|

Just how old is Singapore?

|

|

Fifty? Nearly two hundred? Or some seven hundred years old?

Even as historians and nation-builders debate the intriguing question, and as political leaders of the day set about to map out the future, it is worth remembering that the past fifty years of stunning progress and development on the island Republic never happened in a vacuum. In fact, the first leaders of independent Singapore had inherited a working political and economic framework from a colonial administration skilled at running an empire for several generations. Today, as the nation crosses the threshold and moves on from the crucial and significant “jubilee” juncture, this article seeks simply to restate what is at risk of being forgotten, that a lot happened in Singapore before SG50.

"For the short period it has been in existence, Singapore is, without an exception, the most thriving colony which the British have in the East Indies... Within the last ten years, this place has increased and flourished beyond all calculation. An Indian village of forty or fifty bamboo huts has given place to a splendid well-built little city."

(Benjamin Morrell, A Narrative of Four Voyages, 1832)

"We live in a world that empires have made. Indeed, most of the modern world is the relic of empires: colonial and pre-colonial, African, Asian, European and American. Its history and culture is riddled with the memories, aspirations, institutions and grievances left behind by those empires. The largest if not grandest of these was the empire laboriously assembled by the British across more than three centuries. No less than one quarter of today’s sovereign states were hewn from its fabric. For that reason alone, its impact was second to none.”

(John Darwin, Unfinished Empire, 2012)

“The British Empire is so misunderstood.”

(Bernard Porter, British Imperial: What the Empire Wasn’t, 2016)

|

|

Introduction

|

|

In the wake of the exuberant jubilee celebrations that gripped Singapore in 2015, it almost seems inconsiderate to remind ourselves that Singapore is a lot more than fifty years old. But it is. Isn’t it? Otherwise we have made a mockery of all our history lessons tracing the island’s development from 1819, and of all the recent scholarship pushing the chronology back even more by another five hundred years. This debate over years (50 or 700?) underscores the delicate tension between the objective historical understanding of Singapore’s past, and the utilitarian value of “history” for nation-building purposes. However, it is clear that within that long time-frame, Singapore functioned as an active, dynamic and profitable trading port with a burgeoning, settled population since the early 1820s. She quickly became, after her acquisition by the British East India Company, what one visitor remarked in 1832, “the most thriving colony which the British have in the East Indies.” The historian C.M. Turnbull’s studied evaluation was that Singapore soon became “one of the most vital commercial keypoints of the British Empire.” This little book advances the simple notion that what took place before 1965 was as important as what occurred after. This is not to merely adopt another Anglo-centric view of Singapore’s history, for today’s Singapore owes so much to so many early hardy pioneers from innumerable lands. At any rate, British administration could hardly be maintained without the willing participation of some or even many “natives.” But even as scholars and historians continue to ask how old Singapore really is, it is worth the while to be reminded that the island will soon commemorate the bicentennial of the arrival of Sir Stamford Raffles in 1819. And so much of the colonial era, which his coming ushered in, still remains evident in Singapore today.

|

|

STIFLING HISTORY: There was a Singapore before 1965!

|

|

2015 was the SG50 year, and Singaporeans had much reason to commemorate this very important and significant jubilee milestone. Indeed, Singapore has come a very long way in the five decades of independence. Its stunning progress has been variously described as one from “mudflats to metropolis” and third-world back-water to city; her spectacular rise since 1965 has been hailed as a model of rapid, efficient and visionary nation-building.

It is widely acknowledged that the explosive growth of the island Republic was due to the good governance of the ruling party, and the forceful leadership of one man, Mr Lee Kuan Yew. That the first Prime Minister of Singapore was not present at the National Day celebrations in August 2015 was both poignant and poetic. The public outpouring of tribute, gratitude and honour was overwhelming and even unexpectedly massive. It demonstrated that the people of Singapore are thankful for so remarkable a leader.

