| Intial Contacts | |

Despite its relative proximity, British formal involvement in the Middle East came relatively late within the context of its imperial expansion, especially when compared to further flung imperial interests in the Caribbean, Asia and the Pacific. It was not really until the Nineteenth Century that any formal colonies were established in the region at all, and even then they were mostly islands and ports. With the exception of Egypt (which was something of a complicated and special case), it was not until after the First World War that significant parts of the region were coloured pink on any maps of Empire. This is not to say that Britain had no interest in the Middle East, rather it was largely because the Middle East that Britain tended to come into contact with already had long established polities with existing power structures, a powerful and unified religion and a long, ongoing and complex history with Europe. Indeed, European feelings towards the world of Islam had long been a complex mix of respect, awe and fear. In the Middle Ages Islam had even come so far as to threaten the very existence of Christian Europe. The Ottoman Empire had firmly established itself in the South East of Europe and presented a considerable military and political power in the Eastern Mediterranean and North Africa. The English of the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries largely associated the Ottoman Empire with the Middle East in its entirety and had little conception of the further Empires and Khanates beyond the considerable Ottoman lands.

As far as European trade had been concerned, it was the Venetians who worked with the Ottoman Empire to provide the last maritime leg of the profitable Silk Route and help bring Asia's exotic goods to market in Europe. In fact, Portugal's own maritime thrust around Africa was largely designed to avoid the Ottoman Empire and bypass this powerful middleman and also avoid the equally powerful Venetian Empire in its heyday. Rounding the Cape of Good Hope provided new trading possibilities that meant that the Middle East could be avoided in entirety by ships willing to make the long voyage around Africa. Spanish attempts to discover a route via sailing West were also largely to avoid the Ottoman and Venetian stranglehold also. The fact that the Americas lay in between Europe and Asia provided a complex distraction for the Spaniards for many years although Spanish antipathy to Ottoman power in the Mediterranean continued to rage throughout the Sixteenth Century, culminating in the battle of Lepanto in 1571. Whilst these Portuguese and Spanish maritime advances were occurring, England had to content itself largely to nibbling at the crumbs of the new opportunities by sending out her own mariners to follow and emulate the Iberian seamen.

| | The Levant Company | |

Using the principle that my enemy's enemy is my friend, Elizabethan England investigated the possibilities of trading with the Ottoman Turks. As already mentioned, the Ottomans had long been involved in a war with the Spanish throughout the Mediterranean. The Protestant English felt far more threatened by Catholic Spain than by Muslim Turkey and so decided to send diplomatic feelers out to investigate the opportunity of trade and perhaps a more far reaching Entente with the Ottoman Court. Queen Elizabeth also appreciated that her diplomatic overtures would offend not only the Spanish but the Pope also. Sir Edward Osborne lobbied the English Court for a monopoly of trade with the Ottomans. He was given permission to send his chief factor, William Harborne, to Constantinople in 1578 to negotiate terms of access to the silk route goods arriving in Ottoman lands. It took until 1580 to reach an accommodation with the Sultan Murad III, but the key to unlocking any intransigence was the fact England was willing to trade munitions for the spices and exotic goods of the Orient. In fact, the Pope had specifically issued an edict against any Christian supplying weapons or gunpowder to the Turks on pain of ex-communication and in solidarity with the Spanish Crown. The complex agreement was nearly fatally undermined from the very start though, when an English ship, the Bark Roe, plundered some Greek ships under the Sultan's protection blissfully unaware of the new trading arrangements being made. William Harborne was actually imprisoned by an indignant Sultan and was only released when Elizabeth sent a heartfelt apology and agreed to send an Ambassador to Constantinople to avoid any such misunderstandings in the future. Indeed, William Harborne would later return to Constantinople as that Ambassador from 1583 to 1588.

To take advantage of these new opportunities the Turkey Company was formed in 1581 which was later merged with the Venice Company in 1592 to create the Levant Company. Thanks to the active Ambassadorship of William Harborne, a whole network of trading consulates were set up throughout the Middle East and North Africa. One active trader, John Newbery, even set up trading posts stretching from Aleppo to India. The English were keen to remove at least some of the middlemen to purchase carpets, silk, pepper, spices, wines and delicacies and transport them by ship back through the Mediterranean to England. Of all the ambitious overseas trading aspirations of Tudor England such as the Muscovy or Virginia Companies, the Levant Company would prove the most profitable and enduring of all. England had access to the products of the Orient for the first time. She still had to pay local customs and taxes to the Ottomans, but her ships did not have to take the long and perilous voyage around Africa - a route which which was still jealously guarded by the Portuguese.

John Newbery's trading connections through the Middle East and on to India gave him privileged access to key suppliers of spices, precious gems and Oriental goods. Queen Elizabeth furnished him with a letter of introduction to the Mughal leader Akbar the Great and substantially funded a 1583 expedition led by him and including one of the founders of the East India Company, Ralph Fitch, directly to India itself. The journey passed through Baghdad, Basra and went on to Hormuz whilst intending to cross the Indian Ocean to India itself. At Hormuz, Newbery went about setting up a factory to extend his trading network ever closer to the Orient. However, only ten days into his enterprise at the straits he was surprised to find that he and his entire expedition were to be arrested by the Portuguese and taken to Goa. The Portuguese had been made aware of the Englishmen's presence by Venetian traders who themselves were keen to hold on to their middleman position in the trading of goods between Asia and Europe. Besides, the Portuguese were still smarting from the circumnavigation of the world by Francis Drake which had fired upon Portuguese ships in addition to acquiring spices in the Moluccas Islands. Fortunately for the English traders at Goa an intercession by two Jesuit priests (one of whom was English) and a Dutch trader who vouched for them meant that they were released after three weeks of imprisonment relatively unharmed. Ralph Fitch left Goa in 1584 and headed to Akbar's Court at Agra and explored yet further into Burma and down to Malacca before returning to the Levant to resume his duties as a Levant Factor in Aleppo and Tripoli. Newbery was less fortunate, whilst travelling through the Punjab he disappeared, presumed murdered, and was never seen again. England's first attempts to reach out directly to India had ended in failure. The English had discovered for themselves that the economic stakes were too high and that England was not yet in a position to challenge Portuguese power in the region. The Levant Company went back to dealing directly with the Ottomans and conducting trade primarily through the Mediterranean. Ralph Fitch would later by approached by the founders of the East India Company as an adviser. He was able to give them valuable advice on trading with the Indian sub-continent and in particular extensively consulted with the explorer James Lancaster who commanded the East India Company's first expedition to the Orient.

The Levant Company itself provided a steady income to its investors for many years. King James renewed their Charter in 1605 in the name of: Company of Merchants of England trading to the Seas of the Levant. The company's trade grew steadily in the early years of the Seventeenth Century but there was one event that would have long term consequences. In 1619, Shah Abbas of the Persian Empire granted trading privileges to the English East India Company and allowed it to set up a factory in Bandar Abbas (Gombroon) - on the opposite bank of Gulf from the the Hormuz factory contemplated by the Levant Company. Although the Persian Empire was on the far side of the Ottoman Empire, the fact that the EIC could load their cargoes into ships and bring them directly to England meant that the Levant Company's markets would be under threat. However, this was only a small inconvenience in the short term and as the Levant Company's profits continued to gorw it largely overlooked the threat from the EIC. Of more immediate concern was how to negotiate the political turmoil that resulted in Civil War back in England in the 1640s. This was done with some skill as both Parliamentary and Royalist forces were content to let the trade continue to fund their coffers when they were each respectively in the ascendant. The delicate tiptoeing through the minefield of allegiances was confirmed after the fall of the Commonwealth when Charles II reissued the Company's Charter in 1661. The English were also able to gain privileged access to the Ottoman Empire in 1675 with an agreement that gave them more preferential rates than any other European power. However, the cloud of the East India Company continued to surely but steadily darken for the Levant Company. The East India Company was slowly expanding its power and influence by its maritime route around Africa. It had long struggled with both Portuguese and Dutch competition for the right to trade in Asia, but the goods that it brought back directly to England directly challenged the monopoly rights awarded to the Levant Company. There was also increased competition from the French who themselves were interested in dealing directly with the Ottomans. 1693 saw the French destroy a huge convoy of over 400 English and Dutch merchant ships heading to the Levant to trade. Competition was intensifying and in the Seventeenth Century, this often involved violence.

