|

Background to Conflict

|

|

The reasons for the British invasion and occupation of Afghanistan in the late 1830s are many and varied. They mainly revolve around what one of the 'victims' of the event referred to as 'the Great Game'. This was the name given by Arthur Conolly to denote the shadow boxing between Russia and Britain for influence in Central Asia for much of the 19th Century. Relations between Russia and Britain were strained in the 1830s as the British feared the expansionist and strong armed tactics of Tsar Nicholas I who came to the throne in 1825. He sought a policy that expanded Russian influence southwards and eastwards. This was bringing Russian influence towards Britain's own 'Jewel in the Crown' India. India was still ruled by the East India Company, although the British government had constrained much of the company's freedom to act by this time and was ultimately guiding its policy on the wider international scene. The British were particularly concerned at Russian influence in Persia. They had heard reports that the Russians were helping the Shah of Persia beseige Herat on the western side of Afghanistan. If successful in taking this city, Russian influence would advance along the route that they would take if they were to invade India at any point in the future. But British alarm bells really began to ring when a rumour circulated that a Russian had arrived at the court of Dost Mohammed in Kabul. If this was true, then it was believed that Russian influence might extend to the borders of India itself. Steeped in classical education, most British decision makers knew the invasion route of India taken by Alexander the Great and assumed that the Russians would soon have the capability to make a similar incursion.

Efforts to contain the spreading Russian influence were vigorously pursued by the British. Their man on the spot in Kabul was Alexander Burnes. He went by the nickname of 'Bokhara Burnes' due to his remarkable exploits at exploring great swathes of Central Asia the decade previously. His accounts of the strange and foreign lands were a publishing sensation in the 1830s and he was a household name and one trusted to get to the bottom of what was occurring in the mysterious palaces of Central Asia. Another British officer took to the fore in Herat at almost the same time. His name was Lieutenant Eldred Pottinger and he was a 26 year old subaltern who had been posing as an Islamic holy man on a routine 'Great Game' reconnaisance mission in the region. Coincidentally he was in Herat when the Shah of Persia's army arrived to besiege the city. Pottinger made himself known to Yar Mahammad Khan, the wazir and commander of the forces under Shah Kamran, ruler of Herat, and offered his services for the city's defence. The Persians were being advised by a Russian Officer, Simonich, but they had not reckoned on the vigorous activities of the young Pottinger whose expertise did much to save the city from falling. The Foriegn Minister, Palmerston, had already determined to stand up to the Russians and despatched a fleet to the Persian Gulf which disgorged troops on the island of Kharg. The effect of this was immediate on the Shah of Persia. Frustrated by his inability to enter Herat and now concerned that the British might threaten to invade his Persia from the western side convinced him to call off the siege of Herat and withdraw his troops. It appeared that British gunboat diplomacy had succeeded in keeping Russian influence at bay. However, there was still one more fly in the ointment for the British. They had been concerned about the actions of the mysterious Captain Vitkevich who had arrived at the court of Dost Mohammed in Kabul.

Burnes had known Dost Mohammed from his previous days travelling and exploring through Central Asia. He was very impressed by Dost Mohammed and felt that he was an unusually strong leader in a region that had only known division. Burnes' intention was to keep Dost Mohammed in place and develop and foster friendly relations with his stable government. Dost Mohammed was very cordial to Burnes and wished to reciprocate the friendly approaches by Burnes. Strategically though, the British authorities in India had already invested their goodwill to a bitter rival of Dost Mohammed's; Ranjit Singh. Ranjit Singh was the elderly ruler of the Sikh Kingdom of Punjab. The Sikhs and Afghans clashed regularly between the heights of the Himalayas and the fertile valleys approaching them. Relations between the rivals reached a nadir when Ranjit Singh's army captured the Peshawar Valley from the Afghans. Dost Mohammed asked the British for help in having it returned to the Afghans, but the British had already declared support for Ranjit Singh. His Sikh Empire was the most formidable army on the borders of British India. It was hoped that Ranjit Singh's Sikh state would provide a powerful buffer between themselves and a Russian backed Persia. The British Governor-General of India, Lord Auckland did not wish to offend Ranjit Singh and so decided that Britain would side with Ranjit Singh in his dispute with the Afghan ruler. Dost Mohammed felt that he had no alternative and so welcomed the young Captain Vitkevich into his court to investigate what the Russians might bring to the diplomatic table. For Lord Auckland, the mere presence of a Russian in Kabul was an affront. He felt that Dost Mohammed had to be replaced before the Russians could embed their influence on the borders with India.

The British and their Sikh allies did have a replacement in mind. His name was Shah Shujah and he had been the ruler of Afghanistan from 1803 to 1809 before being overthrown in a palace coup. Since then, he had sought the help and support of both the Sikhs and the British to regain his position.

It had fallen to Burnes to warn Dost Mohammed not to entertain any negotiations with the Russians. Dost Mohammed was furious at being told who he could and could not talk to in his own country and made a point of publicly inviting Captain Vitkevich to his court and showing him hospitality. Burnes had merely been the messenger of British policy but it was clear that his mission to Kabul had failed and so he withdrew to India to report to his superiors.

On the face of it, Vitkevich had much to report to his own superiors back in St. Petersburg. His mission had gone far better than anyone in Russia had hoped possible. Unfortunately for him, events elsewhere in Central Asia had turned against the Russians. So that by the time of his return to the Russian capital, the Persian withdrawal from Herat was complete and the extent of Russian aid to the Persians had been revealed by the British. Palmerston had demanded the recall of both Vitkevich and Simonich on the grounds that they were destabilising Central Asia. The Russians were dangerously isolated in Europe at this point in time and did not wish to provoke the pre-eminent power into anything that might look like war. The Russian government sought scape-goats and claimed that both men had exceeded their orders and instructions and they were to be recalled and punished as a result. For Vitkevich the shame of being publicly blamed for policy failures in Central Asia was too much and he took out a revolver and shot himself in the head after his discussion with the Foreign Minister. It appeared that the Russians would not follow up on their in-roads into Dost Mohammed's court. And yet, the wheels of action had already started turning back in India.