However, it may be timely now to express a cautionary note. If the vibrant and independent nation of Singapore since 1965 is what it is today because of one man’s vision, then we must readily acknowledge that the very existence of modern Singapore is due largely to the efforts and activities of innumerable others, and especially the determination of Sir Stamford Raffles. In fact, the CEO of the National Library Board of Singapore, Elaine Ng, has only just reiterated, in the latest of a seeming unending stream of books on him, that “Sir Stamford Raffles, the founder of modern Singapore, is one of the most significant figures in our history.”1

Mr Lee Kuan Yew’s passing away in March 2015 marks the end of an era, when the first cohort of political leaders in post-colonial Singapore embarked on a remarkable five decades of nation-building. It is up to the current cohort of leaders to carry the nation through into the 21st century globalised world. In the wave of nationalistic pride and gush of patriotic sentiment that marked the people of Singapore in March and August 2015, it is easy to forget that the infrastructure of this lively and energetic metropolis was constructed so efficiently on a foundation that had been laid in British colonial times.

It is the duty of historians to write objective history. When applied to the reviewing of a nation’s past, this obligation often comes into tension with another important agenda, that of nation-building. When resorting to “history” so as to promote a present sense of national pride, there is the tendency to be selective about which events to recount and emphasise, which “heroes” to honour and which tragedies to relive, in order that the people not repeat those very same mistakes. Several historians have recently sounded the warning regarding too myopic a view of Singapore history,2 often written out by key stakeholders themselves.

Such a utility of history – or even “abuse of history” (a term used by the historian Margaret MacMillan3) - may have been well-meaning and seemingly innocuous, but none the less, the historian finds himself or herself at odds with the nation builder. For example, out of nearly two hundred years of existence as a trading port, colony and nation, why choose to commemorate the Fall of Singapore (15 February 1942), the Racial Riots (21 July 1964) in addition to the day of Independence (9 August 1965) above all other events? Of course, it will be argued that almost all countries indulge in the same preoccupation. Hence, the Battle of Britain for the United Kingdom, the War of Independence for the Americans, the Fall of the Bastille for the French and the stand at Masada for Israel. However these simply prove the point that, in attempting to nurture a sense of nationhood, governments and leaders all too easily misuse history.

The idea for this little booklet was first conceived in the years 2013-2014 when I taught local Singapore history to my lower secondary students in a government school. The textbook, Singapore: From Settlement to Nation, pre-1819-1971, divided itself into 10 neat chapters, with Chapter 1 focussing on pre-1819 Singapore, Chapters 2 – 5 on colonial Singapore before the Japanese Occupation and Chapter 6 on World War Two. A further two chapters delved into the movement towards Self-Government in 1959, Merger with Malaysia in 1963 and eventual Independence in 1965. The final two chapters explored the themes of nation-building in independent Singapore.4

I thoroughly enjoyed teaching this course. I felt that there was a balance in its presentation of chronology, appropriately objective without indulging in anti-colonial rhetoric or ultra-nationalistic jingoism. Enough coverage was given to the British era and the underlying sense of gratitude to the early pioneers of Singapore, whatever their ethnic group, was perceptible.

To my delight, my history students were very enthusiastic about the course content and had very little qualms about attributing modern Singapore’s success to both her post-1965 leaders and the British colonial government. In fact, I discovered any anti-colonial anti-European sentiments to be absent. This made me even more reflective, and I took time to ponder the relative objectivity with which the young approach the past. It also made me acutely aware of the history teacher’s tremendous responsibility to nurture that appreciation without exploiting it for personal or national agendas.

The history syllabus and textbook changed in 2014.5 It is now divided into four major units. Now, one whole unit is devoted to Singapore before colonial times; this, I suppose, is a response to the clarion calls for a “long duration” view of history. The colonial era has been somewhat condensed into one unit, and the final two units bring students through the war and occupation years to the period of nation-building. With the passing of time and the crossing into the landmark SG50 jubilee year, this development in school-history historiography is understandable.

