|

Regimental History

|

|

To trace the history of the 8th Gurkha Rifles during its time as a regiment of the Indian/British army, it is helpful to refer to the unit using the name of Sylhet. The title 8th Gurkhas was given to the Sylhet Regiment in 1903, and after 4 years it was linked with the 7th Gurkhas to become the 1st and 2nd Battalions of the new 8th Gurkhas. These two regiments, the 8th and the 7th, were closely related, originating in Assam in northeast India, the 8th in 1824 and the 7th in 1835.

|

|

Raising of the Sylhet Local Battalion, 19 Feb 1824

|

|

The 16th Sylhet Local Battalion was raised on 19 Feb 1824, the date when the Governor-General appointed Captain Patrick Dudgeon to command a local battalion in the area of Sylhet on the Surma River. The title of ‘Local’ implied that it was an irregular unit. It was to consist of 10 companies of 80 men each. The establishment included 6 British officers/NCOs: a Commandant, a captain, a lieutenant, an Assistant Surgeon, a sergeant-major and a Quartermaster Sergeant. Indian officers were a Subadar-Major, 10 Subadars, 10 Jemadars, 2 Doctors and a Sircar (writer). Each company had a Drill Havildar, a Bugle-Major, a Drill Naik, a Fife Major and a Pay Havildar. The core of the regiment consisted of men drafted from 7 other local battalions, each supplying a Jemadar, a Havildar, 5 Naiks and 25 Sepoys. The men were not Gurkhas at this stage, it was not until 1828 that these mountain men began to be recruited.

|

|

War Against Burma 1825

|

|

The need for the Sylhet Battalion had been felt for many years before 1824 because of the threat from Burma. In 1823 two Burmese armies entered northeast India to claim the district around Chittagong. Three columns were organised of which one was to set off from Sylhet through Manipur. It was commanded by Brigadier-General Shuldham and consisted of 6 regiments and the 16th Sylhet Local Battalion. There was little fighting but much hard work protecting road building pioneers and keeping them supplied. The expedition was abandoned and they returned to Sylhet.

|

|

The First Gurkhas 1828

|

|

The first recruits of the Sylhet Battalion had been men from the local district but in 1828 Gurkhas were drafted in from the Nasiri and Sirmoor Battalions and recruits from Pithoragarh. There were two Gurkha Subadars and two Jemadars. From that year the Gurkha element was steadily increased but it was not until 1886 that the regiment was officially titled the 44th Gurkha Light Infantry.

|

|

Campaigning in the Khasia-Jaintia Hills 1828

|

|

In 1828 two British officers were surveying near Nongklao when they were attacked and killed by local Khasias and Garos. The Sylhet Battalion was sent out to punish the perpetrators. They fought against the tribesmen at Mamlu and secured Nongklao. Then a strong position at Mogandi was stormed on 21 May 1828, and Rajah Tirat Singh, the leader of the attack on the officers, was captured. Another local leader, the Rajah of Jaintiapur, was also captured and his lawless activities curtailed. Soon after this campaign the battalion was moved from the plains of Sylhet to the hill station of Cherrapunji. This was a welcome move for the Gurkhas.

|

|

The Khasias, 1836

|

|

The Shyhet Light Infantry was at this time commanded by Major Frederick Lister who is regarded as the ‘father of the regiment’. He was in command for more than 26 years, from 1828 to 1854 and sustained several wounds from being in the forefront of any fight. He was wounded in 1829 fighting the Khasias, and when the regiment attacked a village called Maharam in 1836 he was wounded again. The attack was successful, mainly due to the intelligence work of one sepoy, Naharsing Khattri, who disguised himself as a Khasia and was able to count the numbers of the enemy entering the Khasia stockade, and reconnoitre the best route for the regiment to take on their approach.

|

|

The Lushais and Kukis, 1844 -1849

|

|

Across the Surma River, to the south, was a range of hills inhabited by the Lushais and Kukis who terrorised their neighbours. The Cachar Valley became almost completely depopulated by their attacks. In 1844 a small expedition of the Sylhet LI under Captain W Blackwood had some success, but there was still trouble in 1845 and 1847. The instigator of the Lushai troubles was a Kuki chief named Mulah. An expedition in 1849, led by Colonel Lister attacked Mulah’s village and released 400 captured slaves. The village was destroyed and Lister’s stern measures brought the region a 12 year period of peace. Colonel Lister was again wounded in this battle. He recommended a much larger force of 3,000 men to end the problem once and for all, but the recommendation was not implemented. However, he further suggested a programme of road building, and the raising of a force of men from the Kuki tribe, which was carried out with satisfactory results.

