the advocates of conciliation and had proposed a limited degree of devolution, in the form of an Irish 'central board'. This apparent inconsistency explains why many Liberals accused Chamberlain of being a self-interested conspirator, who was motivated by personal ambition rather than genuine attachment to principle. Chamberlain's reasons for breaking with his old leader have aroused a great deal of controversy. He maintained that he was not opposed to the principle of Home Rule, but to the particular form in which Gladstone intended to grant it. Specifically, Chamberlain condemned the proposal to remove Irish MPs from the Westminster Parliament, insisting that this would lead to the separation of the two countries and the break-up of the United Kingdom. He also emphasised his opposition to Gladstone's Land Purchase Bill, which was originally to accompany Home Rule. He argued that this was a misguided and expensive attempt to resolve the agrarian problems of Ireland, which would use British taxpayers' money to buy out undeserving Irish landowners. Certainly Chamberlain conducted his campaign against Home Rule with an eye to what was electorally popular. Perhaps he expected a defeated, ageing Gladstone to withdraw from the Liberal leadership, leaving the field clear for a dynamic radical successor. There seems little doubt that Chamberlain was angered by Gladstone's offer of a second minor Cabinet post, the Local Government Board, in February 1886. He may also have felt frustrated by the way in which Gladstone seemingly used Irish issues to drive domestic reforms off the party's agenda. The Home Rule crisis demonstrated the insecurity of Chamberlain's hold on rank and file Liberal loyalties. Although he managed to retain his own electoral base in the West Midlands, the party overwhelmingly sided with Gladstone. Chamberlain's own creation, the National Liberal Federation, abandoned him and symbolically moved its headquarters from Birmingham to London. In part this reflected the ingrained loyalty of party activists to the official leadership, but the comments of Liberal speakers up and down the country, in the course of the election campaign, suggested deeper misgivings about Chamberlain's motives and character. In a party heavily influenced by the evangelical outlook of Nonconformity, Gladstone's ability to project a sense of moral mission gave him a decided advantage over the materialistic Chamberlain. The latter's religious faith had evaporated as a result of personal tragedy - he had lost two wives at an early age - and his politics was devoid of the 'spiritual uplift' generated by the Grand Old Man. The verdict of the Pall Mall Gazette, reporting on the reactions of party members in Manchester, was typical of comment in the Liberal press: 'the Premier [Gladstone] satisfies their aspirations after liberty, justice and righteousness, as neither Mr Chamberlain nor any other man can'. For all his efforts to devise practical reform programmes, Chamberlain had never fully grasped the need to appeal to Liberal supporters' hearts, as well as to their reason and their self-interest. The events of 1886 placed Chamberlain in a difficult position. The abortive 'round table' conference of January-February 1887 - a series of meetings between Chamberlain and representatives of Gladstone - demonstrated the impossibility of a return to the Liberal fold. Chamberlain could not accept his former leader's view of Home Rule as a litmus test of Liberal identity. He toyed with the idea of forming a new centre party but this came to nothing. As a Liberal Unionist he found himself in a parliamentary grouping which was dominated by Whigs under the leadership of Lord Hartington. Radical Unionists like Chamberlain formed a small proportion of the rebel group of MPs. His political future lay in support for Lord Salisbury's Conservative government, which had come into being following the defeat of Home Rule in the 1886 general election. A shared commitment to the Union with Ireland was the glue that bound together these former enemies. Chamberlain could not, however, at first afford to associate too closely with the Conservatives. Unqualified support for Salisbury, the embodiment of aristocratic, Anglican values, would damage his radical credentials and threaten his support base in Birmingham. The solution was for Chamberlain to demonstrate his influence over the Conservatives by persuading them to adopt a reformist position on non-Irish issues. The introduction of elected county councils in 1888, and of free elementary education in 1891, in part indicated the Conservative government's responsiveness to its radical Unionist supporter. Salisbury recognised Chamberlain's worth as a parliamentary ally, a platform speaker and a source of support for Unionism in his West Midlands stronghold. Chamberlain's influence should not, however, be exaggerated. He did not become the overall leader of the Liberal Unionist members of the Commons until the end of 1891, when Hartington moved to the Lords on inheriting the title of Duke of Devonshire. No attempt was made to meet Chamberlain's wishes on the details of legislation; for example the county councils were denied powers, such as control over the police, for which he had contended. It is also worth noting that other reasons, particularly a wish to forestall more far-reaching changes by a future Liberal administration, figured in Salisbury's decision to undertake reforms. Building and Dividing Unionism Chamberlain's decision to take office in Salisbury's next government, in the summer of 1895, was the logical culmination of his political evolution since the Home Rule crisis. He was one of a small number of leading Liberal Unionists who were invited to join a Conservative-dominated cabinet. This step affirmed his prominence in what had come to be known as the Unionist alliance. It was significant, however, that he opted for the Colonial Office in preference to one of the more senior posts that were available, such as the Home Office or the Exchequer. No doubt his choice reflected an interest in developing the resources of the empire, which had been steadily growing since his breach with Gladstonian Liberalism. It also indicates Chamberlain's