The Eighteenth Century saw the Levant Company's monopoly under threat in Parliament as MPs lobbied for lower prices and the right for other merchants to buy goods from alternative sources, such as from Italian merchants who charged lower rates. Political problems spilled over into open warfare when the Ottoman and the Persian Empire went to war with one another in the 1730s. This disrupted the silk and carpet trade which came largely from Persia and which had become one of the most important commodoties for the Levant Company. French competition and influence in the region continued to increase largely at the expense of the British factors. Westminster finally oversaw an expansion of membership to the Levant Company in 1753 in order to increase competition and the flow of goods between Britain and the Levant. Unfortunately, the timing could hardly have been worse for the company as India was about to be thrown open to the English for trade via the East India Company which won a devastating victory at Plassey in 1757 which secured a century of political and maritime domination for the company. The Levant Company slowly withered and increasingly had to lobby Westminster for funds to keep its dwindling factories and diplomats in place and in business. The French Revolution and nearly twenty years of warfare in the Mediterranean in the form of the Napoleonic Wars further hammered nails into the Company's coffin. In 1825, it dissolved itself after the British government made it clear that it could no longer subsidise a monopoly. This brought to an end over two centuries of mercantalist trade with the Middle East. The era of mercantalism and monopolies were drawing to a close and the era of Free Trade was about to open up new opportunities and relationships.

| | The Middle East as Transit Point | |

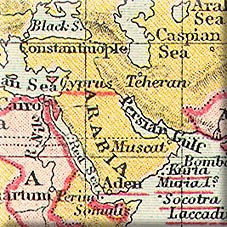

During the Eighteenth Century, the East India Company became increasingly important to the British economy. It had long relied on bringing goods from India to Britain via the maritime routes around the Cape of Good Hope. However, after it took control of Bengal it was effectively taking on administrative and governmental responsibilities as well as its commercial ones. This meant that communications with London would take on an increasingly important role as the more efficiently that messages and personnel could pass between India and Britain the better for the governance and administration of the territories. There was always the option of taking the long sea route alongside EIC goods rounding the Cape of Good Hope. However, it was also obvious that a ship could travel from Britain through the Mediterranean where passengers and messages could alight in Egypt. They could even travel up the wide and deep Nile to Cairo from where they could then make a fairly short journey through the desert to the town of Suez on the Red Sea coast and then catch another ship on to India. This route was too awkward for bulky goods but shaved off a significant amount of time for individuals and communications. Another, although longer option, was to alight in Syria or Lebanon and cross the desert to Basra and take a ship from there through the Gulf to India. This second route was more frequently used when there were difficulties and problems in Egypt - such as Napoleon's invasion in 1798.

Both the East India Company and the British government were interested in securing this Middle Eastern avenue of communications decades before the Suez Canal was even considered. The British took Gibraltar and Malta as important bases to guard the Mediterranean route to Egypt whilst the East India Company showed interest in a number of islands and ports on the Red Sea route to Bombay. However, it was the arrival of Napoleon in Egypt which galvanised the EIC into action. They sent an expedition under Lieutenant-Colonel John Murray to ascertain suitable bases to prevent Napoleon from travelling further towards India. He landed a force in 1799 at Perim Island with a view to using it as a base to project power into the Red Sea. Unfortunately its lack of potable water made it impractical longterm as a military base. The British government also signed the 1801 Anglo-Persian Treaty designed specifically to keep France (and Russia) out of Persian politics and prevent French and Russian movements further into the Levant. In the end, Napoleon abandoned Egypt particularly after the Royal Navy had inflicted a crushing defeat on the French Navy at Aboukir Bay. Combined British and Turkish forces defeated the remnants of his revolutionary army there in 1801, reducing the necessity of acquiring new bases in and around the Red Sea for the time being.

As Napoleon's armies were increasingly successful in Central Europe, he was able to ingratiate himself with the Ottoman Sultan from 1806 in return for helping to suppress Serbian rebels and to help the Turks capture territory from the Russians. Emboldened, the Turks closed the Dardanelles Straits to all warships but the French and helping launch the 1807 Anglo-Turkish War. The British despatched Admiral Duckworth to force a passage through the Straits of the Dardanelles, defeat the Turkish fleet and bombard Constantinople. The problem facing Admiral Duckworth were the vagaries of the wind in the era of sail. He was actually able to sail his ships through the Dardanelles where they were fired upon but passed through safely. They then proceeded to engage a small Turkish flotilla in the Sea of Marmora. However, his instruction to bombard Constantinople and seize the Turkish battlefleet revealed the limitations of his naval squadron. More difficulties with the wind and the reluctance of the Turkish fleet to leave the safety of their port and covering guns ultimately doomed the venture. The return trip through the narrows was even more dangerous than the journey in for the Royal Naval ships as the Turkish were by now prepared and were aided by French advisers. Although Admiral Duckworth lost no ships, they did take serious casualties evacuating the Straits. A second attempt to undermine the Ottomans took place in August when 5,000 troops were landed in Alexandria. This too achieved little for the British who were hoping to find a great deal of disatisfaction against the newly installed Viceroy of Egypt, Mohammad Ali. If anything, it helped to consolidate the young leader in his position. Over the following years Mohammed Ali would grew in power and stature to such an extent that they were able to take gain considerable autonomy from a steadily declining Ottoman Empire. Much of Britain's involvement in Egypt over the first half of the Nineteenth Century revolved around Britain's attitude towards Muhammad Ali and his relationship to the Ottoman Empire. Muhammad Ali was a talented populist who genuinely challenged Ottoman hegemony in the region. Britain was suspicious of his motives for most of his time in control of Egypt which lasted until as late as 1849. They preferred a docile and easy to dominate Ottoman Empire over an increasingly ambitious and vigorous Egypt under inspired leadership.

The Persian Gulf provided Britain with a different set of Imperial pressures. Lacking the strategic importance that oil bestows upon the region in current days. The Persian Gulf was one of the points of a rich Indian Ocean trade triangle. Trade had long prospered between West India, the Gulf and East Africa. Britain's rising domination in the Indian sub-continent meant that it took on the responsibilities of continuing this trade triangle and ensuring its security. The primary threat to this trade flow was through piracy. Arab pirates in particular attacked Persian and Indian ships with little remorse and could retreat into the deserts with their ill gotten gains. The British also demanded that local rulers attempt to suppress piracy although these rulers' willingness to sign agreements to do so were not always matched by an equal vigour to confront any pirates operating out of their region. The fact that most of the coastline was made up of competing sheikhs and emirs who were constantly in competition with one another meant that they were often unwilling to deprive themselves of a potential source of income or shed too many tears at their neighbouring rulers travails. The most powerful ruler in the region was the Sultan of Muscat who had a considerable navy and merchant fleet of his own. The East India Company signed a treaty with the Sultan of Muscat in 1798 shortly after Napoleon's arrival in Egypt heightened defence concerns for India. This was very much a treaty of equals showing the British preference at this time to exert informal influence and seek partners. She was primarily concerned that the waterways were free for trade and navigation. The Royal Navy had little interest in ruling peoples in parts of the world with few natural resources or agricultural capacity of note.