|

|

The Indian Mutiny 1857-58

|

|

The composition of the Sylhet Light Infantry in the 1850s was half Gurkhas and half Hindustanis. All the Manipuris had been transferred to the Manipuri Regiment. The year 1857 saw the great Indian rebellion referred to as the Indian Mutiny because it involved the mutiny of Indian soldiers employed in East India Company regiments, mostly in Bengal. The existing Gurkha regiments that eventually became the 1st 2nd 3rd 6th 7th 8th and 9th Gurkha Rifles did not rebel and thus they retained their line of descent from the early 19th century whereas many of the Bengal Native Infantry units had to be disbanded.

Rebellion of the 34th NI, Nov 1857

The 34th Bengal Native Infantry were stationed at Chittagong. They had a poor reputation, having gained no battle honours and having been disbanded for mutiny in 1844. They were subsequently re-raised, and on 18 Nov 1857, inspired by events further west, they mutinied once more and began looting government buildings. Later they marched towards Sylhet to persuade the regiment to join them. Major Robert Byng at once marched his men from Cherrapungi to Petrabgarh to meet the mutineers. This was a distance of 52 miles covered in 36 hours. Reports came to him that the rebels were at Latu so they marched another 28 miles by night to confront them with a daybreak attack. On 25 Dec there was a battle on the Cachua River during which Major Byng was killed.

Individual Acts of Heroism at Cachua River, 25 Dec 1857

One mutineer shouted that the sahib of the Sylhet LI had been killed and called on the regiment to join the mutiny. Bugler Mahabulla Khan shouted back, “You have only killed our sergeant-major.” At which the adjutant, Lieutenant Sherer, ordered the bugler to sound the charge, and the rebels were dispersed. A Sylhet veteran, Subhan Khattri, who had persuaded Major Byng to allow him to join the march, shouted, “I will now show you what an old man can do!” and rushed at the enemy with kukri in one hand and tulwar in the other. He caused mayhem in the mutineers’ ranks but was killed in the process. Mahabulla Khan, the bugler, was awarded the Indian Order of Merit, along with seven others, and on 23 Nov 1879 was appointed Subadar-Major, a position he held for almost 8 years.

End of the Campaign 1858

The mutineers of the 34th were pursued, neutralised, and their loot recaptured. The regiment returned to Cherrapungi and medals were awarded. No battle honour was gained from their efforts despite the acknowledgement that the Sylhet LI, by their prompt and resolute action had probably prevented the spread of the mutiny over the whole northeast frontier.

|

|

44th Bengal Native Infantry 1861

|

|

The army in India needed drastic reorganisation after the Mutiny, mainly with the transfer from the East India Company to the Crown. The Sylhet Light Infantry was at first designated the 48th Bengal Native Infantry but within 6 months, on 29 Oct 1861, the regiment was numbered 44th. They were still light infantry but this did not feature in the title. The establishment was One Commandant, one Second-in-Command, one Adjutant, two Doing-Duty Officers, one Assistant Surgeon, 8 Subadars, 8 Jemadars, 40 Havildars, 40 Naiks, and 600 Sepoys. Additionally, they had an artillery section of one Tindal and 8 Lascars to man two 6-pounder guns which they had used since 1827. The Gurkhas made up 75 per cent while Hindustanis made up the other 25 per cent.

|

|

Jaintia Rebellion, Dec 1861 - Mar 1863

|

|

The 44th maintained an outpost at Jowai in the Jaintia Hills, garrisoned by a platoon commanded by Jemadar Kharag Sing Rana. In 1861 they came under attack from a large force of Jaintias led by U Kiang Nangbah and were besieged for 9 days. A message was sent to Lieutenant-Colonel Richardson who immediately relieved the outpost. But the rebellion, which was a protest against the imposition of taxes, gathered strength and Khasias joined in too. In 1862 there were many assaults on peaceful Jaintia stockades. The situation was serious enough for the authorities to send a column in December 1862, containing the 44th, two companies of the 43rd, one battery, 4 battalions of Native Infantry and one of Rattray’s Sikhs (at that time this regiment were Military Police). One incident took place in this conflict that became a legend in those parts. A sepoy named Karbir Lama was attacked by a famous Khasia warrior near a river. Hearing the commotion, another sepoy, Banka Sing, ran to help Karbir. As he approached he was knocked down by another Khasia but Banka recovered and shot his assailant. He then hurled himself at the famous warrior who was much larger than himself, and dragged him into the river where he held him under the water until he was dead. The rebel leader, U Kiang Nangbah was caught and hanged, but operations lasted until March 1863 when the rebellion was regarded as over.