Never the less, one basic premise remains even as we survey quickly the history of Singapore. That is that when independence was thrust so hurriedly onto her, she was not as ill-prepared as has been made out to be. Singapore in 1965 was not a sleepy backwater town by the standards of the day. Let us pause to re-examine the famous and oft-quoted words of Mr Lee himself, when he stated categorically, in September 1965, barely a month after Separation from Malaysia:

Here we make the model multiracial society. This is not a country that belongs to any single community - it belongs to all of us…. Over one hundred years ago, this was a mudflat, a swamp. Today, this is a modern city. Ten years from now, this will be a metropolis – never fear!6

This is the text from which many today cull the catch phrase “from mudflat to metropolis.” What Mr Lee actually said was that, “Over one hundred years ago, this was a mudflat.” That is to say, in the 1860s. And he followed up with the words: “Today, [ie. 1965] this is a modern city.” This was a reasoned, generous, if somewhat tacit acknowledgment of all that had developed under colonial administration. This progress from the nineteenth to the mid Twentieth Century is borne out in history, and this progress was subsequently carried on in the independent Republic.

|

|

AN APPEAL TO HISTORY TEACHERS IN SINGAPORE:

Who writes The Singapore Story?

|

|

I am convinced that every history teacher ought first and foremost to function as a historian. Every time we face our students, we ought to avoid simply trotting out “the facts” of history as given in the pages of “The Textbook.” As historians, our access to all manner of primary and secondary sources (often available online) is tremendous. Even in the process of imparting “historical” facts, information and data, we should be interacting with primary sources, examining the relevant issues involved, evaluating factors afresh and seeking to explain one’s own personalised “version” of – what happened. When we thus approach the great events of history – revolutions, wars, tragedies, victories and achievements – there will always be a certain curious freshness to it all, as we query assumptions and seek to reconstruct stories.

To achieve this, it is also imperative to accept that there is no one, sacrosanct, view of historical events. Historical knowledge, argues the historian John Lukacs, is necessarily revisionist. There are gaps of historical knowledge that are, or ought to be, filled; but even that filling can never be permanent. Historical revisionism is simply the act of critically and carefully examining sources with a view of improving or correcting prevailing understandings.7

The task of the Singapore history teacher to act “critically and carefully” with a view to improving “prevailing understandings” may at times be quite daunting, because of the spectacular success in which nation-builders have conscripted “the past” for their own well-meaning purposes. Few people will remain unmoved at the stirring spectacle choreographed every August during the National Day parades, when invariably, scenes from Singapore’s past are dramatized to such good effect. In playing out “the past” literally before the eyes of the nation’s citizens, few can contain the pervasive sense of pride in being “a part of history.”

Not so long ago, it was boldly proclaimed by Tom Holt that – “We are all historians.” And so, those very happy spectators at each National Day Parade were all, in effect, historians, right there in their seats as their hearts responded to the pageantry unfolding in front of them.

History, after all, is past human experience recollected. Thus our own everyday experience is the substance of history …. To construct coherent stories about this collective experience – something we all do – is to create histories.8

Furthermore, the exuberant and joyous Jubilee celebrations of 2015, while understandable, also have had the effect of entrenching the year (1965), the event (Independence from Malaysia) and the people (the “Pioneer Generation”) in everyone’s minds at the expense of all other significant years, events or pioneers. This is unfortunate, but it does underline the delicate nature of utilising history for nation-building purposes.

In the process of fixing such events in our collective psyche for the purpose of inculcating common national values, there is always the danger of creating an imbalanced view of the past. As Margaret MacMillan explains:

The histories that fed and still feed into nationalism draw on what already exists rather than inventing new facts. They often contain much that is true, but they are slanted to confirm the existence of the nation through time, and to encourage the hope that it will continue.9

MacMillan would have us all beware the dangers of slanting history, or writing “bad history,” which only tells part of complex stories:

“Bad history also makes sweeping generalizations for which there is not adequate evidence and ignores awkward facts that do not fit.”10

What then can we do with history? Well, for a start, we should seek to write and teach “good history.” We must “do our best to raise the public awareness of the past in all its richness and complexity.” MacMillan goes on to urge the historian: “We must contest the one-sided, even false, histories that are out there in the public domain.”11 At the very least, we need to ask the simple question: just when did Singapore “begin”? Was it 1965? Or was it earlier? If the latter, then how much earlier?