Lord Auckland had made up his mind that Dost Mohammed must go. He was backed up in this assessment by William Macnaghten, Secretary to the Secret and Political Department in Calcutta. Macnaghten argued that Dost Mohammed could be overthrown relatively cheaply and easily by the use of troops loyal to Shah Shujah and with soldiers from Ranjit Singh. On October 1st, Auckland issued the 'Simla Manifesto' that publicly announced his intention to replace Dost Mohammed with Shah Shujah. Diplomatically, Auckland had committed himself to the overthrow of the Afghan ruler and events in St Petersburg were not going to change his stated course of action. For Ranjit Singh, there was no need to offer his own troops for the mission. He was fully aware that he had much to gain whilst sitting back and allowing the British and Shah Shujah do his work for him. His long time rival would be removed, his claim on Peshawar Valley would be respected and upheld and an ally would be installed on the throne on his border. He prevaricated on the supply of troops but gave permission for the British and Shah Shujah to march through his territories or travel up the River Indus in order to reach Dost Mohammed's territory. He prevailed upon the British to launch their attack from the southern Bolan Pass rather than the more direct Khyber Pass as he wished for Dost Mohammed's position to be weakened throughout the length of his territories and particularly in the Kandahar region. The plans had been set, troops were being raised and the invasion was set to begin. The press back in England was as Russophobic as ever and clamoured for a show of force. It had got to the state where an invasion of Afghanistan was the easier course of action than to announce its cancellation. Still, it was hoped that the invasion would be swift and that the Afghans would welcome the return of their old King and that the British could quickly withdraw once they had placed the compliant Shah Shujah on the throne.

|

|

The Army of the Indus

|

|

A force of 9,500 Crown and Company troops assembled with a further 6,000 followers of Shah Shujah at Ferozepore in the Punjab. The initial preparations did not go fully according to plan when a British line of elephants collided with Ranjit Singh's during a ceremonial parade. Less than majestically, the elderly Ranjit Singh tumbled from his elephant to an inglorious landing flat on his face in front of two British 9 pounder guns. Still, the military show of force was convincing as the army moved up the mountain valleys of the Bolan Pass towards Quetta, Kandahar with the intention of then moving on Kabul itself. The force was augmented by a truly huge collection of camp followers; servants, families and various hangers-on. It was said that the commanding officer, required 260 camels just to carry his own personal equipment. Everything needed to be carried, but the sheer size of the invasion force put a strain on the supplies of the force itself and the land it was passing through.

The advance through the Bolan Pass was laborious. Burnes had managed to buy safe passage from the Baluchi chiefs whose domain they were passing through. However, despite assurances of safety there were attacks on stragglers and supply columns although the main force advanced with little disruption. The biggest problem facing the advancing British was in attaining fresh food and water. The previous harvest had been a poor one and the large collection of people passing through the area put a strain on the resources of the land and local people. To make matters worse, a second British force was following shortly behind. It had been despatched by sea to the mouth of the river Indus and it had marched up the river with the intention of uniting with the first force at Quetta. Privation was making morale a problem as soldiers went hungry and thirsty. It was only through Burnes' ability to release government-provided funds and purchase 10,000 sheep from the Baluchis, at a seller's price it must be said, that disaster was averted.

Whilst the invasion was struggling towards Quetta diplomatic representations were being made by the British Indian Government to neighbouring chiefs and leaders. Colonel Charles Stoddart was despatched to the neighbouring Khanate of Bokhara to assure the Emir that he had nothing to fear from the British advance into Afghanistan. Unfortunately for Stoddart, his mission was to go tragically wrong when he caused offence to the Emir through a series of etiquette blunders. Besides, the Emir of Bokhara was more concerned at the reports of a Russian army heading towards Khiva and did not wish to offend them unnecessarily at this point by agreeing to discuss any issue with the British. Stoddart was kept in a dreadful condition of imprisonment for years. He was to be joined by his would-be rescuer Arthur Conolly. Both were later executed but only after suffering years of privation and cruelty.

Back at Quetta, the two forces amalgamated under the command of Sir John Keane. He now had 21,000 soldiers and many more camp followers for the march towards the western stronghold of Kandahar. It was feared that Kandahar could be fortified and turn into a major siege. However, intelligence received by the British indicated that the city had been evacuated by its defenders and that it was wide open to the British forces. It was at this point that Macnaghten decided that it would be best for Shah Shujah to 'liberate' the city with his own forces and he duly marched into Kandahar at the head of his own troops. A curious crowd welcomed Shah Shujah and Macnaghten felt that his scheme had been vindicated by the ease of the operation and the welcome received. He decided to put on a military parade and durbar to commemorate the return of Shah Shujah. Thousands of soldiers marched passed Shah Shujah in full regalia. A 101 gun salute was thundered out for all to hear. It was a success in every aspect but one. Almost no Afghans bothered to turn up to witness the spectacle. It should have been clear to the British that Shah Shujah did not have the popular support that Macnaghten and he himself had claimed. Disappointed, the British continued their advance towards Ghazni which lay on the road to Kabul.

Ghazni was a formidable fortress that lay on the road between Kandahar and Kabul. It was a significant town in its own right whose walls were thought to be impregnable. The advancing British were surprised at just how impressive a structure it was with 60 foot high walls of an impressive thickness. Due to the supply problems, Keane had left his siege guns back in Kandahar. The British only had light field pieces that were never going to penetrate the thick walls of the defences. Fortunately for the British, they had a resourceful native intelligence officer called Mohan Lal accompanying them. This very well connected individual had established contact with an old colleague within the city. This friend informed Mohan Lal that all the gates had been bricked up on the inside except one; the Kabul Gate.

Armed with this information, it was decided that engineers would use satchel charges to blow open the gates and assault the defenders from this northerly gate. The officer who volunteered for the operation was Henry Durand of the Bengal Engineers. The attack was conducted at night to help the young engineer and fellow sappers to sneak into position. A diversionary attack was launched at the opposite end of the fortress to draw attention away from the Kabul Gate. Henry Durand and his sappers laid the charges against the gate but it took three attempts for Durand to get the fuse alight. Eventually it spluttered into life and he was able to dive into cover seconds before the charges exploded. The gates had been breached and the nearby storming party made for the hole under the command of Colonel William Dennie. Disaster was narrowly averted when a bugler called the retreat signal by mistake instead of the advance one, but the order was quickly countermanded and the attack resumed. The Afghans fought back ferociously but had not yet fought a well-trained European army and they were unused to the discipline and organisation of their foe. Some 500 defenders were killed by the storming party inside the fortress and even more had been cut down by the cavalry waiting outside the walls to hunt down escapees. The British lost only 17 dead with a further 165 wounded. The Union Jack was raised over the ramparts and the road to Kabul was now open.

Dost Mohammed's authority began to collapse quickly after this setback. At about the same time, he lost another outpost at Ali Masjid to another smaller British column that had begun to advance to Kabul through the Khyber Pass. Support for Dost Mohammed evaporated and he himself fled northwards rather than defend his capital. Just seven days later, Keane's army stood at the walls of Kabul and found the city abandoned of defenders. Once more, Shah Shujah led the way into his conquered city but there were no crowds to welcome him. He was met by a stoney silence and a wall of indifference. It was not a good omen.

|

|

The New 'Pro-British' Regime of Shah Shujah

|

|

Shah Shujah, despite his age, looked the part of a Central Asian ruler. He was an attractive looking elder statesman who dressed in bejewelled robes. He was childishly delighted to be back in his old capital, although he said that everything seemed so much smaller than he remembered! But few were fooled as to where the real power behind the throne lay; The British diplomats and political officers along with the officers of the remaining British garrison. Macnaghten and Burnes were the main decision makers alongside the newly appointed garrison commander Major General Abraham Roberts. Keane and his army of the Indus duly left when it appeared that all was calm. An infantry division, a cavarly regiment and an artillery battery were all that remained to uphold the rule of the pro-British administration.