Napoleon's arrival in the region also upset the delicate political balance of some of the other Gulf arab rulers and particularly in the case of Trucial Oman where Britain was supported by one dynasty, the Al-Busaids, but in doing so became the enemies of their rivals the Qawasim. This meant that British East India Company ships became fair game and were attacked and pillaged at every opportunity by the Qawasim. This stretch of coast soon came to be known in Britain, India and beyond as the Pirate Coast and the Royal Navy reacted accordingly by launching campaigns and raids against the Qawasim in 1805, 1809 and 1811. Unfortunately for the British, the locals knew the area too well and could quickly escape only to regroup elsewhere. Upon the ending of the Napoleonic Wars, the British could turn their full attention to this disruptive part of their communications lines. A large British fleet was despatched to the Gulf in 1819 to attempt to stamp out the piracy once and for all. In a sustained campaign that stretched into 1820, the British destroyed and captured every Qawasim ship that they came across and occupied all the major forts in the area, even going so far as occupying Qawasim hideouts in the Persian Empire itself. This high handed but successful operation was completed by the British imposition of a General Treaty of Peace on nine Arab sheikhdoms in the area and the installation of a permanent garrison and force of ships in the region. This particular campaign marked the beginning of Britain's enduring presence in Gulf Region.

Not all piracy was connected to politics and allegiance. Much of it revolved around the availability of suitable high value targets. For example, slaves were brought primarily from East Africa to the Middle East where they were sold and exchanged for goods that were then transported to India in the Indian Ocean's very own Triangular Trade system. This meant that high value cargoes plied the seas with regularity which pirates took advantage of. Pirates often became a part of this slave trade as they sought to sell off their stolen cargoes or intervened to acquire slaves from the crews and passengers of ships raided. As the pirates became more successful, over time they turned their attention to yet more lucrative targets such as European ships carrying their valuable cargoes around or over the Indian Ocean. The role of the Royal Navy in suppressing pirates and slaving ships consequently increased throughout the Nineteenth Century as the value and quantity of shipping increased commensurately.

Religious sensibilities in the area meant that the British generally preferred to exercise their power through discrete means. Diplomatic staff preferred to work through proxies and sympathetic leaders; sparingly requesting the backing of the Royal Navy for any shows of force required. This meant that the Persian Gulf was effectively governed by a single flotilla of ships and a handful of political advisers. This area became one of the stablest of the Imperial realms with just fine tuning to the rights and obligations of the rulers and the British throughout the Nineteenth Century. It was really only the discovery of oil in the Twentieth Century which disrupted the stability of the region, a subject that will be returned to later.

It should be remembered that the first half of the Nineteenth Century also saw a transition away from sailing ships to steam-powered ships. Steam ships could sail in a greater diversity of weather conditions and could also work against tides and up rivers. The only downside was that they required coal which was heavy to carry but essential for power. This new technology created a requirement for regularly spaced out coaling stations along the communications routes. In 1835, the East India Company signed an agreement with a local Sultan in the South of Arabia to use the port of Aden as one such coaling station for the Red Sea route. Putting this agreement into place proved more troublesome than expected as other locals, including the Sultan's own son, were nervous at the arrival of European ships and that it might make prosecution of local piracy more difficult. Moves by the Egyptian leader of Muhammad Ali, with French backing, to try to seize the Yemeni port of Mocha saw an EIC expedition despatched to Aden in 1839 to seize the well placed port for the Company. It was actually the very first imperial acquisition of Queen Victoria's reign. Aden's importance would only grow as the Sinai route became more and more popular. In that same year of 1839, Mohammed Ali permitted a British Engineer Officer, Lieutenant Waghorn, to formally organise steamships to sail up the Nile to as close as possible to the port of Suez and then laying on carriages and camels for the overland connection. It was to fall to Muhammad Ali's grandson Abbas to grant permission for the construction of a railway, the first in Egypt (indeed the first in Africa or the Middle East), to connect Alexandria to Suez to speed up this transit process yet further. Robert Stephenson, no less, was contracted to build this first railway in the Middle East and also the first in Africa. Its standard gauge further revealing the British connection. This new railway considerably speeded up and eased the transfer of foot passengers and communications after its completion in 1858. Of course the opening up of the Suez Canal itself in 1869 further transformed this route for goods and personnel alike. The subsequent increase in maritime traffic saw the British show interest in other islands along the route such as Kamaran Island, Socotra, Kuria Muria Islands and a return once again to Perim Island which found a new lease of life as a coaling station for deeper draft ships in the second half of the Nineteenth Century.

Egypt's significance to the British Empire expanded greatly as the Suez Canal neared completion. It did not help matters, that the endeavour was largely financed and constructed by Britain's imperial rival of France. Unfortunately, the construction of the canal helped strain Egypt's finances to breaking point. Britain, and initially with France, felt compelled to intervene in the affairs of this state as its strategic importance for Britain escalated so rapidly with the completion of the canal. It would soon become the highway between the metropolitan state and its jewel in its imperial crown. Egypt had unwittingly transformed its position to the British from being a useful transit point to a vital concern that the British felt compelled to defend and secure.

| | The Middle East As Defensive Bulwark | |

In the Nineteenth Century, there were two primary imperial imperatives as far as the Middle East was concerned. One was the protection of imperial trade and particularly with regards to maritime trade. The other was the defence of Britain's most important colony, that of India. Indeed, it had been the East India Company who had first made the forays into the Persian Gulf with its trading forts in Bandar Abbas and Bushire. Furthermore, it had been the East India Company which had sought to take control of Aden in the curious example of a British colony taking its own colony in order to improve its defensive capabilities and without the prior authorisation of London. The Bombay Presidency need not have worried on that latter account, Aden's seizure was more than easily sanctioned by the British Government as its location helped fulfill both priorities of defending trade routes and the approaches to India. It also fit well with the popular pressure at the time to subdue slavery and stamp out piracy.

As India's borders expanded and its importance magnified, its defence priorities evolved and changed throughout the Nineteenth Century. As has already been mentioned, Napoleon's arrival in Egypt had already brought concerns for the safety of India to the fore. The French threat was temporarily removed after 1815, but this was only temporary and it would be supplemented by the much longer term threat of Russia as Russia's own imperial ambitions into the caucasus and the khanates of Central Asia seemed to place it on a collision course with Britain in the sub-continent as she herself moved further North and West into the Sindh and the Punjab. As the two European empires edged closer towards one another in the game of shadows that would come to be known as 'The Great Game', the primary land defence concern for the British was that an invading army to India might invade via Persia with its relatively flat terrain, certainly compared to the Himalaya route, and relatively more secure sources of water, food and fodder for any invading army. The status of the two Middle Eastern Empires of the Ottoman and Persian Empires therefore became an ongoing concern and concentrated Britain's primary Asian priorities towards the Middle Eastern region - even before the opening of the Suez Canal magnified the region's strategic importance yet further. It did not help that the British regarded both empires as being relatively inefficient, corrupt and unlikely to stand up to a modern European army over a sustained period of time. A series of wars between Russia and Turkey in the 1820s and 1830s merely amplified concerns for the defence of India.