We do well to heed MacMillan’s cautionary note when we survey the common, almost daily usage of (what scholars have dubbed) “The Singapore Story”12 in the attempt to forge a sense of national identity, particularly in the local schools. This “Singapore Story” refers to the quasi-official version of Singapore’s history which dominated from the 1990s. As historian Karl Hack explains:

From 1998, the “Singapore Story” was entrenched. First, there was the major public exhibition on the “Singapore Story,” emphasising the war years, the subsequent PAP struggle for independence and against communism, ethnic chauvinism and economic peril. Second, “National Education,” based around this narrative – and attached “lessons” about how Singaporeans must behave – was integrated into school curriculums, at first as separate lessons, and ultimately infused across subjects. Students were also taken on “Learning Journeys” to wartime and business sites to reinforce the story’s messages. There was an insistent state desire that students at all levels be imparted lessons through social studies at Primary School, and history at Secondary, such as “We Must Ourselves Defend Singapore.” There was also relentless emphasis on the need for social and economic discipline.13

There was an urgent political utility to this yoking of history for the cause of nation-building. For Singapore’s leaders “to function in the world system of nation-states, they needed to shape and disseminate a sense of national identity which privileges political identification at the level of the nation state.” The writing of the nation’s history thus became of great importance to those who sought to lead it.

The history that the state tells of itself, and the degree of its success in getting its citizens to embrace that history as their own, are thus central to the process of is nation-building.14

We are now also warned by no less an authority as the historian Sam Wineburg, that simply recollecting past experiences, even collectively (such as happens every day in the schools, annually on 9th August or once every fifty years) is not true historical thinking. Neither is the normal, innate human yearning to connect to traditions and stories that have brought us to the present. Wineburg’s tantalising proposition is that historical thinking is actually quite unnatural. It “requires an orientation to the past informed by disciplinary canons of evidence and rules of argument.” It seeks the verification of sources and questions mere stories. Wineburg asserts that the discipline of historical thinking involves:

...interrogating sources, putting them on the stand and demanding that they yield their truths or falsehoods...15

It is with this spirit of thinking objectively, founded on empirical evidence, the history teacher must embark on truly “teaching history” so that generations of young people will know more than just the specially selected milestone events of the nation’s past. What this also means for Singapore is that historians will continue to examine and re-examine her past from a gamut of angles. Based on newly surfacing historical evidence, they will revise it, if necessary, and propose different points of view from which to write the narrative.

Let us therefore, in the classrooms, endeavour to ensure that “The Singapore Story” is as long as possible – in time scope; as broad as possible – including many protagonists, and as honest as possible – acknowledging many viewpoints for complex issues.

For an in-depth discussion on the social roles Singapore teachers are expected to assume and how they grapple with the twin demands of having to exhort students to think creatively but within certain nationally prescribed boundaries, please refer to Loh Kah Seng and Junaidah Jaffar, “Academic controversy and Singapore history.” Ivy Maria Lim also writes about the importance of teaching historical controversies in Singapore, but points out that these “do not find a place in textbooks.” Furthermore, the very educational experiences of teachers themselves at times debilitate their own efforts at structuring academic controversy in class. See her “Teaching historical controversies using the Structured Academic approach.” Both articles are in the book Controversial History Education in Asian Contexts, edited by Baildon, Loh, Lim, Inanc and Jaffar. Details are in the Bibliography.

|

|

THE BRITISH EMPIRE AND COLONIAL CITIES

|

|

In his controversial book, Ten Cities that made an Empire, Tristram Hunt points out an awkward paradox that has emerged in the study of the British Empire. That is, while the legacy of Empire moves into the realm of official apologies, law suits and compensation settlements, certain phenomenon still persist. One of these persistent phenomena is the continued existence of former colonial cities dotted around the globe.

