|

|

|

|

Obituary from The Times

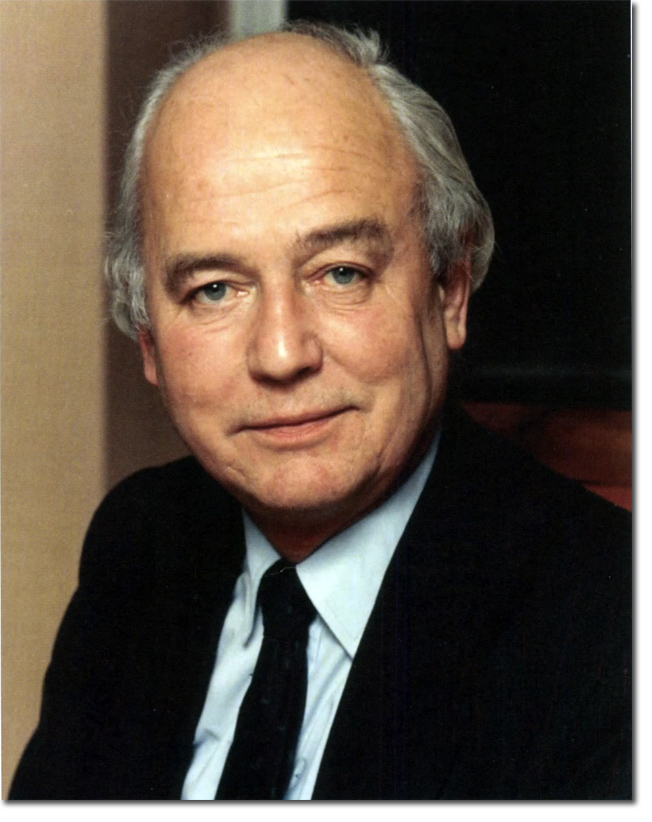

2 August 1929 - 24 February 2017 It was probably as an avowed hanger and flogger that Lord Waddington was best known, delighting Conservative Party conferences with his calls for the reinstatement of the death penalty. Once, when he was mobbed by university students after delivering a speech, he famously let it be known that if a child of his had behaved in such a way he would have had no hesitation in putting him over his knee and spanking him. An old-style Conservative on the right wing of the party, he became one of Margaret Thatcher's most trusted lieutenants. He was her last home secretary - probably the only one to share her gut instincts on law and order - and he risked a greater degree of vilification than any of his predecessors in implementing her policies. On his watch there was rioting over the poll tax, prisoners went on the rampage at Strangeways and judicial review was ordered in the case of the Birmingham Six. Waddington's political career reached its peak in 1989 when Thatcher appointed him home secretary after Nigel Lawson's dramatic exit from the cabinet. His wife, Gilly, was once asked whether the appointment had come as a surprise to him. "Not at all," she replied. "If they made him Pope he would want to be God." Born in Burnley, Lancashire, in 1929, David Charles Waddington was the son of a solicitor, Charles, who family had made its money in cotton, and Minnie. He was educated at Sedbergh, then Hertford College, Oxford. He had a spell as a second lieutenant in the XII Royal Lancers, and recalled sailing through the Suez Canal during the first crisis.\ The canal, he wrote, "was not a pretty sight, the banks being lined by masturbating Egyptians - a very exhausting form of political protest which I have never seen repeated". In 1951 he was called to the Bar at Gray's Inn and enjoyed a moderately successful living as a barrister on the Northern Circuit. He had chaired Clitheroe Young Conservatives and been president of the Conservative Association at Oxford, and set about contesting seats for the party, but it was not until 1968 that he was elected MP for Nelson and Colne, a seat he lost to Labour's Doug Hoyle six years later. It was, he declared, "a bad day for the country and for civilisation". He was reported to have had a nervous breakdown, though he said another medical opinion was that it was encephalitis. Waddington was haunted all his life by the tragic case of Stefan Kiszko, a young civil servant charged with the murder of an 11-year old girl. Waddington represented him in 1976 in Leeds, and advised his client that his best option was to put in a plea of guilty under diminished responsibility. This he did, and his client was given life. New evidence came to light 15 years later, which proved that Kiszko had been innocent. Kiszko died, a tragic broken figure, a year after his release. Waddington returned to politics in 1979, winning Clitheroe (now Ribble Valley) in Thatcher's first election victory. He got on better with her than he had with Edward Heath, and, sensing a political soulmate, she marked him out as a key player. Two years later he was a junior minister to Norman Tebbit at the Department of Employment, where he helped to draft the legislation reforming the unions that was so central to Thatcherite policy. Waddington made no secret of his contempt for the union leaders at Congress House, making bitter, personal attacks on them in his speeches. Some of them were, he said, "nasty". In 1983, he was appointed minister of state at the Home Office, then chief whip four years later. He was highly effective and, if not the model for Francis Urguhart in House of Cards, certainly a principal source of background material. He was popular in the job, however, taking care to thank MPs personally who had stayed late to vote. As home secretary his was a brief but difficult tenure, and he found himself having to take decisions that antagonised