awareness that, in one of the leading domestic policy departments, he would probably have found himself at variance with his Conservative colleagues. Although he played a leading role in passing the 1897 Workmen's Compensation Act, for the most part Chamberlain suppressed his enthusiasm for constructive social reforms. Imperial issues afforded a more promising basis for co-operation with his partners in government. Yet even here, he was to find that he had different priorities from his new associates. His ambitious plans for investment in Britain's colonies in the West Indies - the so-called 'undeveloped estates' - were frustrated by the Conservative Chancellor of the Exchequer, Sir Michael Hicks Beach, who was unwilling to provide the necessary funding. The central event of Chamberlain's tenure of the Colonial Office was the Anglo-Boer War, waged from 1899 to 1902. He played a key role in the events leading to its outbreak and was the central figure in the so-called 'khaki election', called by Salisbury in September 1900 in order to win a second term of office. Chamberlain made a straightforward appeal to patriotic, imperial feeling, portraying the Liberal opposition as sympathisers with Britain's Boer enemies in South Africa. In the words of a former admirer, Beatrice Webb, he 'played it down low to "the man in the street"'. The campaign, which took place against a background of initial British military victories, in many ways represented Chamberlain's high water mark. The appeal of imperialism was to be tainted by the way in which the war dragged on for a further 19 months. British forces had to resort to farm burning and the use of concentration camps in order to bring about the final collapse of Boer resistance. In July 1902 the ageing Salisbury made way for his nephew, Arthur Balfour, as Prime Minister. By then the fortunes of the Unionists, and of Chamberlain in particular, had begun to ebb. They had few positive domestic achievements to bring before the electorate. Chamberlain was the first senior politician to take up the issue of old age pensions, but the cost of the Anglo-Boer War ruled out such a break with the traditions of the Victorian minimalist state, at least for the time being. Balfour's 1902 Education Act antagonised Nonconformists by granting local rate support to church schools. This was a major political blunder, against which Chamberlain warned in vain. The frustrations of early twentieth-century Unionism help to explain Chamberlain's decision, in 1903, to launch a new initiative in the form of a campaign for tariff reform. He proposed to break with more than half a century of free trade by imposing taxes on foreign imports but granting preferential treatment to empire countries. The policy was intended to meet a number of requirements: to protect vulnerable sectors of the economy against foreign competition; to win working-class support by generating both employment and funding for social reform; and above all to provide a means of binding together the members of Britain's world-wide empire. Tariff reform captured the imagination of many Unionist party activists, who saw its potential as a way of seizing control of the political agenda. Its immediate effects, however, were disastrous for the party. Unionists divided between enthusiastic Chamberlainite 'whole-hoggers', pragmatists who favoured a more restricted policy of tariff retaliation, and diehard supporters of free trade. A crucial weakness of tariff reform was the requirement to impose a tax on food imports. The cry of 'the dear loaf' enabled the Liberals to present themselves as defenders of the working classes, against the threat of a rise in the basic cost of living. Weakened by division, the Unionist party experienced one of its most crushing electoral defeats in the 1906 contest. Shortly afterwards a stroke removed Chamberlain from the front rank of British politics. The Legacy Chamberlain's dogmatic adherence to his tariff reform programme illustrated his limitations as a politician. For such an avowed populist, he demonstrated a remarkable insensitivity to the feelings and values of the wider electorate. He believed that the promise of a strong economy, and the vision of imperial unity, would carry the day; and he underestimated the deep-rooted moral appeal of free trade. Perhaps, as the historian Alan Sykes has argued, a constructive radical policy like tariff reform was simply too alien to the traditions of British Conservatives. They were more comfortable with an essentially negative posture based upon the defence of private property, the Union with Ireland and other institutions. Even in Chamberlain's own lifetime, the party leadership backed away from wholehearted support for his policy, by promising in January 1913 that a Unionist government would not introduce tariffs without holding a second general election. In 1932 his younger son, Neville, as Chancellor of the Exchequer in the National Government, helped to negotiate the Ottawa agreements, a partial realisation of imperial preference. The agreements fell short of the grand vision of Joseph Chamberlain a generation earlier. They comprised a series of bilateral deals between Britain and the self-governing Dominions, in which the participants were mainly concerned with their separate economic interests. Chamberlain left his mark on the next generation of Unionist leaders. Andrew Bonar Law and Stanley Baldwin both acknowledged him as an inspiration; and his devoted sons, Austen and Neville, also led the party with differing degrees of success. Yet the tone of the party in the inter-war period, and indeed for the greater part of the Twentieth Century, was very different from the one that he had set as a strident champion of empire. It was much less confrontational and more inclined to seek compromise. British Conservatism was not to be led in a radical, crusading manner until the advent of Margaret Thatcher; and by then, of course, the political context had changed beyond recognition. |

Armed Forces | Art and Culture | Articles | Biographies | Colonies | Discussion | Glossary | Home | Library | Links | Map Room | Sources and Media | Science and Technology | Search | Student Zone | Timelines | TV & Film | Wargames