From the Palladian glories of Leinster House in Dublin to the Ruskinian fantasia of the Victoria Terminus in Mumbai to the stucco companile of Melbourne’s Government House to the harbour of Hong Kong, the footprints of the old British Empire remain wilfully in existence.

Hunt observes that this imperial heritage is now being preserved and restored “at a remarkable rate as postcolonial nations engage in a frequently more sophisticated conversation about the virtues and vices, the legacies and burdens of the British past and how they should relate to it today.”16

This striking, if somewhat uncomfortable, phenomena is very evident in Singapore today. If by “colonial” we simply mean the period before the 1960s, then innumerable “colonial” buildings, structures, edifices, monuments and institutions abound in Singapore. At the present time, the Urban Renewal Authority and the National Heritage Board are conscientiously conserving or preserving many historically or architecturally significant buildings, a great number of which stand in older, “colonial” estates beyond the core city centre – in Tiong Bahru, Chinatown, Kampong Glam, Katong, Geylang, Joo Chiat, Queenstown, Alexandra areas and more. Even if one were to confine the observation to European-style or influenced buildings within the “civic district” serving the administrative, judicial, social, religious and recreational purposes of the British Empire, the list is very long:

- The Armenian Church, St Andrew’s Cathedral, Convent of the Holy Infant Jesus (CHIJMES), the Supreme Court building, City Hall, Empress Place (Asian Civilisations Museum), the old Parliament House, Victoria Theatre and Memorial Hall, Fullerton Building (now Hotel), Hill Street Building, Central Fire Station, Singapore Musuem, the (Philatelic Museum), the ……. (Peranakan Museum), Raffles Hotel, Singapore Cricket Club, Singapore Recreation Club, to list the more obvious ones.17

A prime example of how the authorities have effectively retained and revitalised older, historically significant buildings for contemporary use is the brand new National Gallery Singapore. This latest masterpiece occupies two national monuments: the former Supreme Court and City Hall. The official Gallery website describes the two iconic buildings as “landmarks of Singapore’s colonial past and journey to independence,” which have “borne witness to many pivotal events in the nation’s history.”18

And it is not just these two splendid architectural treasures. Many grand and very much revered buildings are not only in no danger of being demolished for anti-colonial, ultra-nationalistic (“let’s be rid of our colonial past”) reasons, but are being voraciously preserved for future generations. The old street names of Singapore roads, many of which date back into the Nineteenth Century, and include British names, stand in testimony of a bygone era which we have come to accept for all its “good” and “bad.”19

And perhaps it’s just that we have come to recognise that the past is not so easily judged in the most simplistic terms of “good” and “bad” that has made it possible to incorporate elements of our collective, even colonial, past into the modern Singaporean psyche.

Indeed, the historian John Darwin has described Empire as “not just a story of domination and subjection but something more complicated: the creation of novel or hybrid societies in which notions of governance, economic assumptions, religious values and morals, ideas about property, and conceptions of justice, conflicted and mingled, to be reinvented, refashioned, tried out or abandoned.”20

This might explain the pragmatic approach taken by Singapore to keep and adapt many aspects of the colonial past. This practice tacitly recognises the solid foundations the Empire provided but also allows the present generation to skilfully review, revise, modify and improve on them so that ancient institutions, practices and traditions remain relevant and useful today. Singapore’s parliamentary system, judiciary and legal system, military organisation, education system, civil service and economic system all bear out the same imprint of Empire and yet most of these original institutions have been heavily “localised” and made relevant to the Republic’s current needs.

