|

|

|

|

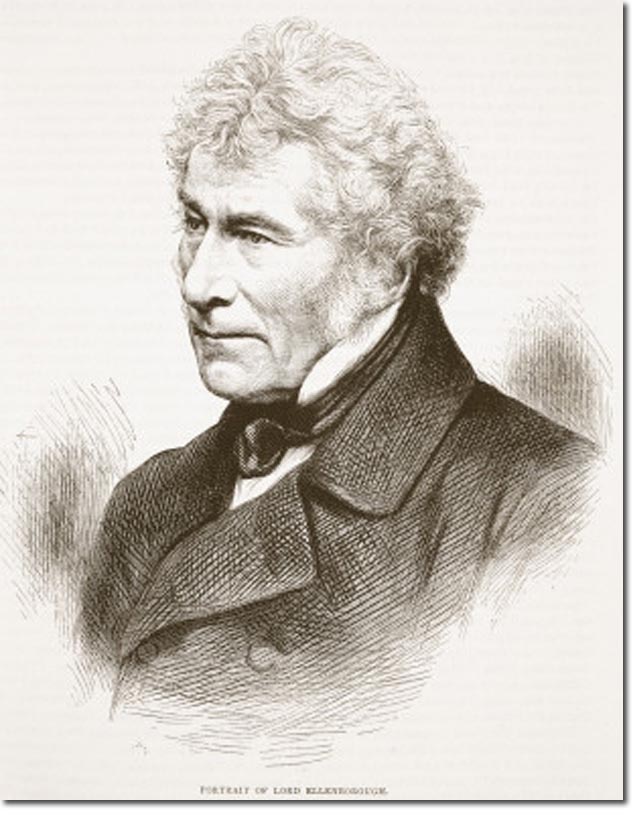

Lord Ellenborough replaced Auckland as Governor General of India. He was already determined to evacuate Afghanistan even before he was aware of the massacre of Elphinstone's army in Kabul. As far as was concerned, the whole enterprise was a drain on resources and exposed Britain's position strategically. Ellenborough's numerous critics recognized, eventually, the magnitude of his achievement in restoring Britain's prestige after the unprecedented disaster. From Calcutta he directed the regrouping of the remaining British garrisons in Afghanistan. Moving up country to Allahabad, he was able to order an advance on Kabul in July. His generals received instructions that emphasized political as well as military realities, and were accordingly criticized for excessive caution. It was vital for the sepoys' morale to re-establish and maintain 'the feeling of superiority' over their Afghan foes. Successful actions at several points were a necessary prelude to the advance.

He insisted that political officers on the frontier wedded to Auckland's policy should be subordinated to the military commanders. There could be no question of permanently occupying Afghanistan. Kabul fell to the British in September 1842; its bazaar was burnt and a handful of prisoners in the hills liberated. The victorious army withdrew, bringing with it a trophy, the gates of the famous Hindu temple of Somnath, carried off by a medieval Muslim invader. Ellenborough was convinced that the Muslim minority in India, her former rulers, sympathized with the Afghans. His prize, the authenticity of which was disputed, served to advertise their disappointment and remind the Hindu majority of 'the security of their religion under British rule'. Ellenborough's proclamation of 1 October 1842 combined fulsome praise of the army with a statement of policy. Abandoning the Afghans to 'the anarchy which is the consequence of their crimes', the government of India would be content with the frontier to the north-west as it was. 'Pacific and conservative' in its foreign policy, it intended to devote the expenditure saved by retiring from 'a false military position' to 'the improvement of the country and the people'. British and Indian soldiers had demonstrated their superiority to potential enemies. As Ellenborough was well aware, this proclamation, and a second on 4 October announcing the return of the gates of Somnath, invited attack in Britain. In his defence, he dwelt on the isolation of the British in India, the 'painfully evident' indifference of the masses to their rulers, the unwise treatment of Indian princes and of Hindu susceptibilities, and the neglect of public works 'indicating greatness, and liberality'. The language of the proclamation was meant, he told the East India directors, to 'give our Government a national character... to make the people feel... it exists not for the English only, but for them'. The Peel ministry, and Wellington in particular, stood by him in the face of derision from the Whigs, furious at the aspersions on their policy and governor-general. There was even talk of impeachment: but a reaction set in on the publication of the blue book containing his dispatches, and he received the thanks of parliament for his services. Politicians and newspapers recognized the force of his contention that 'British power in India... is in a state of constant peril'. The situation had forced him to rebuild the morale of 'a defeated army' by giving them victories and welcoming them back with much fanfare. |

First Afghan War | Significant Individuals

Armed Forces | Art and Culture | Articles | Biographies | Colonies | Discussion | Glossary | Home | Library | Links | Map Room | Sources and Media | Science and Technology | Search | Student Zone | Timelines | TV & Film | Wargames