|

|

|

|

Shenton Whitelegge Thomas was born in London on 10 October 1879, eldest of the six children of the Revd Thomas William Thomas, and his wife, Charlotte Susanna Whitelegge. His father's career in the Church of England took him, and his family, to parishes at Norwich and then in Cambridgeshire. Shenton Thomas was educated at St John's School, Leatherhead, from 1890 to 1898 and at Queens' College, Cambridge, from 1898 to 1901, where he held a Sedgwick exhibition and graduated in classics, with second-class honours, in 1901. He became an honorary fellow of the college in 1935. On leaving Cambridge he was a schoolmaster at Aysgarth preparatory school in Yorkshire from 1901 to 1908, with a year off to make a tour round the world in 1904.

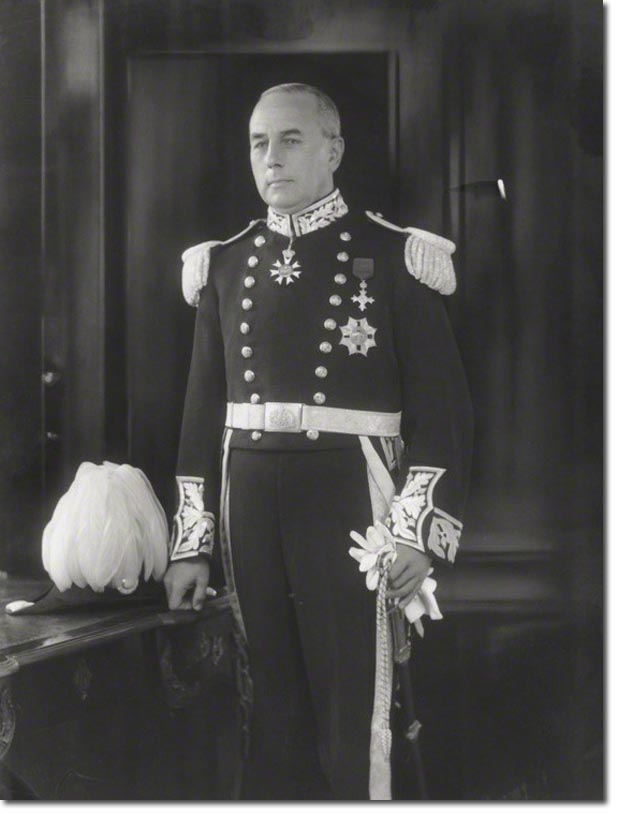

Early in 1909 Thomas arrived in the East Africa Protectorate as a recruit to the administrative service. On arrival he was posted to the secretariat in Nairobi, where he showed aptitude for the work, as he thought clearly and expressed himself well on paper. In 1912 he married Lucy Marguerite (Daisy; 1884-1978) , daughter of Lieutenant-Colonel James Alexander Laurence Montgomery, of the Indian army and later commissioner of lands in Kenya; they had one daughter. Thomas subsequently went on to similar but more senior posts in Uganda in 1918 and Nigeria in 1921. In 1927 he was appointed colonial secretary of the Gold Coast. His first governorship, in 1929, was in Nyasaland. He returned to the Gold Coast as governor in 1932, but was appointed governor of the Straits Settlements in 1934; he formally retired from that post in 1946. The rapid rise of a secretariat 'high-flyer'--Thomas never held a district post--might have attracted disparagement from less successful outstation colleagues. However, Thomas was generally popular. He and his wife were an unassuming and approachable couple, with a talent for putting at their ease the people they met. Thomas, who was a strong, thickset man, played tennis and golf, and excelled at cricket (he had played for Cambridgeshire and for the MCC). As governor of Nyasaland he once made a century, including three sixes, before breakfast, in a match begun in the early cool of the day. During his time in Singapore he occasionally played for its cricket club, and he was a regular racegoer. Thus he combined social gifts with ability, and in his time in the Gold Coast he showed firmness in dealing with political opposition. On becoming governor of the Straits Settlements and high commissioner for the Malay states in late 1934, Thomas had responsibility for the decentralized government of four settlements (including Labuan) and ten Malay states (including Brunei), and as British agent he had a vague supervisory role for British North Borneo and Sarawak. More than a decade of attempts to assimilate and integrate the federated and unfederated Malay states into a more rational structure had produced little but acrimony and a resolve by the rulers of the unfederated states to preserve their cherished semi-autonomy. In succeeding a very unpopular predecessor, Thomas had the task of bringing a steadying, emollient influence to a ramshackle regime, without seeking to alter it. In 1939 Thomas had completed his normal five-year term and, at sixty, was due to retire. However, as during the First World War, the Colonial Office invited the incumbent governor to continue in his post until the war was over. Britain provided the defence forces, each under a service chief who was answerable to superiors far away. As chairman of the local defence committee Thomas was titular head of a bickering