|

|

COLONIAL AND MODERN SINGAPORE

|

|

The nation’s jubilee celebration of Singapore’s success as an independent Republic was not only a campaign marked by emotional and sentimental patriotism. There was, and is, a clearly enthusiastic effort by the academic and scholarly community to chart, chronicle and document many aspects of this success. Earlier in 2015, the reputable World Scientific publishing company launched a 25-volume book series to commemorate Singapore’s 50 years of nation-building. The series sought “to bring readers through an informative reading journey on the challenging paths that the Singapore pioneers have so boldly charted.”21

The World Scientific definition of “pioneers” is aligned to the recently-made-popular usage, referring commonly to those residents of Singapore who were already young adults when nationhood was attained in 1965. Clearly this meaning of the term “pioneers,” when unceremoniously imposed on the population at large in the months leading up to the Jubilee year, as part of a whole slew of privileges granted to those newly-defined as “the pioneer generation,” disregarded the very long-standing historical utility of the term itself.

For a long time, everyone thought of Tan Tock Seng, Govindasamy Pillay, Whampoa, Eunos bin Abdullah et al as “pioneers” of Singapore. Suddenly, overnight, people of my parent’s generation became the true pioneers. Certainly, that generation of the 1960s did play a large part in the nation’s story, however, even they were surprised to be conferred the title of “Pioneer Generation” so instantly. Of course, the numerous privileges now accorded to them quickly overcame any nascent queries as to the scholarly validity of the new terminology.

It must be said, happily, that there is a symmetrical balance in looking back on the recent past as part of the Jubilee celebrations. The intelligentsia of Singapore have indeed adopted a generous and encompassing view of Singapore’s history. It is one that does not simply begin with 1965, but extends the story backwards to the time even before Raffles.

Not to be outdone, and to provide just that weighted balance needed, the Institute of Policy Studies in December 2015 launched the first few books of the fifty-volume Singapore Chronicles. This ambitious series, according to the Director Jenadas Devan, “provides succinct introductions to various aspects of Singapore.” Its diversity in subjects is very impressive indeed, ranging from “the fundamental to the practical, the philosophical to the mundane.” The series is a very serious enterprise, not to be taken lightly. To prove this point, the books are “written by experts for the intelligent reader” and aim to capture “the story of our island-nation.” The fifty volumes, when fully launched by mid-2016, will focus on “the milestones of our history – from pre-colonial Singapore to our separation from Malaysia.”22

It is very significant that Volume 1 of the whole series is Colonial Singapore, written by that most respected and admired of historians Nicholas Tarling, no less. The descriptive paragraph on the back of this book very clearly and unabashedly sums up the intent of this book, and is crucial to the thesis of this essay. I quote it in full – words underlined are mine for emphasis:

This book is a history of Singapore from the founding of a settlement by Raffles in 1819, to the post-imperial phase inaugurated by World War II and the Japanese invasion. It shows how colonial Singapore matured as an economy and developed as a society even as it grew into a commercial centre that was also a centre for the movement of people and ideas. The book captures the essence of the island-city’s place in the Asian economic and political scheme of things as European imperialism reached its zenith before giving way to Japan’s military advance. The fall of Singapore to the Japanese in February 1942 embodied the new times. The return of the British after the Japanese defeat in 1945 set the stage for a fresh phase of Singapore’s political development as the anti-colonial movement grew in strength.23

This essay proposes the simple argument that the foundations of modern Singapore were laid out in colonial times. The massive infrastructure has been built up in the era of post-1965 nation building. However, for a long time, even now, the colonial legacy remains evident. In many ways, it continues to provide the ideological, architectural, systemic and administrative pattern for life in Singapore today.

Professor Tarling himself writes of this superbly situated small island but maintains that its success was never only due to geographical positioning. Singapore, instead, is the “creation of many people.” These people (the real “pioneer generation”?) came from many lands, as settlers and sojourners. Tarling argues that what Singapore is today is due both to their own efforts, as well as “on the decisions of outsiders, colonial and post-colonial, and their handling of them.”