his traditional allies. When, in 1990, he delayed sending in the riot squad after prisoners began to tear up at Strangeways and the violence escalated into chaos, he was branded "a wimp", even though he had been acting on the advice of his officials. More criticism came his way when, confronted with new evidence relating to the Birmingham Six, he had no alternative but to order a judicial review. He then had to steer the Hong Kong Bill through the Commons. The bill, allowing 225,000 of the colony's key workers and their families to be given British citizenship before its reversion to Chinese rule in 1997, raised more hackles on the party's right wing. Waddington was devastated and uncomprehending when Thatcher was cast out in 1990, and broke down in tears when it fell to him to tell her she had lost the support of her party. He went to the upper house, serving not very successfully as Leader of the Lords from 1990 to 1992, when, to his surprise, John Major offered him the governorship of Bermuda. He accepted with relish. He appreciated that the governor had a constitutional, as well as a ceremonial role, and he became one of the more hands-on incumbents. His principal achievement was the reform of Bermuda's antiquated police service, in the teeth of local criticism, bringing in two senior British policemen to fill the top posts. rather than giving them to Bermudians. Waddington fully subscribed to the British position that the island could have its independence if it was what the majority of people wanted. When, in 1995, the islanders voted in a referendum, he worked behind the scenes to ensure the issue was properly debated. That the islanders voted for the status quo was a tribute to his governorship. However, an aloof, almost regal figure, he lacked the common touch and later admitted that his personal popularity on the island had never even approached that of Basil, his beloved Norfolk terrier. Waddington married Gillian Green, daughter of the Conservative MP Alan Green, in 1958. She was a keen amateur painter and a popular and vivacious hostess at Government House. She survives him with their three sons, James - who became a barrister and, like his father, a QC - Matthew and Alistair, and two daughters, Jennifer, and Victoria, who became a drama teacher. Waddington said he regarded himself as "not a very equable person". He admitted in his later years to spending a lot of time worrying about whether he had made the most of the opportunities he had been given. He said he wanted to be remembered only as "a decent local buffer who was not all that clever, but, in his own way, tried to do his best". When the journalist John Sweeney interviewed him on Bermuda in 1994, he concluded: "Waddington was not the ogre I expected. He had been more anxious, more complicated and more human than his notices would suggest." In 2012, he published his autobiography: Dispatches from Margaret Thatcher's Last Home Secretary which revealed a more playful side to his personality. He wrote about Thatcher's habit of appointing handsome men to key posts - and about an occasion, at a rally, when he found that his hand had strayed to her knee and he wondered how to extricate himself: "Anyone who has found himself in that predicament knows that it is very much easier to get into that sort of mess than it is to get out of it." Fortunately, she did not notice. He also recalled attending a diplomatic party at the Victoria and Albert museum. No smoking signs were everywhere, but Princess Margaret emerged from behind a statue with a cigarette whose ash was an inch long. "Ah, there you are," she said to Waddington. He bowed and cupped his hand. She flicked her ash into it, and he put it in his pocket. |

Bermuda | Bermuda Administrators | OSPA

Armed Forces | Art and Culture | Articles | Biographies | Colonies | Discussion | Glossary | Home | Library | Links | Map Room | Sources and Media | Science and Technology | Search | Student Zone | Timelines | TV & Film | Wargames