|

|

Bhutan War 1864-66

|

|

Duar Field Force 1864

A series of raids by the Bhutanese brought about a plan to invade and annex the region. Four columns were organised and the 44th were in the Right Centre Column which headed for Sidli, while the 43rd Assam Light Infantry were in the Right Column which was directed towards Dewangiri. The Right Centre column captured Sidli and went on towards Bishensing, 42 miles further on through dense jungle. When the annexation was thought to be complete the Duar Field Force was broken up. The Bhutanese, however, did not regard themselves as annexed, and counter-attacked those forts that had been captured. The Daranga Pass was now under their control so that the field force were cut off from their base. The fort at Dewangiri came under the most serious assault. This was manned by the 43rd and some gunners and sappers who were forced to retreat. The guns were abandoned and the survivors reached the base in a very demoralised state. The CO was relieved of his command.

The Recapture of Dewangiri, 3 April 1865

Two brigades were formed and given the task of imposing British authority on the Bhutanese. The 44th and 43rd were allotted to the Right Brigade under the command of Brigadier-General Harry Tombs VC which was tasked with the recapture of Dewangiri. Setting off on 24 Mar 1865, Tombs deceived the enemy by sending a detachment to another pass further west so that the Daranga Pass was secured without loss of a single man. The siege of Dewangiri was not as arduous as expected and the recapture was accomplished on 3 April. Sepoy Bakhat Sing Rai of the 44th was the first man into the stockade and captured a Bhutanese standard. Brigadier Tombs handed over command of the column to Colonel W Richardson of the 44th on 23 April. Nine months later, in Feb 1866 Richardson led a successful sortie from Dewangiri to defeat a Bhutanese force that was in possession of the guns originally captured in 1864. These were handed back and the Bhutan War was brought to a close. The casualties from this conflict were mainly men who had fallen sick from the unhealthy climate of the Terai. So heavy were the losses from fever that both the 44th and the 43rd were ordered to Gauhati to recuperate. These regiments came out of Bhutan in April 1865 and the 44th returned for the final battle at Dewangiri in Feb 1866. They eventually returned to Cherrapunji in March 1866.

|

|

Moving to Shillong 1867

|

|

The regiment had been based at Cherrapunji for more than 30 years but in 1867 were moved to Shillong, a healthy and very popular hill station. After they had settled in, Captain Kalu Thapa remarked that there wasn’t a single rat there.

|

|

Expedition against the Lushais 1871-72

|

|

Following repeated Lushai attacks on civilians, the authorities prepared two columns to enter their territory in a punitive expedition. The 44th Sylhet Battalion was part of the Cashar Column together with a Mountain Battery, the 22nd Bengal NI and the 42nd Assam Light Infantry. They were commanded by Brigadier-General G Bourchier. They set off from Cachar on 21 Nov 1871 and advanced to Tipia Kukh. A wing of the 44th had a sharp skirmish in a pass leading to Champhai. This pass was held by Lalbura, a Lushai chief, but they were badly defeated. The village was destroyed by fire and there was less resistance from the Lushais after that. The other column, the Chittagong Column achieved fame because they secured the release of Mary Winchester, a six-year-old girl, along with other captives. Peace was concluded by April 1872 and the 44th returned to Shillong. It had been an arduous campaign and the regiment had lost 43 men. Brigadier Bourchier praised the officers and men under his command:

‘From the beginning of November, when the troops were first put in motion, to the present time, every man has been employed on hard work, cheerfully performed, often under most trying circumstances of heat and frost; always bivouacking on the mountain-side in rude huts of grass and leaves, officers and men sharing the same accommodation; marching day by day over precipitous mountains, rising at one time to 6,000 feet, having made a road fit for elephants a distance of 103 miles. The spirit of the troops never flagged, and when they met the enemy they drove them from their stockades and strongholds until finally, they were glad to sue for peace.’