This short book aims to describe the trajectory its history took as a result, from the siting of a small settlement by the British East India Company in 1819 to the emergence of an independent Republic in 1965.24

In order for economies to prosper, there must be law and order, deriving from good governance. The rapid construction of political and judicial institutions paved the way for businessmen, traders, merchants and prospectors to venture in with confidence. The greater the prospects for individual and collective financial success were, the greater the draw for other immigrants to come in from afar. And Singapore in the Nineteenth Century was a magnet for many people from many lands to arrive in search of better fortunes.

|

|

WHAT SINGAPORE WAS NOT

|

|

Singapore was founded by the British in 1819. So we were all taught in school. Generally speaking, this is factually correct, but of course, the assertion begs clarification and explanation. For example, it was not really the “British” or even the “English” who founded the colony, but the Honourable East India Company, that ancient and venerable institution devoted to business and trade. With the royal charter, it had liberty and license to travel the world for commerce, business and profit. Invariably, good trade required local conditions of peace and stability, hence the many instances of flag following the trade.

It wasn’t even the whole island that the EIC acquired in 1819, but really just the area around the mouth of the Singapore River, for the purposes of establishing a trading settlement. It would have been too impulsive to have had taken the whole island and be saddled with a burden too big to bear. It was only in 1824, after five good and profitable years, that the Resident John Crawfurd sealed a deal with the Sultan, acquiring the whole island of Singapore. By then, the colony had proven its worth, business was excellent, and immigrants were pouring in from all over the world.

It wasn’t even only Thomas Stamford Bingley Raffles who was responsible for the founding of the new settlement, though one would argue that he played the large and vociferous part. An ongoing academic debate has seen other good men put forward as instrumental in the acquisition and establishment of Singapore, William Farquhar and John Crawfurd, both Scottish men, being the most prominent.25 Indeed, Farquhar was on the boat that brought Raffles to shore in late January, and whom Raffles installed as the first Resident on the colony, and whose foresight and activity saw the colony fitted out with public buildings, paved roads, a harbour and port and a rudimentary police force.26 But other European communities played foundational roles as well. One mustn’t neglect to mention the Irish, the intrepid architect of early Singapore, George Coleman being among the most well-known. His public buildings still stand today, testament to his vision and enterprise. And who would have thought of the French who were there in the fray as well, doing good for the settlement.27 We must also mention that the historian John Bastin has put together a landmark collection of correspondences between Raffles and his superior in the EIC, the Marquess of Hastings, then Governor-General of India, demonstrating the major role played by the latter in Singapore’s founding, a fact thus far much overlooked.28

To highlight the contributions of the various European peoples to Singapore’s genesis and growth is not to denigrate the incalculable amount of labour, much of it back-breaking, put in by the Asian immigrant and settler communities in order to build the colony and, later, the nation. Witness not just the literature written to record their deeds and activity, such as the excellent “peoples’ history” by James Warren on the rickshaw-coolies and by Stephen Dobbs on the occupations and lives around the Singapore River29 but the number of new and older museums now established to archive their lives and educate the present generation of the monumental part played by their forefathers.30

However, while we must acknowledge the part of Farquhar, Coleman and the numerous Asian immigrants in building up the colony, we remain persuaded that it was Raffles who harboured the ambition to obtain some kind of trading port for British trade somewhere in the Malay world. It was Raffles who therefore set in motion the whole process of diplomacy and search for a new port of call.

It wasn’t Singapore, to begin with, that Raffles had hoped for. It was really the Riau islands, and that after Raffles himself had witnessed the inadequacies of Penang and Malacca. As it turned out, the Riau islands had been occupied by the Dutch, and left with diminishing options, Raffles headed north for the ancient island of Temasek, or Singapore.