Back on the shores of the Mediterranean, Britain's sympathies tended to lie with the struggling but strategically important Ottoman bulwark over the relative dynamism of Muhammad Ali's Egypt. When Muhammad Ali clashed with Ottoman troops in Syria as he sought to expand his influence at their expense, the British initially hesitated in supporting the Ottomans for fear of giving the Russians an excuse to meddle further in Middle Eastern affairs. The series of unsuccessful wars between the Ottomans and Russia had already weakened the Ottoman Empire and in 1833 they had been forced to sign a Treaty with the Russians which included a provision to close the Dardanelles to British and French warships whilst allowing passage to Russian ones. Anglo-Russian relations reached a nadir over the Vixen Affair in 1836 when a British diplomat, David Urquhart, was accused of aiding forces resistant to Russian expansion in Circassia. Britain went so far as to threaten war with Russia and both sides mobilised forces in the region. The issues subsided temporarily but this event and concerns for the defence of India went some way into causing the British to send an ill-fated expedition to Afghanistan in what became known as the First Afghan War of 1839 - 1842 and later still open conflict with Russia in the Crimea. In 1841, Britain managed to largely neutralise the Ottoman Turk agreement to deny British and French use of the Straits by holding a Convention in London from 1840 to 1841. This ultimately agreed that the Straits would be closed to all foreign warships as long as the Ottoman Empire was at peace. This actually had the effect of bottling up the Russian Navy in the Black Sea far more effectively than any restrictions on the Royal Navy which had free reign throughout the Mediterranean and could still access the Black Sea via the Straits should the Russians and Turks go to war with one another - as they did in the Crimean War the following decade.

Meanwhile though, Muhammad Ali was pushing his power and influence out of Egypt along both coasts of the Red Sea, into the Hejaz and up into Syria. Indeed, it was their relative successes in expanding into the Hejaz and turning the Red Sea into an Egyptian sea that had helped motivate the Bombay Government to seize Aden to allow at least a foothold against losing all influence along this important trade. However, despite the loss of Ottoman power throughout the region, Palmerston had been reluctant to incur the costs of propping up the ailing Ottoman Empire. However with the death of Sultan Mahmud II in 1839 and increased French interest in the Levant and a fear that they might join forces with Russia in extending both of their interests in the Middle Eastern Region set British alarm bells ringing once more. The defeat of the Ottoman forces to those of Muhammad Ali at the Battle of Nezib in Syria in 1840 and the humiliating defection of much of the Ottoman fleet to the Egyptian leader on the premise that his vigorous successes in modernisation and expansion presaged a growing new and more powerful Empire centred on Egypt rather than Constantinople, forced the British to intervene decisively. The British, under the forceful diplomatic lead of Palmerston, put forward the Treaty of London proposition to Muhammad Ali. Britain, in concert with Austria, Russia and Prussia - but pointedly not the French, would agree to recognise that Muhammad Ali was indeed the rightful ruler of Egypt rather than someone who had seized power illegally and that his heirs would succeed him after his death. In return for this recognition, Muhammad Ali was to abandon Syria and hand over the Turkish fleet back to Constantinople. Feeling that he would be sacrificing a winning hand for mere diplomatic recognition, Muhammad Ali declined the offer. He further hoped that he might have the support of the French. Faced with such intransigence, Palmerston gave permission to Admiral Napier to encourage rebellions along the various tribes and communities throughout the Levant and to land troops in concert with Ottoman forces to give material support in their insurrections. Actions at Jounieh, Beirut, Acre and Sidon and a blockade of his own port of Alexandria revealed to Muhammad Ali the hopelessness of the position of his forces against a determined and modern European power. Admiral Napier personally negotiated a modified version of the London Convention whereby he also agreed to evacuate Muhammad Ali's besieged forces from the Levant in addition to honouring the recognition of Muhammad Ali as the rightful ruler of Egypt and for his heirs to succeed him (which they did until as late as 1952). The Ottoman Empire had been preserved once more and the potentially more dynamic Egypt had been contained for the time being.

In return for British support against Muhammad Ali, the French and the Russians, the Ottoman Turks had agreed in 1838 to grant Britain preferential trading rights and to end their reliance on monopolies and charters to raise revenue. This was principally aimed at Muhammad Ali who was much more successfully raising revenue via these methods than the relatively corrupt Ottoman officials were able to achieve. However, it also had the effect of giving Britain (and later other European powers) the ability to access the considerable market with a nominal import fee of just 3% for imports. In many ways this was the culmination of the Palmerston doctrine opening up new markets for British products without the expenses and effort of taking formal control of territory. This commercial treaty supplemented and augmented the various capitulations that had been built up by European merchants since the 16th Century whereby Europeans could avoid

local prosecution, local taxation, local conscription, and the searching of their domicile. This privileged judicial and economic status would cause long term resentment against successive Ottoman Sultans and those Europeans enjoying their enhanced status. The consequent fall in income for the Sultan and the increased competition with local industries further undermined what was already a struggling Empire. In the short term though, it greatly benefitted British trade which could now trans-ship its products through and into the Ottoman Empire at very competitive rates.

The British intervention in the Crimean War from 1854 to 1856 was yet another example of the British coming to the aid of the declining Ottoman Empire in an attempt to keep Russian influence away from Constantinople in particular and the Middle East in general.

However, Britain's patience with its other bulwark to Russian expansion, the Persian Empire, was coming to its end. The Persians had renewed their own ambitions in Afghanistan at a time that the British felt that Russian influence was growing both in Central Asia in general but in the Persian Court also. The Persians wished to reclaim the town of Herat in modern day Afghanistan but the British were concerned that this might upset the delicate tribal balance in the region and might bring Persian, and hence Russian, influence closer to the important passes any invading army would need if marching to India. Unwilling to commit forces through Afghanistan due to their recent defeat there, the British responded instead by seizing the Persian port of Bushire in the Persian Gulf in 1856. The British then used this as a base to send an army into Persia and sent yet another force into Southern Mesopotamia. This determined demonstration of force convinced the Persian Shah to back down and abandon the city of Herat, to sign a commercial treaty with the British and to promise to help suppress slavery in the region. It should have had the effect of confirming British power and prestige in the region, but this was largely undone by the almost immediate outbreak of the Indian Mutiny.

The replacement of the East India Company by the British Raj did little to change Britain's attitude to putting a primacy on defending India and to continue to be suspicious of Russia and France in Central Asia and the Middle East. As discussed elsewhere, Britain was concerned at French influence in Egypt and especially with the building of the Suez Canal. She was also still hostile to ever growing Russian influence in Central Asia and once more came to the defence of the Ottoman Empire in the 1877 - 78 Balkan Crisis. This particular crisis had seen Russia in a particularly strong position at its outbreak, so much so that the Ottomans became utterly dependent upon Britain's aid to help protect her from Russian ambitions. Upon its conclusion, the Sultan promptly gave Britain the island of Cyprus partly as a form of gratitude, but also as a way of tying Britain and the Royal Navy into the Eastern Mediterranean in the hope that Britain would continue to aid the Ottoman Empire against Russia in the future. This island of Cyprus would actually be very well placed to extend Britain's regional influence especially as it lay close to the approaches of the Suez Canal. Indeed, Cyprus was used very much as a base for the British campaign into Egypt in 1882 and the legacy of this gift has lasted right into the present day as the British still have military facilities on the island some century and a half later. Combined with her naval bases in Gibraltar and Malta, Cyprus allowed Britain to maintain its pre-eminent Mediterranean maritime dominance. This became more important as the Suez Canal magnified the importance of the Mediterranean with regards to international and especially imperial trade. So in a happy coincidence of aims of securing India and securing the maritime trade routes came together with Britain's expanding interest and intervention in the Middle East. At this point in time though, Britain was still largely relying on informal influence, client empires and the occasional bases for the Royal Navy. There were few colonies of occupation and certainly none of settlement. What is peculiar about Britain's involvement in the Middle East is that it was the Indian Government, rather than Westminster, that was largely calling the shots for British policy in the region for nearly all of the Nineteenth Century. It would not be until the discovery and rising importance of oil in the Twentieth Century, that Britain's relationship to the region would change fundamentally.

| | Intervention in Egypt and the Eastern Mediterranean | |

Egyptian attempts to modernise itself had seen its economy expand markedly especially after the 1840s. Its principle export of cotton made it ideally suited to complement the burgeoning industrial mills of Northern Britain. European banks and capitalists were keen to lend money to an economy on the door of Europe with products that were much in demand and with significant markets of its own. Its location bridging Europe to Asia was also seen as a positive investment indicator. Modernisation was also seen as a way for the Egyptian rulers to out-develop their nominal Ottoman overlords. The rationale being that the more successful the Egyptian economy was, the more ability they would have to act independently and to release themselves from Turkish control. However, this modernisation came at an increasing cost as Egyptian finances struggled to pay for the lavish schemes undertaken. Investment in ports, railways and, most expensive of all, the Suez Canal put an ever greater strain on the Egyptian budget. Investments in irrigation and cotton production undertaken during the American Civil War when cotton prices reached abnormal highs also came to a juddering halt after the war ended. The Egyptian ruler Ismail (who actually purchased his title of Khedive from the Ottoman Sultan at great cost) also did not restrain his own lavish personal spending as he sought to westernise his court and undertake ever more lavish public works projects.