Bakhat Sing Rai who distinguished himself in Bhutan was now a naik and his 3rd Class Order of Merit was up-graded to 2nd Class. Jemadar Shamlal Khattri was also awarded the 3rd Class Order of Merit. The Indian Medal with clasp for Lushai was awarded to all who took part.

|

|

The Daphla Hills 1873-74

|

|

The Daphlas were another troublesome group that gave cause for concern in the region. In 1872 there was a serious incident in which another Daphla colony, having settled at Amtola in British territory, was attacked by fellow tribesmen. They carried away more than 40 captives. In April 1873 a detachment of 100 men of the 43rd Assam LI had been praised for their good work in the Daphla Hills and they were frequently in action there up until 1878. The Daphla country is very mountainous and covered with thick jungle. The local people regarded a day’s journey of 8 miles a strenuous effort. Leeches could not be avoided so that the whole Daphla experience was the stuff of nightmares. In Nov 1873 a force under the command of Major Cory marched into the Daphla Hills. This consisted of detachments from the three Assam battalions, the 42nd 43rd and 44th. Their objective was limited to a blockade, and to ensure this, they were accompanied by the Political Officer. The expedition was ineffectual so another incursion was organised a year later in November 1874, this time under Brigadier-General Stafford and made up of men from the same battalions. There was little fighting and the Daphlas gave assurances of peace.

|

|

Massacre at Ninu, 2 Feb 1875

|

|

In February 1875 a survey party under Captain Baggaley went into the Naga Hills, escorted by a detachment of around 150 of the 44th Sylhet LI. The Deputy Commissioner, Lieutenant William Holcombe, aged 27, accompanied the party, confident that he would be able to persuade the Nagas to live in peaceful co-existence with their neighbours and under the benign influence of the British government. They reached Ninu village on 1 Feb and stayed overnight so that negotiations could be conducted the next morning. On 2 Feb a large crowd of hundreds of Nagas were permitted to enter the village. In a rash act of bonhomie, Holcombe took a rifle off one of the soldiers to give to a Naga leader. The soldier’s protests fell on deaf ears, but the Deputy Commissioner’s foolish demonstration of trust backfired with catastrophic consequences. The Naga leader raised the weapon in the air, signalling a general uprising. Holcombe was set upon and hacked to death. The soldiers of the 44th defended themselves as well as they could but had to make a fighting withdrawal. Ten soldiers were killed and nine wounded in the initial scramble. But there was desperate fighting as they were pursued to the plains so that the final casualty figure was 80 killed and 50 wounded. Only 20 men reached Shillong unwounded. Amongst the dead were the Jemadar commanding the detachment, and Bakhat Sing Rai, by then a Havildar, who had distinguished himself at Dewangiri in 1865, and against the Lushais in 1872.

Colonel Nuttall’s Reprisal, Feb 1875

When news of the massacre reached Colonel Nuttall of the 44th, on 16 Feb he paraded every available man and marched immediately to the Naga Hills. On 23 Feb, he was joined by men of the 42nd and 43rd regiments. The expedition was extremely difficult as rivers had to be crossed that were swollen by heavy rain. But they penetrated the region and wreaked revenge on the Nagas. Villages were destroyed and weapons and plunder retrieved. The Indian Order of Merit was awarded to four men of the 44th.

|

|

Naga Campaign 1879 - 80

|

|

Siege of Kohima Oct 1879

As trouble flared up on the North West Frontier, the Assam Battalions had to deal with a Naga uprising on the North East Frontier. In October 1879 several hundred Nagas attacked a party of the 42nd Assam LI at Konoma. The survivors made their way back to the stockade at Kohima, but this came under attack. Forty men of the 43rd Assam LI reinforced this position but the siege lasted two weeks until Kohima was relieved by a force of 2,000 Manipuris under Colonel Johnston.

Konoma 22 Nov 1879

The 44th had been sent west to take part in the Second Afghan War. Having only got as far as Goalundo they were recalled and joined a force that consisted of the three Assam battalions and a part of the 34th NI, all under the command of Brigadier-General Nation. In November the villages of Sachima and Sephima were captured but the main Naga fortress was at Konoma. The 44th were equipped with Bubble and Squeak, their 7-pounder mountain guns. These, however, proved ineffective against the walls and stockades so Colonel Nuttall, CO of the battalion decided to storm the place. The outer wall was breached easily but the inner fortification was a 12 foot stockade on top of a stone-faced scarp. Lieutenant Ridgeway led two assaults on the stockade during which he was severely wounded. He reached the gateway and attempted to pull away planks to create a breach in the enemy defences. For this he was awarded the Victoria Cross, gazetted on 11 May 1880.