The manner of Keane's withdrawal should have hinted that the remaining British forces were not going to have an easy time of it. Despite payments to tribes to desist attacking British supply and communications lines, ambushes and picking off of stragglers were happening with regularity. Keane's withdrawal was very much a fighting one with punitive raids and pacifying villages and heights along the main roads and by-ways linking the major cities of Afghanistan. A significant deviation had to be made to subdue the tribes at Khelat. A substantial force had to be left in Kandahar to subdue the tribes and to maintain peace in the western section of Afghanistan under General William Nott. Two more garrisons were set up in Ghazni and Jellalabad. The rest of Keane's forces returned to their respective presidencies and the rule of Shah Shujah was thought to have been installed relatively straightforwardly.

The British diplomats and officers set out to occupy themselves in their new posting. They built a racetrack, skated on frozen ponds, acted in amateur productions and set up cricket matches. They loved to watch Afghan wrestling and cock-fights - especially if wagers could be laid. In short, they tried to enjoy themselves in this far flung corner of the empire. Dinner parties were held by the senior diplomats and officers on a regular basis. The Afghans watched the new conquerors with curiosity and bemusement at first, but were perturbed with instances of drunken soldiers or examples of Afghan women entertaining British personnel. There were even some instances of the British garrison marrying local women much to the consternation of traditional Afghans. Other soldiers sent for their families. The arrival of wives and children helped turn the atmosphere into that of a more familiar garrison posting.

The British felt so secure in their position that they moved their garrison out of Kabul itself into a cantonment to the east of the city. This was standard practice in India where large garrisons set up outside of peaceful cities. They had no defences as such, just a large parade ground on flat land with lines of tents or huts. In this case, the Kabul River separated the cantonment from the city and it was overlooked, menacingly, by hills and ridges.

There remained the issue of Dost Mohammed. He had fled north to the capricious mercies of the Emir of Bokhara. Nasrullah Khan had originally imprisoned Dost Mohammed unsure of how events on his border would unfold. When he realised that the British might be in the region to stay, he released Dost Mohammed who rode southwards with a party of Uzbegs. Reports of the return of Dost Mohammed perturbed the British political officers but on November 4th 1840 they had a pleasant and most unexpected surprise. Whilst out riding, Macnaghten and his personal secretary Captain George Lawrence were approached by two Afghan horsemen. After some confirmation of identities, Dost Mohammed revealed himself to Macnaghten and surrendered his sword to the 'effective' leader of Afghanistan. Macnaghten was delighted with this seeming vindication of all that he had claimed back in Simla the year before. The Shah Shujah was on the throne and the person he had dispossessed had willingly surrendered and was escorted back to a comfortable and dignified imprisonment in British India. Authorities in India were so happy with this turn of events that they started planning for the complete withdrawal of all British forces from Afghanistan in a staged series of draw-downs. By this time, they were more concerned at the costs of occupation and it seemed as if the British could transfer this burden and responsibility back to Shah Shujah and his soldiers and administration.

|

|

The Slide into Oblivion

|

|

Shah Shujah was not proving to be the model leader that Macnaghten had claimed for him, despite his regal appearance. He was vindictive and surrounded himself with yes-men and advisers who were more concerned at enriching themselves than in helping the people they ruled over. He did not have the allegiance or respect that Dost Mohammed had cultivated from surrounding tribal leaders. Shah Shujah was utterly dependent on the British for his position, and everyone knew it.

British soldiers were increasingly being jostled and insulted in the streets and bazaars of Kabul. Afghans blamed the foreigners for the rise in prices as the well paid servants of the Crown drove prices ever higher for the locals. Afghan women began to steer clear of the foreigners. One poor officer, Lieutenant Loveday, was found murdered and chained to a camel pannier in the hills south of Khelat. Soldiers could no longer travel unattended but were advised to stay in groups.

The more professional of the soldiers were concerned at the poor siting of the cantonment and its inability to be adequately defended from the heights surrounding it. Reports from Kandahar and the surrounding countryside warned that the mullahs were preaching of the need to expel the foreigners from Afghanistan. Macnaghten would hear nothing of these complaints and insisted that all was going according to plan. He had been promoted to the Governorship of Bombay as a reward for his success in Afghanistan and did not want to rock the boat until he had departed for his post. Most of the professional British officers were starting to have serious suspicions that all was not as it should be including the Commander-in-Chief Major-General Roberts. He was so disillusioned with the rose-tinted view of Macnaghten that he requested a transfer and resigned his position as Commander-in-Chief.

The bean counters back in India and in Britain were concerned at the ongoing costs and demanded that Macnaghten make savings on the venture. They asked that non-essential forces be sent back to India. Much of Nott's forces around Kandahar were earmarked for return and prepared to leave the country. Even more worryingly, Macnaghten was forced to reduce the payments to those tribes who controlled the vital passes in and out of Afghanistan. They had honoured British freedom of movement in return for substantial payments. As these were now being cut, there was no guarantee that the lines of communication would any longer be clear for the garrison in Kabul.

Roberts' replacement was the venerable and almost decrepit Major General William Elphinstone. He had last seen active service at Waterloo and had been looking for a nice, quiet backwater posting to see himself out until his retirement. He did not speak a word of Hinustani but was an old friend of Auckland's and was seen as someone who would not disrupt or question the current policy. His fellow officers could barely conceal their dismay at such a doddering replacement in such a delicate situation. He was impeccably mannered but could barely walk for gout and other infirmities. It would fall to this man to preside over one of the severest calamities ever to befall the British Army.

Events started to spiral out of control for the British on the 1st November 1841. Mohan Lal had warned Burnes that his contacts were telling him that an attempt on Burnes' life was going to be made that very night. Burnes was confident that the attempt would not amount to anything significant. He reinforced his sepoy guard but otherwise refused to move from his house to the safety of the cantonment or the Bala Hissar. Besides, he thought, the main force of British troops was only two miles distance from his home.

Meanwhile, rumours had been spread around the bazaar that Burnes kept the soldiers' pay and the gold for maintaining British power in the region in the house next door to his. A small crowd appeared that evening outside of his house. It steadily grew, partially out of curiosity, but also responding to the opportunity to get hold of some of the treasure. Burnes' own personal morals had identified him in the eyes of many Afghans of being particularly suspect. It was known that he hosted parties where alcohol ran freely and women were invited, even Afghan women! The combination of righteous rage inspired from the mullahs coalesced easily with the potential for personal enrichment. And all along the crowd grew bigger and became more ominous.

Burnes refused to give the order to open fire on the protesters. He thought that events might spiral out of control if he did give the order, besides, the nearby British garrison or Shah Shujah's troops must surely respond soon to the kerfuffle playing out on the streets around his home. Just in case, he despatched a runner to the cantonment to beg immediate assistance. Unbeknownst to Burnes, indecision had already paralysed the main decision makers. Macnaghten's Secretary, Captain George Lawrence, had immediately proposed sending a significant force to disperse the Afghans before events escalated any further. Elphinstone and Macnaghten, however, prevaricated. Elphinstone had fallen off his horse earlier that day and had not fully recovered. The elderly general lacked the will or energy to initiate a decisive course of action. Macnaghten was paralysed by his ambition. He did not want to use troops to disperse a mob just before he left for his coveted governorship. He did not wish for any blemishes on his record sheet, and certainly not at this late stage.