The inability of Egypt's finances to continue to service their debts became increasingly apparent in the 1870s. The need for liquidity saw Ismail having to realise one of his remaining economic assets of worth; his shares on the Suez Canal Company. In a highly unorthodox political response, the British Prime Minister leapt at the unexpected opportunity to join the largely French run organisation by seeking the necessary 4 million pound finance required from Lionel de Rothschild to buy the Canal stock. He was mindful of the inevitable delays that would have occurred going through normal British political channels and felt that the opportunity might be seized by a quicker and possibly even more dangerous rival bidder. Britain therefore, despite being so vehemently opposed to the construction of the canal, became one of its largest shareholders almost overnight.

This injection of capital was still not enough to satisfy Egyptian creditors and the country was officially declared bankrupt at the end of the 1875/76 financial year. Bondholders, primarily British and French, took control of Egyptian finances from 1876 as they sought to rein in expenses and maximise income. The effects of these policies was to further alienate Khedive Ismail from the Egyptian people who largely blamed him and his regime for their precarious economic predicament.

The reason for British intervention was to be found in the increasing unpopularity of Khedive Ismail and his inability to protect Egyptians of nearly all social classes from the economic consequences of their overspending and the policies of the 'Dual Control' bondholders in charge of Egypt's economic affairs. The Khedive made a last gasp to escape the clutches of his European creditors by fomenting an Islamic army to rise up and overthrow the Westerners he claimed were responsible for Egyptian pain. This deliberate attempt to destabilise the country was too much for the British and French overseers who requested that the Ottoman Sultan dismiss his representative in Egypt. The Sultan was happy to oblige and Ismail was duly replaced by his seemingly more compliant son, Tewfik. Yet more western 'experts' were inserted into Egyptian ministries and organisations in order to maximise returns and also reduce opportunities for articulate Egyptians at the same time. Indeed, the kernel of rebellion and resentment of oppression only increased. These sentiments found a leader in one of the few Egyptian Colonels in the Westernised army, Urabi Pasha. With the intervention of the Sultan, Urabi Pasha could call upon latent Egyptian nationalism to resist these outside meddling powers. Attempts to control Urabi were undone by loyal troops who rescued him after an arrest by Tewfik's soldiers. As the young Tewfik's powers seemed to be ebbing from this direct challenge to his rule, the British and French sought to consolidate his power through a show of naval strength. However, his reliance on overseas military might ended up undermining his authority rather than restoring it. Riots in Alexandria in 1882 saw Europeans amongst the casualties and cries for intervention from the Europeans running large swathes of Egypt's affairs. The Ottomans refused to intervene on the basis that the costs would be prohibitive and that their intervention might make matters worse. Therefore, the British despatched a fleet from their newly acquired base in Cyprus ostensibly to restore law and order in Alexandria but also to secure the all important Suez Canal route. They had been expecting the French to intervene alongside them but the French withdrew their support at the very last moment due to domestic political problems at home - this would later cause resentment between the two European powers. The British intervened alone and landed an army that defeated the rebellious Urabi Pasha at Tel-el-Kebir later that year.

The Liberal British administration had seemed reluctant imperialists and unclear as to how to extricate themselves from a sustained commitment in Egypt. The fiction that the British were acting on behalf of the Ottoman overlords was maintained through the fact that their representative was referred to as 'Consul-General' rather than as a 'Governor'. The watchword was to impose 'stability' on the country - both economic and political. It was argued by men on the ground like Consul General Baring that this would require time to achieve. It did not help that the neighbouring Sudan, which had been an Egyptian colony since 1822, had rebelled itself in 1880 during the chaos of Urabi Pasha's revolt. It had fallen largely under the control of the Islamist 'Mahdi'. Half hearted attempts to recapture the Sudan were undertaken in 1883/4 but Baring gave the order to evacuate the area in the interests of 'stability' and 'cost-cutting'. Unfortunately, the person chosen to achieve this evacuation was General Gordon. As a committed Christian he felt that he could not abandon Sudan's population to the harsh Islamic rule of the Mahdi and so took a unilateral decision to defend Khartoum and await relief from Egypt. This caused a political crisis back in Britain as the Liberals were criticised heavily by Christians in particular who were appalled at the government's lack of intervention. When Gladstone did finally agree to send a relieving force, it was too little and too late. The fact that it arrived in Khartoum just days after Gordon was killed and the city had been sacked seemed to confirm to many the incompetence of Gladstone's administration. This particular tragedy illustrated the difficulties in 'not intervening' as each new imperial addition seemed to add yet more imperial responsibilities and issues to deal with. The death of Gordon in Sudan also helped see the end of Gladstone's administration as it lost heavily in the next general election. The British government found for itself that even well intentioned interventions could have serious and unexpected repercussions.

| | The Rising Importance of Oil | |

With regards to Persia towards the end of the Nineteenth and beginning of the Twentieth Centuries Britain had gained some credibility in helping successive regimes resist increasing Russian expansionism. During the Great Game, Tsarist Russia was increasingly perceived as the greater threat from the two imperial powers. This was partly due to their more autocratic form of government but also because of their relative proximity and seemingly insatiable incursions southwards. Britain meanwhile appeared content merely with the defence of the Raj and had a more acceptable and responsive form of government. Such perceptions seemed to be confirmed when the British sided with Persian constitutionalists in a revolution in the country in 1906. This revolution had been at least partly inspired by the relative success of Japan in modernising itself and in defeating a European power, Russia no less. Unfortunately any goodwill fostered by the British for this support in 1906 was squandered the following year with the Anglo-Russian agreement to divide Persia into spheres of influence; A Russian Zone in the North, a Neutral Zone in the Centre and a British Zone in the South. This somewhat unexpected reversal had come about due to the growing tensions in Europe and especially the responses made by the Germans towards the Ottoman Turks. Britain had moved closer towards France and in consequence her old Great Game nemesis of Russia. The resolution of antagonising factors between Russia and Britain in the decade preceding World War One unsettled many in Persia and would lead some leading nationalists there to even consider joining with the Germans against the British - although any such suggestion was undermined when their traditional rival of the Ottoman Empire eventually threw herself fully into Alliance with the Central Powers in 1914.

However, the long term European interest in the region was transformed by William Knox D'Arcy's discovery of oil in 1908 in Persia. The discovery was something of a fortuitous event as his team had been prospecting since it had received a concession from the Shah of Persia in 1901 with little success and a cable from his directors cancelling any further exploration was already en route to the beleagured D'Arcy when he finally struck oil in Masjid i-Suleiman in southern Persia. The Anglo-Persian Oil Company was set up in 1909 to facilitate its extraction and new refinery facilities were constructed at Abadan.