It was getting dark so there was a lull in the fighting. The Gurkhas held their ground and planned to resume the attack the next day. But the detachments of the 43rd and 44th that had been posted to prevent the Nagas escaping to the south were withdrawn at nightfall so when dawn broke it was found that they enemy had got away. The Nagas headed for the 9,000 ft high Chaka mountains and fighting continued in the form of guerrilla warfare. Detachments were posted to various parts to protect convoys and patrol the vicinity. The Nagas finally surrendered on 27 Mar 1880.

The Hardship of the Naga Campaign

The men suffered greatly from fever, dysentery and ‘Naga sores’ throughout their time in this hill campaign. Things were made harder from the lack of transport. Because the Indian Government was preoccupied with the war in Afghanistan, little attention was paid to the needs of the Assam Battalions. Things were beginning to improve just as the campaign was coming to a close, but up until then the men suffered discomfort, and operations were seriously hindered. Following the cessation of hostilities an official report acknowledged that time and money would have been saved if the Gurkhas ‘had been always equipped to take the field at short notice.’ However, the end of the war did not mean that the Nagas adopted a peaceful coexistence with the British. A detachment of the 44th remained at Kohima until 1884 and there were several incursions into the hills to mete out punishment.

|

|

|

|

| Badges

|

|

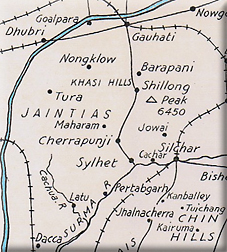

| Map of Northeast India

|

| Colonels

|

| 1824 - 1947

|

| Commanding Officers

|

| 1824 - 1947

|

| Soldiers

|

| 1824 - 1947

|

| Uniforms

|

| 1824 - 1947

|

| Band

|

| 1824 - 1947

|

| Battle Honours

|

|

BURMA 1885-87

World War One

LA BASSEE 1914

FESTUBERT 1914-15

GIVENCHY 1914

NEUVE CHAPELLE

AUBERS

FRANCE AND FLANDERS 1914-15

EGYPT 1915-16

MEGIDDO

SHARON

PALESTINE 1918

TIGRIS 1916

KUT-AL-AMARA 1917

BAGHDAD

MESOPOTAMIA 1916-17

AFGHANISTAN 1919

Second World War

IRAQ 1941

NORTH AFRICA 1940-43

GOTHIC LINE

CORIANO

SANTARCANGELO

GAIANA CROSSING

POINT 551

IMPHAL

TAMU ROAD

BISHENPUR

KANGLATONGBI

MANDALAY

MYINMU BRIDGEHEAD

SINGHU

SHANDATGYI

SITTANG 1945

BURMA 1942-45

|

|

| Titles

|

| 1824 | 16th Sylhet Local Battalion |

| 1826 | 11th Sylhet Local (Light) Infantry Battalion |

| 1861 | 48th Regiment of Bengal Native Infantry |

| 1861 | 44th Regiment of Bengal Native Infantry |

| 1864 | 44th (Sylhet) Regiment of Bengal Native (Light) Infantry |

| 1885 | 44th(Sylhet) of Bengal (Light) Infantry |

| 1886 | 44th Regiment Gurkha (Light) Infantry |

| 1889 | 44th (Gurkha) Regiment of Bengal (Light) Infantry |

| 1891 | 44th Gurkha (Rifle) Regiment of Bengal Infantry |

| 1901 | 44th Gurkha Rifles |

| 1903 | 8th Gurkha Rifles |

|

| Successor Units

|

| 1907 | 1st Battalion 8th Gurkha Rifles |

| 1947 | On Partition: To India |

|

|

Suggested Reading

|

History of the 8th Gurkha Rifles 1824 - 1949

by H J Huxford (Gale & Polden 1952)

Sons of John Company, The Indian and Pakistan Armies 1903 - 1991

by John Gaylor (Spellmount 1992)

|

Armed Forces | Art and Culture | Articles | Biographies | Colonies | Discussion | Glossary | Home | Library | Links | Map Room | Sources and Media | Science and Technology | Search | Student Zone | Timelines | TV & Film | Wargames

|