trio who held him in little esteem. The arrival of A. Duff Cooper as UK resident minister in 1941 made the situation worse. The services required land and local labour for defence works and installations such as camps and airfields. Thomas could only pass on these demands to the state governments, since land was a subject within their exclusive control. In his post-war defence Thomas asserted that service needs were adequately met, but the response was slow and sometimes reluctant. In the later stages there were complaints that civil defence and denial of resources to the enemy by 'scorched earth' measures were inadequate. A younger and more forceful governor might have more easily energized the civilian government. However, Thomas was no Gerald Templer and in 1940-41 Malaya was not ready for leadership of that type. The disastrous defeat of 80,000 British and Commonwealth forces, supported by 30,000 local troops and civil defence workers, was due primarily to failures of strategy, training, and leadership in the armed forces, and to lack of adequate air cover and of armoured units; no civil governor could have altered the result. On 14 February 1942, with Japanese forces landed on Singapore island and the city besieged, Thomas informed London that further defence was unrealistic. General A. E. Perceval surrendered to the Japanese the next day. A Japanese attempt to humiliate Thomas by marching him through the streets of Singapore to internment was counter-productive. From Changi prison in Singapore Thomas was moved, later in 1942, to imprisonment in Taiwan, and in 1944 in Manchuria. When liberated by American forces on 25 August 1945 he weighed 9� stone (his normal weight was 12 stone). He then proceeded to Calcutta and reunion with his wife, who had been interned in Singapore throughout. When he saw the drafts of the official dispatches on the campaign by the service commanders, and later of the official history by Kirby (1957), Thomas objected to aspersions on himself and his government. These protests were ignored and his request that a report which he wrote should be published was refused. Yet a modern historian, who has examined it, concludes that 'Shenton Thomas has a case' (Allen, 214). His working papers bear witness to his determination to vindicate himself and the community which he had governed. In addition to this task he found time to be an active chairman of the council of the Royal Overseas League in 1946-9 and then of the British Empire Leprosy Relief Association in 1949-55. The flood of memoirs and historical writing on the debacle of 1941-2 generally followed the verdict of Ian Morrison, correspondent of The Times, who had interviewed Thomas in 1942, that he was 'a good solid official', who had risen to the top by hard work rather than outstanding ability, that he lacked 'colour or forcefulness', and was not the man to 'rally people in a time of crisis' (Morrison, 157). Thomas was appointed OBE in 1919, CMG in 1929, KCMG in 1931, and GCMG in 1937. He died on 15 January 1962 in London, at his home, 28 Oakwood Court, Melbury Road. Although maligned by some of his countrymen, the principles which guided Thomas's conduct in 'the greatest disaster in British military history' denied a moral victory to the conquerors. In post-war Singapore a number of highways and buildings were named after him. |

Nyasaland | Nyasaland Administrators

Armed Forces | Art and Culture | Articles | Biographies | Colonies | Discussion | Glossary | Home | Library | Links | Map Room | Sources and Media | Science and Technology | Search | Student Zone | Timelines | TV & Film | Wargames