The compromise course of action was to send troops to the Bala Hissar and coordinate a response with Shah Shujah. When these troops arrived, they discovered that Shah Shujah had already sent troops and he declined the offers of any additional help or support from the British insisting that his own troops were quite sufficient for the task at hand.

Meanwhile, events at Burnes' residence had escalated still further. The crowd had started pelting the house with stones and someone had set light to the stables. Burnes was trying to talk the crowd into dispersing. He had alongside him his brother and Major Broadfoot in charge of the sepoy guard. Suddenly a shot rang out and Major Broadfoot fell to the ground. He was carried inside but was found to be dead.

The sepoys were now given permission to fire, but it was too late. The crowd had been emboldened to see a British officer fall before their eyes. Mohan Lal watched events with dismay from a nearby rooftop. His warning had been ignored and now he was watching the unfolding horror but was powerless to intervene. He watched Charles Burnes try to fight his way through the mob only to be hacked to pieces as he attempted to do so. Alexander Burnes appears to have been lured into native disguise by someone only to be betrayed as he emerged into the street. He was then hacked to death. Shah Shujah's forces had easily been repulsed by the huge crowd which now descended on the residence and the treasure with abandon. Some thirty sepoys, servants and colleagues of Burnes were also butchered unceremoniously within half an hour's march of 4,500 British soldiers. Once they ransacked their intended targets, the mob moved off to loot shops, burn buildings and cause mayhem on a citywide basis.

|

|

Uprising

|

|

Macnaghten and Elphinstone had not yet ordered a punitive column to restore law and order. The lack of British troops on the streets only emboldened the mob yet further. The British were struck with paralysis and Shah Shujah's forces had been ignomiously forced from the streets back to the relative safety of the Bala Hissar. They had suffered over 200 casualties in their ill-fated attempt to rescue Burnes.

The following days saw reports come in to speak of a much wider outbreak of violence towards Shah Shujah and the British. In Charikar, a British Gurkha regiment has been all but wiped out. General Sale had been marching from Kabul to Jellalabad for winter quartering but his force had been savagely attacked in the passes and he barely made it through to the fortress. The tribes controlling the passes no longer felt compelled to honour British freedom of movement due to the cut in their payments instigated by Macnaghten. In addition to this there were reports of patrols being attacked on the roads to and from Kabul and even as far west as Kandahar. One of General Nott's columns had disappeared without a trace. It was clear that Afghanistan was sliding into a full blown uprising. The only thing it lacked was a clear leader, or so it seemed.

During November there came reports that a son of Dost Mohammed had crossed into Afghanistan at the head of an army of 6,000. His name was Akbar Khan and he had the credibility and the grievances to lead the Afghans and expel the British and the usurper Shah Shujah from Kabul and Afghanistan for good.

The British situation was looking precarious across the country but it wasn't until the 23rd of November that the Afghans felt strong and confident enough to attack the cantonment iself. Many British soldiers had long despaired at the impossibility of defending such a base. This was confirmed when the Afghans moved two guns above the camp and started bombarding it. Elphinstone's indecisiveness finally came to an end and he ordered an attack on the position. Initially, the attack went well and cleared the two guns from the heights. However, the brigadier in charge then thought it necessary to clear the corresponding villages to which the gunners and attendants had fled towards. Advancing with just a single artillery piece, the task seemed like a formality for such a well drilled army. However, the guns overheated from firing grapeshot at the village and a large force of Afghan horsemen suddenly appeared. The British responded by forming into two squares with some cavalry between reading itself for a counterattack. The tactics were perfectly suitable to a European battlefield but the Afghans were unwilling to follow doctrine. Instead, they used their longer range jezails to deadly effect and were content to pick off soldiers from afar. The British were unable to respond as the gun was still overheated and their own muskets couldn't reach their targets. Suddenly, a force of Afghans appeared from an unseen gully close to the squares and launched themselves at the British squares which promptly broke and ran. The brigadier bravely rallied his troops and with the help of the recovered gun beat the Afghans off with heavy losses. Long range Jezail fire continued to take its toll and was to be followed by a second force to break from another gully and force the British back a second time. This was the final snapping of the force morale and they ran all the way back to the cantonment abandoning equipment and wounded as they did so. Being so intermingled with advancing Afghans, the British in the cantonment could give little aid to their fleeing comrades. They were fortunate that the Afghans did not feel confident enough to continue their advance into the camp itself. It was an ignominious defeat that seemed to confirm the hopelessness of their exposed position. It appeared to some that their only route to survival was through negotiation.

The following day appeared to show just such an opportunity. Akbar Khan had arrived in Kabul with his 6,000 fighters to added to the 25,000 Afghans already in arms there. From this position of strength he agreed to enter negotiations, mindful of the fact that the British still held his own father as hostage in India. Elphinstone was easily persuaded to give Macnaghten permission to negotiate due to the precarious state of his forces and with the arrival of winter making a swift deal even more of a necessity. Indeed, they had just received confirmation that there would be no relieving force coming to the aid of those in Kabul due to heavy snowfall in the passes. The Kabul garrison was alone and would have to fend for itself.

Akbar's terms were harsh. He demanded that Shah Shujah be turned over to his custody, the British were to hand over their arms and leave immediately for India and that Dost Mohammed be released and that various British hostages be kept until this last term was fulfilled. Macnaghten refused outright the demands and both sides returned to a state of preparedness expecting the fighting to resume.

Macnaghten felt bold enough to propose his own terms in the belief that the Afghan tribal leadership was not as united as it at first appeared. Mohan Lal had heard that many of the tribal leaders were anxious at the prospect of the return of Dost Mohammed. Some actively preferred the weak and ineffective Shah Shujah as it gave them more control and license over their own territories. Macnaghten proposed that the British would withdraw to the frontier (fully armed) and bring Shah Shujah back to India with them. Akbar would agree to accompany them to the border and four British hostages would remain in Kabul to see that he was released. It was further proposed that Dost Mohammed would be released on their safe arrival in India and that Afghanistan vowed not to enter into an alliance with any other foreign power in the future. Meanwhile, Mohan Lal was given the task of fomenting turmoil and strife by trying to divide the Afghan tribal leaders through money and promises. It appeared as if efforts were beginning to bring some success when a sudden invitation was made to Macnaghten by Akbar himself.

The new proposals were startling. Shah Shujah could remain on the throne but Akbar would become his Vizier. The British would stay in Kabul over winter and return to India in the spring. Those responsible for the death of Burnes would be handed over and Akbar would receive a subsidy from the British to help him with his rivals. Macnaghten felt that Akbar had been forced to compromise due to weaknesses in his own powerbase. He therefore agreed to meet with Akbar in secrecy to finalise the arrangements. What Macnaghten did not realise was that Akbar had indeed been worried about the division created in the various tribal leaders but he was going to solve his problems by the removal of Macnaghten and the decapitation of the leadership of the British in Kabul. At the secret rendezvous Macnaghten was seized and murdered by Akbar himself. His three colleagues were stripped and seized. One was killed as he fell from a galloping horse and the others were imprisoned in a dark, dank cell. Akbar had demonstrated to everybody who was calling the shots. He had reunited the tribal leaders and had fatally weakened the leadership capability of the British.