The timing of this discovery could not have been more fortunate. International tensions in Europe were rising in this period. The German's had instituted a Tirpitz Plan to rival the power of the Royal Navy. In return, the Royal Navy underwent a massive building plan of its own, culminating in the creation of the new Dreadnought class of battleships. One innovation that caught the Royal Navy's attention was to use oil instead of coal to power its ships. Oil was relatively lighter, more responsive allowing for better acceleration and did not belch out such huge smoke stacks revealing the position of this ships from so far. The only problem was that Britain at this time in history had no secure access to oil of its own, although she had plenty of coal. The discovery of oil in Persia therefore caught the Admiralty's attention.

Winston Churchill took control of the Admiralty in 1911 and set up a Royal Commission on oil supply for the fleet. The historic decision to switch the Royal Navy from coal to oil was duly taken as steps were made to secure that flow of oil by taking a controlling interest in the Anglo-Persian Oil Company in July 1914 - just weeks before the outbreak of the First World War. In addition to taking a 51% stake in the company, the British government also secured a 20 year contract to supply oil to the Admiralty at highly favourable terms. It was actually a very far-sighted strategic decision for the Royal Navy but it also had the consequence of changing Britain's relationship to the Middle East as security of oil supply only became more important as the internal combustion engine increased in importance and other shipping followed the Royal Navy's lead. The Persian discovery also led to further exploration attempts in the region to see if yet more oilfields might be located and sure enough the geological conditions in the region were more than obliging.

The discovery of oil in Persia increased speculation that other deposits might be found in the region. The Turkish Petroleum Company was established in 1912 with largely British and European investors with a view of surveying for oil within the Ottoman Empire, principally in the Mesopotamian region. Unfortunately growing suspicion between the British and Germans leading ultimately to war in 1914 brought an end to such exploration especially after Turkey had sided with the Central Powers, however the company's fate would yet yield significant results.

The First World War only increased the demand for oil as Navy after Navy in particular saw the advantages of oil as a fuel for their ships and as the internal combustion engines exploded into popularity in both road vehicles and increasingly for aircraft. Britain controlled the only significant oil production outside of the Americas during the war through its control of the Anglo-Persian Oil Company. This had actually come close to being attacked and possibly neutralised by the Germans in the early stages of the war when the Germans embarked on one of the most ambitious diplomatic missions of the war under two German officers, Niedermeyer and Wassmuss. They were charged with travelling through the Middle East from Constantinople to Afghanistan with a message from the Caliph to rise up in Holy Jehad against the British infidels. En route, Niedermayer realised that the Abadan oil refineries were relatively unguarded and made elaborate plans to isolate and attack them. At the last moment though, the Kaiser himself over-ruled the attack for fear that it would reveal the existence of the mission and put the plans for a larger uprising at risk. As it transpired, Niedermayer would fail to inflame revolt on the borders of the British Raj, although Wassmuss, later referred to as the German Lawrence of Arabia, had a little more success in Persia. However, their isolation from further support and supplies and the British (and Russian) strength in the region and the control of the seas by the Royal Navy doomed their mission to failure. It should also be noted that the German High Command and the Kaiser had possibly yet to fully appreciate the strategic significance of oil when they over-ruled the attack on Abadan. It was a missed opportunity and one that would never again present itself to the Central Powers.

Persian Oil may have been the first to be discovered in the region, but it would later be joined by others transforming its strategic importance once and for all. The next significant oil discovery of note was by the Turkish Petroleum Company in the 1920s. At the 1920 San Remo Conference, the French had successfully lobbied to receive the German portion of ownership of this company in part as compensation for losses in the First World War. Consequently this joint British-American-French concern was given a concession to search for oil in 1925 and had struck a particularly large find in Kirkuk in 1927. One complication though was that the government of Turkey still claimed the region of Mosul as part of their Ottoman Empire and disputed its ownership by the Iraq Mandate government. The dispute lingered for many years in the newly formed League of Nations. However, as Britain wielded considerable influence in this new organisation and the fact that it was responsible for the financial security of the Mandate in Iraq, it lobbied hard to have Mosul permanently awarded to Iraq. Eventually after protracted wrangling and countless conferences the League of Nations finally awarded Mosul to Iraq much to the disgust of Turkey.

The 1930s saw yet more surveying activity throughout the Middle East. The next significant discoveries were in Kuwait and in Saudi Arabia which both discovered oil in commercially exploitable quantities in 1938. What set aside oil production in the Middle East from other parts of the world was its relatively low price for extraction. From an engineering perspective it was much cheaper to build the derricks and pipelines for oil which lay fairly close to the surface than building rigs out at sea or through complicated geological rock formations. And once again, another war would further increase demand for this commodity. Oilfields themselves began to be regarded as vital strategic concerns and began to alter the plans of planners and rulers alike.

| | The Ottoman Empire From Friends to Enemies | |

For much of the Nineteenth Century, Britain had been a staunch defender of what was often referred to as 'The Sick Man of Europe'. Britain had been prepared to overlook the problems of autocracy, corruption and inefficiency of the Ottoman Empire when compared to the much larger threat of Russian Expansion both towards the Jewel in the Crown of India and towards the Dardanelles and the Eastern Mediterranean. Britain had cultivated extensive diplomatic and trading relations with the Ottoman Empire during this Century and often had privileged access to the Sultan and key decision makers throughout their Empire. The Friendship of Britain was seen by successive Sultans as providing a layer of diplomatic and even military support against external threats to the Empire. As already mentioned, this began to change in the first decade of the Twentieth Century as Britain found herself as something of an unexpected Ally of Russia through her Entente with France and with a desire to contain the growing strength and power of Germany.

Britain's rapprochement with Russia in 1907 coincided with a key political event in the Ottoman Empire the following year with its Young Turk Revolution. The power of the Sultan was greatly diminished as younger and more virile Turkish Army officers came to the fore. Britain's long cultivated relations with the Sultan's Court suddenly meant very little as new Turkish leaders sought to distance themselves with the friends of Sultan Abdul Hamid and sought new aid and support. This was especially so after the Sultan had attempted to launch a Conservative countercoup of his own in 1909 to wrest back control. However this failed and the Sultan was forced to abdicate in favour of his more pliable brother as Sultan Mehmed V. British diplomatic officials in Constantinople were hostile to what they regarded as political upstarts and were convinced that they would not remain in power for long. A century of goodwill between the British and Turkish courts entered a period of suspicion. Early democratic, revolutionary and liberal claims by the Young Turks were soon seen to be a mirage as its leadership gravitated towards emulating militaristic regimes like Germany and Japan. This was confirmed in 1913 when the Triumverate of Enver Pasha, Talaat Pasha and Jemal Pasha seized control in a further coup.

The wave of nationalism that had helped propel the Young Turk revolution also unleashed other nationalisms within the mutli-ethnic Empire - particularly, but not exclusively, in her European lands. A series of Balkan Wars saw large tracts of the Ottoman Empire fight for their independence against a weakened Turkey undergoing profound political convulsions. In this context, the Ottomans found much more sympathy for their plight from the authoritarian Austro-Hungarian and German Empires than they did from the conflicted democracies of Britain and France. They were also historically suspicious of the motives of their long time regional rival Russia which had joined with Britain and France as part of the Triple Entente. German diplomats played on this innate hostility towards Russia and encouraged Turks to be wary of the Allied powers.

The Germans sought to curry yet further favour with this new regime by promising to provide military equipment and training and by subsidising the construction of a Berlin to Baghdad Railway which would have brought German influence into the heart Ottoman Empire and into the Persian Gulf itself. This plan actually predated the Young Turk revolution, but the increasingly obvious German involvement in the construction of key parts of the railway scheme only appeared to confirm that German influence was rising throughout the Empire and apparently at Britain's expense. The Germans also agreed in 1913 to send a German Military Mission to Constantinople to train and equip the Turkish Army - There was already a British Naval Mission in Constantinople training Turkish sailors who were soon expected to receive delivery of two British built warships. Enver Pasha, whose own political power had grown to first amongst equals in the Triumverate, was the principle catalyst for the pro-German stance. He had actually spent time in Berlin as the Turkish military attache and was proficient in German. He forcefully proposed the idea of a secret alliance with Germany (allegedly chairing the meeting with his revolver on the Cabinet table in front of him).