Once more, the Afghans braced themselves for a swift British response to their dastardly deed. Once more, the resolve of Elphinstone floundered. Instead of showing a steely determination to fend for themselves, they procrastinated. They were more concerned at the weather conditions and the desperate shortage of supplies. The wounded Eldred Pottinger had taken over from the murdered Macnaghten and he urged Elphinstone to make a bold strike and occupy the eminently more defendable Bala Hissar. Elphinstone over-ruled Pottinger with the support of his senior officers. They just wanted to return home with the least risk possible and that road seem to lie with a fresh round of negotiations.

Any respect that the Afghans may still have harboured towards the British in Kabul had evaporated by this stage. Elphinstone's lack of direction bred contempt in Akbar and the tribal leadership. Akbar dictated severe terms. The soldiers were to leave Afghanistan forthwith, notwithstanding the falling snow. They must surrender their artillery, what was left of their gold and must hand over more hostages, including wives and children. The terms were harsh but Pottinger was instructed to accept them by Elphinstone. He did modify some of the demands for women and children to remain behind and even managed to argue keeping six of their artillery pieces. They were also told that they would be escorted to the border and that food and fuel would be supplied to them to enable them to evacuate Kabul. But in principle, the British were going to have to make an arduous journey at the height of winter but only with the acquiescence of the Afghans. Mohan Lal warned the British that they were doomed unless they themselves had sons of tribal leaders as hostages in order to ensure the terms were respected. Elphinstone and the senior commanders were so keen to leave that they did not bother trying to renegotiate and so accepted the good faith offer made by Akbar.

|

|

The Retreat

|

|

On January 6th, 1842 Elphinstone's army began its march out of the cantonment towards the nearest occupied fortress at Jellalabad. They abandoned Shah Shujah to his fate in the Bala Hissar. The advance guard was the 44th Regiment of Foot with some cavalry as support. The army was swelled massively by camp followers who did not wish to remain at the tender mercies of Afghan hospitality. The promised escort and supplies failed to materialise as promised. Pottinger urged Elphinstone once more to change his plans and head for the relative safety of the Bala Hissar where they would be reinforced with Shah Shujah's contingent. Elphinstone would hear nothing of it and ordered the force to continue on regardless. Some 16,000 trudged out of camp on a bitterly cold January morning.

The attacks on the column started almost immediately. Barely had they left the cantonment before the deadly jezails began taking their toll on stragglers and isolated parties. The onslaught only worsened as the Afghans gained in confidence as the British left the relative security of their base. Afghan horsemen drove off baggage animals, unarmed camp-followers were mercilessly preyed upon. As the poor unfortunate camp-followers sought sanctuary amongst the soldiers, they only helped disorganise the formations and make effective defence of the column even more difficult. The whole sorry column only made five miles that first day, but the snow was already blood-red from the slaughter. Stragglers staggered into the makeshift camp until late into the night. Needless to say, the freezing cold temperatures plummeted yet further during the night and nearly all the tents had been lost in the day's pillaging. What shelter could be provided was offered to the wives and children. Many of the men who had been forced to sleep in the snow froze to death during the night. The first 24 hours had been horrific enough, but there was still another week of travelling to go!

Sniping continued all the next day and more attacks were made on the precious few remaining artillery pieces. By the end of the day, they only had 3 pieces left. At midday, Akbar arrived claiming that he would guide them and provide for their safe passage through the passes ahead. He even chastised them for leaving before they were supposed to the day before. He said that he was not in control of all the tribes in the area and requested that Elphinstone stop his column whilst he negotiated with the next tribe on the route through the passes. Unbelievably, Elphinstone agreed to these demands too. He even agreed to hand over three further hostages to show good faith. The British had barely covered 10 miles and now faced another night in the open.

Akbar's promised escort did not show up the next morning, so the British set off through one of the narrowest parts of the passes. Worse was to follow as it became clear that not only had Akbar failed to negotiate a route through tribal lands, he had almost certainly warned the Afghans to be ready to ambush and attack the British. The sniping and attacks were more fearsome than ever. Some 3,000 died this day alone including many women and children.

Despite the obvious signs of treachery, Elphinstone entrusted Akbar a further time the following day. Akbar offered to 'protect' the wives and children of British officers along with some of the wounded officers. Some nineteen further hostages were handed over but it did not buy any relief from the onslaught.

The ambushes and sniping continued throughout the day. By nightfall, there were only 750 soldiers left alive. Some two-thirds of the camp followers were dead too.

Two further days of slaughter whittled the force down yet further. The remaining force was barely able to fend for itself when Elphinstone himself was seized by Akbar. He had gone to discuss yet further terms with Akbar when he was told that he could not return to his troops and had to remain as a prisoner. Elphinstone was at least able to smuggle a message to his second in command to tell them to move off as fast as possible. Finally, the British regained some initiative and they could see with their own eyes yet another piece of treachery that Akbar had been planning for them. A narrow part of the pass had been barricaded in order to bottle the advancing British up under yet another torrent of fire. The surprise British advance had caught the Afghans unawares as they had not expected them to reach the barricade yet. When the Afghans realised their error they rushed towards the barricade and tried to hold the British up. The fighting was severe but the darkness saved the lives of many. Two small groups of soldiers got through, one group mounted and one on foot. The riders tried to put some distance between themselves and the Afghans. There were only fifteen cavalrymen remaining, but their horses gave them some advantage of speed.

The second group of 65 infantry would go down in history due to their last stand at Gundamak. Quickly surrounded by Afghans, they realised that they were not going to make it to the safety of Jellalabad. When the Afghans offered to take them into custody and escort them to safety in return for handing over their weapons, the British had lost all trust and point blank refused the request. The British only had twenty muskets and two rounds each by this time, but they formed into a square and prepared to fight. When the bullets ran out, they used their swords and bayonets. Only four men were captured, the rest died where they fought.

The cavalry group reached a village, Futtehabad, where they were offered food which they gladly accepted. Unbeknownst to the men, they were about to be betrayed. A secret signal was given to Afghans waiting in the surrounding hills to swarm into the village. Only five of the cavalry men managed to get out of the village. Of those, all but one were killed in the ensuing chase. That last man's name was Dr Brydon and he would become the only survivor from the column who would make it alive to the fortress at Jellalabad. Even he was lucky to make it the final fifteen miles to the fort. He was attacked again and again in that last dash to safety. The fort at Jellalabad was itself nervous of being attacked and were expecting to see hordes of Afghans appear on the horizon at any moment. So the lookout was very surprised to see a solitary mounted European heading towards them. The scene was made famous by Lady Butler in her 'Remnants of an Army' painting. The fortress kept on looking for survivors and burnt large fires to guide other stragglers towards Jellalabad, but no other stragglers survived to make the journey. Of the 16,000 who had started the journey, just one made it to safety.

|

|

The Plight of the Isolated Garrisons

|

|

Far more robust leadership had been shown in the west of the country by General William Nott. He had been based in Kandahar with a small garrison and given the task of keeping the west of Afghanistan and the southern passes open as communication routes for the British. He almost became a victim of his own success when the Indian Office ordered him to draw down his troops and return them to India as Afghanistan appeared pacified. Complete disaster in the west was averted when news of a shocking incident spurred Nott into recalling the retreating troops before they had gone beyond his reach. The event which shocked him into decisive action was the wiping out of a British force under the command of Captain Woodburn. These had been travelling on a routine mission travelling from Kandahar to Kabul when swarms of Afghans descended upon them. They sought refuge in Syadabad but were betrayed and massacred. Only two sepoys lived to tell the tale of the outrage. Unlike Elphinstone, Nott realised the danger of his position. He sent another force towards Kabul but it could not get further than Ghazni. Nott realised that trouble was brewing and recalled as many of his garrisons and patrols back to Kandahar as he could. Ghazni, however, could not be evacuated in time. Colonel Palmer had been forced to withdraw from the city into the Citadel when some of the local townspeople betrayed the existence of tunnels to the attacking Afghans. Khelat-i-Ghilzai was another garrison that could not be evacuated due to the weather and its isolation, it did however receive a fresh infusion of troops under Colonel Maclaren who had been sent to try and evacuate it.

Nott's condition deteriorated when one of Shah Shujah's own sons defected from Kandahar and united with the surrounding Afghan tribesmen. Undeterred by these events, Nott took the initiative and sent a force out to disperse the growing band of troublemakers congregating around the city. He had bought some time. It wasn't until the 31st of August that Nott had heard of the murder of Macnaghten at Kabul and understood that there was a full blown country-wide rebellion underway. Three weeks later, he received the startling order from Elphinstone, his commanding officer, to retreat to India with all of his forces. He decided to ignore this order believing that the order had been written under duress. He evaded the order by saying that he would await confirmation from Calcutta before proceeding with the evacuation. General Sale in Jellalabad had received similar instructions but, wisely, he had ignored them also.

The remaining British forces in Afghanistan were still not out of danger yet. Rumours that the garrison at Kabul had been wiped out had reached the defenders of Ghazni and Kandahar and of course had been made all to aware to the garrison at Jellalabad that had received the solitary survivor Dr Brydon. The massacre had also emboldened the Afghans who now turned their attention to these other garrisons. The first to fall was Ghazni which had been commanded by Colonel Thomas Palmer. He had felt compelled to accept terms to accept safe passage out of the citadel to return to Peshawar. This was primarily due to a shortage of supplies and water. Almost immediately on leaving the relative safety of the citadel, they were set upon by hostile Afghans. Desperate hand to hand combat ensued from house to house as the sepoys and officers sought desperately to escape. All the sepoys were eventually killed and some of the British officers were taken hostage. Colonel Palmer was tortured into revealing the whereabouts of British money and gold which the attackers assumed had been buried and hidden by the British. Eventually the remaining 9 British officers were taken to Kabul to be united with the earlier Kabul garrison hostages.

Meanwhile, in Kandahar, a force of 12,000 Afghans descended upon the city. Nott was far more aggressive than Palmer or Elphinstone had been with regards to the local population. He turfed them all out of the city so that they did not take up valuable resources nor would they be able to betray them, as some had Palmer in Ghazni. Nott set off to disperse the Afghans gathering, which he duly accomplished, but had not realised that more Afghans were heading towards the city and it was only saved thanks to the heroic defence by Major Lane, on 11 March 1842.

Nott had been hoping to receive reinforcements by way of Quetta under General England. These were initially repulsed from Haikalzai and had had to return to Quetta. Nott's situation seemed hopeless especially as he was running out of food, supply and money to pay his troops. He ordered General England to once more attempt to break through to Kandahar but this time through the Khojak Pass. Nott sent a force of his own soldiers to the northern end of the pass to await and help England's force to pass through and into Kandahar bringing much needed supplies, ammunition and money.

March would see Khelat-i-Ghilzie under sustained attack from the Afghans. The attackers dug trenches encircling the place and lay down sustained fire from protected positions. On 21 May a major assault with scaling ladders was mounted but beaten off in a fierce battle which effectively ended the siege. They were delighted to receive a fresh force sent from General Nott with orders to evacuate them back to Kandahar.

Nott was aware of yet another force that was massing at the River Arghandab. Aktur Khan, the Durrani chief, had assembled 3,000 men and joined the force under Safter Jang and Atta Muhammad on the right bank of the Arghandab. Nott moved out with a part of his force, leaving General England with a smaller force to protect Kandahar itself. On 29 May Nott attacked and defeated the Afghans, and drove them in confusion and with great loss across the Arghandab River. He had cleared Western Afghanistan. With the exception of the loss of Ghazni, he had been remarkably successful in his military encounters with the Afghans and illustrated what could be achieved in Afghanistan with more vigorous and determined leadership.

Sale had been equally proactive in his defence of Jellalabad. Ever since his force's traumatic journey from Kabul to the fort, he had been aware of the vulnerability of his position. He set about increasing the fortifications and defences available to him. The fort came under repeated attacks but in March Akbar Khan himself turned up at the head of the army that had wiped out Elphinstone's force. He set up a siege around the fort and waited for the garrison to capitulate. Sale was hoping for a relieving force to arrive from Peshawar under General George Pollock. However a rumour circulated claiming, falsely, that Pollock's force had been wiped out. Rather than await for a final Afghan onslaught, Sale decided to take the initiative and ordered his troops to sally out of the gates and engage the surrounding Afghans. A 12 hour battle ensued which saw the Afghans put to flight. Akbar Khan had been defeated and the garrison could replenish its supplies from the surrounding countryside. One week later, Pollock's force arrived from Peshawar. The British position had been stabilised on both flanks of Afghanistan. The choice was what to do next?

|

|

The Army of Retribution

|

|

There had been a change of government back in Britain and the incoming Tory government under Peel wished to wash its hands of the entire sorry affair and leave the blame to lie squarely with Melbourne's outgoing Whig government. The governor general of India, Auckland was replaced by Lord Ellenborough who had been given strict instructions to get Britain out of the Afghanistan imbroglio. However, he decided that British prestige in the sub-continent demanded one final demonstration of Britain's military and political capabilities. He proposed sending an army of retribution to gain one final victory over the Afghans. The last thing he wanted was a newly emboldened Afghan state on his doorstep that might decide to invade Peshawar or other North West Frontier provinces. He wanted to blunt their ambitions and reveal Britain's true military capabilities. Besides, there were still numerous British hostages in Afghanistan and he wanted to negotiate their release from a position of strength, or even to liberate them outright. He had no intention of remaining in Afghanistan once he had achieved his aims but he felt that he had to make this final grand gesture or British prestige would be fatally undermined not just in Afghanistan but throughout India.