Although Enver Pasha was keen on a German alliance, most Turks were content for armed neutrality. The Ottomans had been exhausted by years of war by this point and its economy had not prospered in these years of uncertainty. Into this delicate diplomatic situation, no less a person than Winston Churchill, as First Lord of the Admiralty, accidentally riled Turkish emotions against the British. The issue was the two warships being constructed in British shipyards, one of which was completed in August 1914. The timing could hardly have been worse. Wary of sending additional naval capabilities to a potential enemy and also wishing to boost the Royal Navy's own complement of vessels, Winston Churchill took the fateful decision of requisitioning the two ships for the Royal Navy. This decision was taken on August 3rd the day before Britain declared war on Germany. An outraged Turkish cabinet soon found solace from the head of the German Military Mission, Liman von Sanders, who promised that the Germans would make good on replacing the ships. It just so happened that the Goeben and Breslau were operating in the Eastern Mediterranean. They were ordered to the Dardanelles. Had they retained their German flags, this would have been seen as an open declaration of support for Germany once they had entered the Straits. Therefore the fiction was created that these were Turkish ships. The German crews even went so far as to wear fezzes and change the names of the ships to the Yavuz Sultan Selim and the Midilli.

In August 1914, the Central Powers were still keen to keep their alliance to Turkey as a secret. They were confident of their own quick victory and did not wish to complicate strategic matters nor have to award Turkey any lands or spoils unnecessarily. The British Naval Mission was replaced by a German one and German advisers continued to arrive - amongst these arrived the Niedermeyer mission to Afghanistan mentioned above. British ships stopped a Turkish torpedo boat leaving the Dardanelles and when they discovered Germans amongst their crew ordered the boat back to port. In retaliation a German military commander took the decision to close the Dardanelles to shipping - breaking the London Convention on the freedom of navigation through the Straits. As Russian troops spilled into Eastern Prussia and the German Army met defeat on the Marne, the Germans reevaluated their reticence on activating their alliance with Turkey. The German crews on Turkey's new battleships slipped into the Black Sea in October and without warning opened fire on Odessa, Sevastapol and Russian shipping. This provoked the Russians into declaring full blown war on the Ottomans. The British and French stood up for their ally and bombarded some of the forts along the Dardanelles on November 3rd. Aqaba was shelled after the garrison refused to stand down and British forces landed at Basra to secure the Persian oilfields at Ahwaz. Britain and France formally declared war on November 5th. In retaliation, the Ottoman Empire declared Jihad a week later on November 11th. This dramatic sounding call for a Holy War against the infidels was hoped to inspire uprisings amongst British and French Muslim soldiers and civil disobedience from the Maghreb to India. In reality it achieved little in the short term with the exception of the response of the Senussi in Libya. The Italians had only recently wrested control of Libya from the Ottomans in 1911. 10,000 Senussi tribesmen had been secretly trained by the Ottomans since the loss of this territory. When the Italians finally joined the Allied cause in 1915, the Senussi took advantage and rose up. British and Italian forces had to be diverted to deal with this uprising and Senussi warriors penetrated into Egypt as far as Marsa Matruh. For a short while at least defenders of the the Suez Canal had to be diverted to this threat from the west.

Meanwhile, Ottoman forces seemed to concentrate their efforts against their historic foes the Russians. However in early 1915 they launched a surprise attack through the Sinai Desert to the vitally important Suez Canal. The German led operation achieved a measure of surprise but the British defenders were alert and responded speedily to the incursion. It helped that many Indians, Australians and New Zealanders were in transit to join the war in Europe when the Turks attacked. Indeed their subsequent presence in Egypt in such large numbers as a result of this Ottoman attack on the Canal was one of the reasons that planners considered seriously the idea of attacking the Dardanelles just a few months later. As it was though, the Ottomans had successfully extended their territory into the Sinai Peninsula even if they were unable to cut the Canal itself. The war had spilled over into the Middle East proper.

Both the Ottomans and the British attempted to woo Hussein bin Ali, Sharif of Mecca. The Ottomans claimed overlordship of the Hejaz and sought to keep their co-religionist Arab population loyal to the Empire. However, Sharif Hussein was resentful of the growing power of the Young Turk Ottomans who were beginning to prove more efficient in their administration than the previous Sultan's regime had managed. Nevertheless, the British were hesitant in encouraging the Sharif too much too soon. They wished to coordinate their responses with their French and Russian allies and they were also initially confident of their own military capabilities to win the war in the region quickly and efficiently, hoping that the Dardanelles campaign would knock Turkey out of the war once and for all.

The threat to the Suez Canal combined with pleas from the Russians to supply aid to them in their fight against both the Ottomans and the Germans. This led to the ill fated Gallipoli Campaign to seize the Dardanelles Straits by force. Once again, Churchill played a pivotal role in this bold plan but unfortunately did not choose leadership that was commensurate to the task ahead of it. Initially the Royal and French Navies had come tantalisingly close to forcing the narrows before mines and shore batteries took their toll on the large battleships involved. On April 25th, forces were landed at Cape Helles and what would become known as Anzac Cove in what was actually the largest seaborne invasion in history at that point. Poor planning and lackadaisical leadership squandered opportunities for success although the Turkish soldiers found heart in defending their homelands and fought fiercely under overall German command. Reinforcing the landings with new troops at Suvla Bay just prolonged the agony as yet more opportunities were missed by the Allied forces. The only bright spot in the campaign was the eventual evacuations which showed an imaginative flair, leadership and the kind of coordinated planning that had been sorely lacking previously. The strategic imperative had diminished the Turkish threat as the Russians provided a shattering defeat to Enver Pasha over at Sarikamis on the Russian border. Unfortunately, Enver Pasha deflected his own role in this shattering defeat by using Christian Armenians as the scapegoat for their defeat. The Ottomans unleashed a lethal genocide against this minority within their borders.

The Indian Army took control of another assault on the Ottoman Empire as the fighting in Europe bogged down into trench warfare. The British had already seized control of the Persian Gulf and its important oil supplies as far as Basra before General Townsend was tasked with advancing to Baghdad. In April 1915 he was making good progress before he met a large Turkish force under German command at Ctesiphon just 25 miles south of Baghdad. The battle was inconclusive but demonstrated that Ottoman strength was increasing as his own army stretched its own supply lines. Rather than make a last dash towards Baghdad, Townsend decided to withdraw to Kut on the River Tigris. This was a fateful mistake which allowed the Ottomans the opportunity of surrounding his beleaguered forces. Three attempts to break out were rebuffed and attempts to run supplies past the besiegers similarly failed. Disease, hunger and thirst depleted the defenders more effectively than any Turkish assault could have managed. Eventually Townsend capitulated in one of the largest setbacks of the war. Townsend himself was marched off to comfortable captivity whilst most of his forces suffered terrible privations and with too few surviving to tell the tale. This was a nadir of British prestige in the region during the conflict.

A new commander was given the opportunity to atone for the setback at Kut. General Maude began a new offensive in December 1916 up both banks of the Tigris. He recaptured Kut in February 1917 and pushed on to capture Baghdad in March. There were further probes to the North, but operations were wound down as the focus switched to Palestine.