By the time Ellenborough had arrived in his post, Sale, Pollock and Nott had all turned the tide in their respective missions and spheres of operation. Internal politics had also taken a more complicated road after Akbar lured Shah Shujah out of the security of the Bala Hissar and murdered him. Far from strengthening Abkar's position, his rival tribal leaders grew worried about his growing power and prestige. An internal power struggle began and Afghanistan appeared to be sliding back into its normal chaotic state. Ellenborough considered abandoning his plans for an army of retribution but the generals on the ground implored him to allow them to seek vengeance on behalf of their fallen comrades and hostages and restore prestige before evacuating the country. Ellenborough conceded to their request in a roundabout way saying that they could withdraw 'via Kabul' which effectively meant giving them the green light to make a final show of force on the ground. Pollock and Nott started something of a race to Kabul to take the honour of being the first force back into the city. Pollock's force had a far more manageable distance of 100 miles compared to Nott's 300 miles - although the passes and heights were far more daunting for Pollock's force than for Nott's. Both forces made a dash for the Afghan capital.

Pollock's force soon saw for themselves the devastation that befell Elphinstone's force as they came across mile upon mile of frozen corpses and abandonend paraphernalia. Ellenborough's requests to show restraint in the treatment of Afghans would be sorely tested by the sights that Pollock's men saw for themselves; mutilated men and women, genitalia stuffed into the mouths of their fallen comrades, breasts hacked off of women and infants frozen to death. British soldiers responded by wiping out villages and farms that they came across. The barbarities of war had escalated to sub-human levels and little pity or mercy was shown to any Afghans who happened to fall in the line of Pollock's march.

Pollock's force arrived in Kabul only hours before Nott's force was able to do so. They found a city that had all but been deserted as the residents and defenders were rightfully fearful of the manner of British retribution. Akbar himself had long deserted the city, fleeing northwards. British forces were able to enter the formidable Bala Hissar without firing a shot. As they raised the Union Jack once more in the city, they found the evidence of the British debacle, from the abandoned cantonment to the burnt out walls of Burnes' residence. What they did not find, were the 90 odd hostages that were being held by Akbar.

A negotiating party under Captain Shakespear was organised and sent to locate Akbar and the hostages. As his small force was riding northwards he came across a remarkable scene just outside of Bamaian. He found the former British hostages advancing towards him. In the confusion of the evacuation of the hostages, Pottinger and Mohand Lal had managed to bribe their guards with promises of money and safe conduct passes into not taking them to Turkmenistan as Akbar had ordered. Instead, they had taken control of a small fort in Bamaian, flown the Union Jack, established friendly relations with the local tribesmen and paid their former guards to become their protectors. When they had heard of Shakespear's mission to free them, they had come out to intercept and greet him. In a highly emotional scene, many of the hostages broke down in tears and thanksgiving. They were now safe and could return home. Shakespear learned that Elphinstone had died during his time in captivity. This was almost certainly a blessing in disguise as it saved him from the disgrace of having to explain his actions to a court of enquiry.

Back in Kabul, Pollock was considering how best to demonstrate Britain's displeasure before withdrawing from the country once and for all. He considered blowing up the mighty Bala Hissar but was begged not to do so by those who had remained loyal to Shah Shujah as they would then be defenceless and at the mercy of Akbar should he return in the future. Instead Pollock decided to destroy Kabul's bazaar where Macnaghten's body had been left hanging for all to see some nine months earlier. It took the engineers two days to destroy the massive structure with explosives. The city was plundered and ransacked by the British who were in an unforgiving mood. They had been given orders not to harm anyone, but in the confusion, discipline disappeared and many innocent Afghans found themselves on the receiving end of British indignation.

The British then withdrew and made the journey through the Khyber Passes for a final time. There was little cheer despite their recent successes as they were constantly reminded of the horrors that befell their comrades as they rode along the detritus of Elphinstone's destroyed force yet again. Lord Ellenborough ensured that the returning soldiers were greeted with celebrations and much fanfare, but few were fooled by the extent and degree of the calamity that had befallen the British in their 3 year long venture into Afghanistan. Pollock's was a pyrrhic victory in an ultimately disastrous sequence of events.

|

|

End Game

|

|

The political situation in Afghanistan turned full circle when the British released Dost Mohammed unconditionally from their captivity. He returned to Afghanistan and retook his position as leader. He deposed Shah Shujah's son who had claimed the throne on the death of his own father. It is even rumoured that Dost Mohammed had his own son, Akbar, murdered in 1847. Perhaps he was fearful at the ruthless streak that his son had shown and worried that he might turn on him in the future. It was not unusual for sons to murder their fathers in leadership struggles in Central Asia.

Ironically, Dost Mohammed went on to prove that he could be a trustworthy neighbour to the British. He maintained a semblance of order, in a country that experienced little of any order. He did not make the mistake of inviting the Russians to Kabul again and kept a neutral stance in geo-political affairs. Vitally, he did not take advantage of the Indian Mutiny when it occurred in 1857. In fact, the North West Frontier was so stable that the British felt confident enough to draw down their forces on the frontier to fight against the mutineers. Dost Mohammed had shown that he was only interested in ruling Afghanistan and that he could be trusted. If only the British had realised this earlier!

|

|

|

|

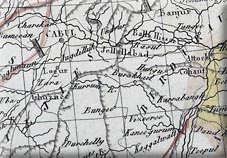

| Maps of First Afghan War

|

| Significant Individuals

|

British and Allies

Opponents

|

| British and Imperial forces

|

|

Army of the Indus

Sir John Keane

British Forces

4th (The Queen's Own) Regiment of (Light) Dragoons

16th (The Queen's) Regiment of (Light) Dragoons (Lancers)

2nd (The Queen's Royal) Regiment of Foot

13th (1st Somersetshire) Regiment (Light Infantry)

17th (The Leicestershire) Regiment of Foot

Indian Forces

2nd Bengal Light Cavalry

3rd Bengal Light Cavalry

3rd Skinner's Horse

31st Lancers

34th Poona Horse

Shah Shujah's Regiment

1st Bengal Fusiliers

16th Bengal Native Infantry

48th Bengal Native Infantry

31st Bengal Native Infantry

42nd Bengal Native Infantry

43rd Bengal Native Infantry

2nd Bengal Native Infantry

27th Bengal Native Infantry

19th Bombay Infantry

2nd Company, Bengal Sappers and Miners

3rd Company, Bengal Sappers and Miners

1st Company, Bombay Sappers and Miners

|

|

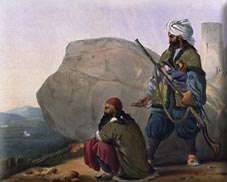

| Images of First Afghan War

|

| Timeline

|

| September 20th 1837

|

Alexander Burnes arrives in Kabul

|

| December 24th 1837

|

Vitkevich arrives in Kabul

|

| January 20th 1838

|

Lord Auckland writes to Dost Mohammed and tells him Britain will back Ranjit Singh

|

| June 19th 1838

|

British Troops land at Kharg Island in Persian Gulf to put pressure on Persia to withdraw from Herat

|

| June 1838

|

Secret Deal between Ranjit Singh and Britain

|

| September 9th 1838

|

Persians withdraw from Siege of Herat

|

| October 1st 1838

|

Simla Manifesto

|

| November 1838

|

Army of Indus Starts Invasion of Afghanistan

|

| 25th April 1839

|

Shah Shujah and British enter Kandahar

|

| 20th June 1839

|

Ranjit Singh dies

|

| 22nd - 26th July

|

Wade attacks Ali Masjid

|

| 23rd July 1839

|

Battle of Ghazni

|

| 6th August 1839

|

Shah Shujah enters Kabul

|

| 13th November 1839

|

Capture of Kalat

|

| May - September 1840

|

Siege of Kahan

|

| 4th November 1840

|

Dost Mohammed Surrenders to British

|

| April 1841

|

Elphinstone takes over as CinC

|

| 9th October 1841

|

General Sale's March from Kabul to Jallalabad

|

| 1st November 1841

|

Burnes is attacked and killed

|

| ? November 1841

|

Akbar Khan returns to Afghanistan at head of Uzbeg Army

|

| 23rd November 1841

|

Cantonment attacked from heights

|

| 23rd December 1841

|

Akbar Khan murders William Macnaghten

|

| 6th January 1842

|

Retreat begins

|

| 12th January 1842

|

Nott clears Kandahar

|

| 13th January 1842

|

Dr Brydon arrives at Jellalabad

|

| March, 1842

|

Akhbar Khan Besieges Jellalabad

|

| 9th - 21st March, 1842

|

Siege of Khelat-i-Ghilzai

|

| 11th March, 1842

|

Battle of Kandahar

|

| 15th March, 1842

|

Fall of Ghazni

|

| 5th April 1842

|

Shah Shujah murdered

|

| 6th April 1842

|

Sale's break out from Jellalabad

|

| April 1842

|

Pollock's forces unites with Sale's force

|

| 29th May 1842

|

Nott attacks at Arghandab

|

| 9th August 1842

|

Nott leaves Kandahar for Kabul

|

| 9th August 1842

|

England leaves Kandahar for Quetta

|

| 20th August 1842

|

Army of Retribution departs from Jallalabad towards Kabul

|

| 17th September 1842

|

Pollock Arrives in Kabul and so does Nott

|

| 12th October 1842

|

Pollock Withdraws from Kabul

|

| 12th November 1842

|

Pollock's forces arrive in Peshawar

|

|

|

Accounts

|

The Afghan Wars

by Archibald Forbes

The Military Operations at Cabul

by Lt Vincent Eyre

The History of the War in Afghanistan Part 1

by Sir John Kaye

The History of the War in Afghanistan Part 2

by Sir John Kaye

Cabool : a personal narrative of a journey to, and residence in that city, in the years 1836, 7, and 8

by Sir Alexander Burnes

Narrative of the Campaign of the Army of the Indus Volume 1

by Richard Kennedy

Narrative of the Campaign of the Army of the Indus Volume 2

by Richard Kennedy

History of the War in Affghanistan: from its commencement to its close

Ed by Charles Nash

Fifty Years of John Company

From the Letters of

General Sir John Low of Clatto, Fife

1822-1858

By Ursula Low

|

|

Suggested Reading

|

Frontier And Overseas Expeditions From India: Volume Iii Baluchistan And First Afghan War

by Intelligence Branch Amy Headquarters India

|

Ackermann Military Prints Uniforms Of The British And Indian Armies 1840-1855

by William Y. Carman

|

The North-West Frontier -

British India and Afghanistan

1839-1947

by Lt. William Barr

|

The North-West Frontier -

British India and Afghanistan

1839-1947

by Michael Barthorp

(Blandford Press 1982)

|

The Extermination of a British Army: The Retreat from Kabul

by Terence Blackburn |

The British War in Afghanistan: The Dreadful Retreat from Kabul in 1842

by Tim Coates

|

Military Operations At Cabul: Which ended in the Retreat and Destruction of the British Army in January 1842

by Vincent Eyre

|

The Afghan Wars 1839-42 and 1878-80

by Archibald Forbes

(Darf 1987)

|

Fortescue's History Of The British Army: Volume XII Maps

by J. W. Fortescue

|

The Anglo-Afghan Wars (Essential Histories (Osprey Publishing))

by Gregory Fremont-Barnes |

Sale's Brigade In Afghanistan With An Account Of The Seisure And Defence Of Jellalabad

by G. Gleig

|

Narrative Of The Late Victorious Campaign In Afghanistan, Under General Pollock

by Lieutenant Greenwood

|

With the Ghurkas in Afghanistan: the Defence of Char-Ee-Kar During the First Afghan War, 1841---Char-Ee-Kar and Service There With the 4th Goorkha... the Goorkha War & Types of Ghoorkha Soldiers

John Haughton and Eden Vansittart

|

The Great Game

by Peter Hopkirk

|

Campaign Of The Indus In A Series Of Letters From An Officer Of The Bombay Division

by Holdsworth, T.W.E.

|

A Narrative of the March and Operations of the Army of the Indus in the Expedition into Afghanistan in the Years 1838-1839

by W. Hough

|

Retreat and Retribution in Afghanistan, 1842: Two Journals of the First Afghan War

by Margaret Kekewich

|

Raj - The Making and Unmaking of British India

(Little,

Brown & Co 1997)

The Rise and Fall of the British Empire

(1994)

by Lawrence James

|

Fidelity and Honour: The Indian Army from the 17th to the 21st

Century

by S.L. Menenzes

|

Retreat from Kabul: The Catastrophic British Defeat in Afghanistan, 1842

by Patrick Macrory

|

With the Somersets in Afghanistan: the Recollections of an Officer of H. M. 40th Regiment During the First Afghan War 1838-42

by John Martin Bladen Neill

|

The First Afghan War 1838-1842

by J. A. Norris

|

Rough Notes Of The Campaign In Sinde And Afghanistan In 1838-9 (Ghuznee Campaign 1839)

by James Outram

|

The Ten-rupee Jezail: Figures in the First Afghan War, 1838-42

by George Pottinger and Patrick Macrory

|

The Dark Defile

by Diana Preston

|

The Savage Frontier

by D. S Richards

|

Journal Of The Disasters In Afghanistan 1841-42

by Lady Florentia Sale

|

Lady Sale's Afghanistan: an Indomitable Victorian Lady's Account of the Retreat from Kabul During the First Afghan War

by Lady Florentia Sale |

An Officer in the First Afghan War: Narrative of Services in Beloochistan & Afghanistan, With the Army of the Indus, and Beyond

by Lewis Robert Stacy

|

The Crimson Snow

by Jules Stewart

|

With the Cavalry to Afghanistan: The Experiences of a Trooper of H. M. 4th Light Dragoons During the First Afghan War

by William Taylor |

North-West Frontier 1837 to 1947

by Wilkinson-Latham, Robert

(Osprey 1977)

|

Beyond the Khyber Pass: The Road to British Disaster in the First Afghan War

John H. Waller

|

|