July 1916 saw the Turks threaten the all important Suez Canal a second time using troops who had been freed up from the Gallipoli theatre. Further fierce fighting convinced the British of the merits of launching an offensive across the Sinai to create a larger buffer zone for the canal. Ostensibly this was to be supported by the Arab Revolt in the Hejaz although in reality this revolt did little to directly aid the British other than to tie down Ottoman troops and supplies in garrison duties and protecting the communications lines. The British Sinai offensive captured Maghdaba close to the Palestine border in December 1916. A second offensive was launched by the British in March 1917 outside Gaza. This failed to dislodge the Turkish defenders. A second attempt in April similarly failed to break through. More troops were provided and some subterfuge was resorted to as an officer 'lost' a haversack with misleading plans for the Turks to find. The British actually planned to attack Beersheba rather than Gaza directly for a third time. The Turks fell for the ruse and were caught off guard. Gaza fell shortly after and the Turks began a headlong defeat which culminated in the British entering Jerusalem in December 1917.

The Russian revolutions in 1917 saw one of Britain's most important regional allies first disappear and then reemerge later as a new rival in the region in its Communist guise. In the short term though, the Russian collapse allowed the Ottomans to shore up their defences in early 1918 and redeploy troops from the Caucuses. The stunning German success in Western Europe in the Spring of 1918 also caused consternation to the Allies as troops and resources were hurriedly diverted to the Western Front. General Allenby's army had to wait until September of 1918 before it could resume its full offensive capacities. By this time, Lawrence's Arab Revolt was proving much more strategically useful as they moved up from the Hejaz into Palestine and the Transjordan. Damascus fell on October 1st 1918 symbolising the beginning of the end of the Ottoman Empire. Her remaining rulers and military leaders frantically attempted to preserve Turkey proper even whilst realising that her colonies would be lost forever.

Like the Germans, the Turks took heart from Wilson's 14 points which included a provision to say that the Turkish portion of the present Ottoman Empire should be assured secure sovereignty. However, the United States had specifically excluded themselves from any involvement in this theatre of operations and were to play no role in the resulting peace treaties relating to Ottoman lands whatsoever. The French were also somewhat sidelined. Notwithstanding their own involvement in the Sykes-Picot agreement (explained below) earlier in the war and in providing troops in Gallipoli, along the Suez Canal and in supporting the Arab Revolt, Lloyd George felt that as Britain had provided the lion's share of men and material that she should have the definitive role in the armistice and resulting peace negotiations. Consequently, Britain's plenipotentiary, Admiral Calthorpe, was instructed to sideline the French representative. This led to early mistrust between the ostensible allies. Turkey signed the armistice on October 30th 1918 and agreed to the Allied occupation of the Dardanelles. Some 40,000 British troops landed in Constantinopole, the Gallipoli Peninsula and the Dardanelles Straits which had been so drenched in Allied blood just a few years earlier. However, the British had agreed not to occupy Constantinople nor Turkey proper outside of the Dardanelles and some forts along the Bosphorus. The Ottoman Empire had been swept away - her colonies would be reallocated accordingly and a resentful Turkey would provide new challenges in the years to come.

| | Conflicting Promises and Realities | |

Although ultimately victorious, the British had entered into a number of conflicting promises as to what the post-war settlement would look like with regards to the Ottoman Empire's colonies and area of influence. Britain and her colonies had played by the far dominant role in the Allied commitment to the fighting in the Middle East. France had initially committed significant ships and soldiers to the Gallipoli Campaign, but as the fighting in France became more desperate so French influence in the region declined. The French also played a significant role in the nearby Macedonian Front. The Italians offered little beyond defending their territory in Libya from the Senussi tribesmen and even there did little other than garrison their ports and forts and performed badly. Fighting the Senussi fell overwhelmingly to the British and Indian troops of the Empire.

The conflicting promises revolve around a number of distinct and to some extent mutually exclusive commitments made during the fighting of the war. It is important that the strategic situations of the war at the point of the various commitments are taken into consideriation in order to understand why they were pledged. There is also the fact that all three commitments are couched in vague and often diplomatic language that provided for more latitude and leeway than is often appreciated. Indeed, none of the three commitments made were ever fully implemented. They all were sufficiently vague as to offer subsequent diplomats and politicians the opportunity to modify, compromise and tailor later arrangements.

The first commitment was made to the recent enemy of the Turks over in Libya; the Italians with the Treaty of London in April 1915. This was essentially a giant bribe to win the Italians over from the Triple Alliance to fight on the side of the Allies. Although the lion's share of territory on offer was at the expense of Austro-Hungary, there were also clauses assigning the Italians lands in Anatolia and also in respect to increasing her colonies. Article 13 stated: In the event of France and Great Britain increasing their colonial territories in Africa at the expense of Germany, those two powers agree in principle that Italy may claim some equitable compensation.' It seemed likely that these would have to come at the expense of the Ottoman Empire as she was the only other Central Power with colonies to confiscate.

The McMahon-Hussein correspondence appeared to be the most generous offer to the Arabs. As mentioned previously, the British had initially sought to defeat the Ottomans without aid from local groups, but as the Gallipoli Campaign failed and the Mesopotamian Campaign ended in disaster at Kut and the threat to the Suez Canal was far from removed, the British reconsidered this position. The British High Commissioner of Egypt, Sir Henry McMahon, entered into correspondence with Sharif Hussein of Mecca. Egypt was already suffering from the privations of war and its inhabitants were thought to be the most susceptible to the Ottoman Sultan's calls for Jihad. McMahon's Oriental Secretary, Ronald Storrs, came up with the ingenious plan of approaching the guardian of the Islamic Holy shrines and a direct descendent of the prophet as a way of blunting this call for Jihad. It helped that they could also provide material aid in fighting the Ottomans especially in the exposed Hejaz. Storrs even went so far as to suggest that Hussein could replace the Ottoman Sultan as Caliph after the fall of the Ottoman Empire. McMahon was given vague instructions from London who were also considering the latest French proposals for influence in the same locations as Hussein was claiming in his initial correspondence with Storrs. The fact that the Ottomans were preparing for a new offensive against the Suez Canal and that the Arabs were themselves being approached by the Central Powers to support them gave some urgency to McMahon's and Storr's negotiations. McMahon was given discretion to decide on the spot but he did take Whitehall advice to be vague as possible in his commitments. He therefore said that Britain would recognise most of Hussein's claim with the exceptions of the Head of the Persian Gulf (where the British already had its Mesopotamian Front based) and an even vaguer exception of the coastal portion of Syria which the French had already requested. Basically McMahon had offered Hussein lands in which the British would have had influence but neglected to clarify that no such promise could occur in areas that were separately being discussed and finalised with the French. The correspondence petered out but in reality the disagreements were set aside for discussion at a later date. However, the British and French had already embarked on their own and very separate negotiations and in which McMahon played no role.

It was the French who were far more hostile to the idea of any Arab state and even the idea of a British backed Arab state neighbouring a French colony caused them consternation especially with the French plenipotentiary, Georges-Picot. The French were conscious of the blood and treasure they were haemorrhaging in waging war against the Central Powers and saw acquiring colonies as one way to mitigate these costs in the future. The British had their own strategic designs in the area revolving primarily around Imperial Defence and securing the lines of Communication through the Middle East to India. Mark Sykes on behalf of the British agreed with Georges-Picot to divide the Ottoman lands into two distinct spheres of influence - a French (or blue zone) and a British (or red zone) stretching from Haifa to a midpoint between Mosul and Kirkuk in Mesopotamia both known for their oil supplies. This division between the French and British zones was later tagged as the line in the sand. Intriguingly, neither power could agree on the status of Palestine which was left as a brown zone which was supposed to represent an area that would come under joint international control. The agreement was ratified by both governments in May 1916. This Sykes-Picot agreement was kept secret for fear that its contents would inflame, complicate and contradict the assurances given to the Arabs in particular in return for their support against the Ottoman Empire.