It wasn’t even only for the China trade, although that has been the predominant historical reason given for the founding of Singapore. Singapore did lie on the tea trade route that linked Europe to India and to China, from whence the tea came. But Singapore was not so much obtained for Chinese reasons, as for Indian reasons. The question specifically of tea was not a major one in 1819. It was the influx of Chinese sinkheh (newcomers) into the island after the founding by the British that has bedazzled us all into assuming that the China tea-trade reason prevails. But the lucrative tea trade and the flood of Chinese would really only come after Raffles, and not before. Prior to 1819, the main thrust of policy was to find a port to serve as an outlying naval base for the British navy patrolling the Indian Ocean. The British had hoped Penang would be that naval base, but she was too exposed to the elements. Malacca, also British by then, had waters too shallow. Singapore, with her excellent deep harbour, turned out to be more suited. The island was located at the southern end of the busy Straits of Malacca, which was then not so much a passage to China as it was a passage from India.31

Finally, Singapore wasn’t even conquered. There was no bloody takeover, no fighting the natives, no battle, not even a skirmish or as much as a scuffle before Raffles could wrest control of the island for the Company. Instead, there was just a treaty signed and the island handed over in exchange for a tidy sum of money. It was, in all likelihood, it must be said, an unequal treaty. However, because it was a peaceful transaction, and because the vast majority of Singaporeans today descend from those immigrants who flocked in after 1819, and not before, we islanders do not suffer from any “victim” mentality. A good number of other ex-colonies do, and still struggle with building an identity detached from colonial rule. Singapore, in contrast, even with SG50 somewhat obscuring our clear vision, has had fewer difficulties with her colonial past. English is retained as the main language, English street names persist everywhere, grand colonial edifices remain in use, and in fact, are often renovated and made even more glorious in bearing. Institutions today abound which had their foundations in colonial times; and, quite remarkably, Singapore school students still sit for the General Cambridge Certificate Ordinary and Advanced Level Examinations.

|

|

STRETCHING HISTORY:

The “Long Duration” View of Singapore

|

|

In 2004, the Singapore History Museum published a book, Early Singapore 1300s – 1819: Evidence in Maps, text and Artefacts, and put forth “a convincing case for a 700 year-history of Singapore.”32 There are strong reasons advanced for casting the history of the island further back in time, all the way to the 1300s. Derek Heng has argued that if pre-colonial Singapore’s past is to become a relevant aspect of its social memory and historical narrative, then there is a need to consider the island’s history even beyond the time of its being a regional or global city to one that is indigenous.33

The National Archives of Singapore joined in the fresh discourse and in 2009, sponsored another new book, Singapore: A 700-Year History, whose editors were recognised and respected members of the nation’s academia. These editors were critical of the current popular strand of “The Singapore Story” and highlighted the “moral dilemma of whether propagation of The Singapore Story to promote civic virtues is an appropriate use, or misuse, of history.”34 Their own response to the whole issue was to relook Singapore’s history and cast it far back in time, and proposed a “long duration” view of the nation’s story.

Our rich current knowledge of pre-1819 Singapore has been derived from a wide range of evidence drawn from artefacts and archaeological data, traditional Malay literatures, early Dutch and Portuguese sources, as well as Chinese accounts. The resultant wave of scholarly works, have to a good extent, reinstated the days of ancient pre-British Singapore. Archaeological excavations and findings have abounded in recent years, yielding a wealth of material, artefacts and clues which have helped us reconstruct something of the island’s lengthened past before 1819. It has been established that even if Singapore was a “sleepy port” when Raffles set foot here, it was only because she had become one, and not that she had always been one.

As early as the thirteenth century, Singapore, or Temasek, had risen as an emporium serving the South Johor-Riau Archipelago economic area, with trading links to major Asian economies at Java, the Indian Ocean and China.35 The archaeologist John Miksic has argued persuasively that by the fourteenth century, there was even a settled population of Chinese in Southeast Asia, including Singapore, with very close links to China. In addition to economic activity round the Singapore River, Miksic even speculates, quite tantalisingly, that the Peranakan culture – “mixing Malay, Chinese and other crafts and objects into a distinct Straits blend” – might have roots as far back as this era.36

Old Temasek was indeed a vibrant, lively and prosperous maritime-based centre of trade in the region, within the geo-political structures provided by the Johor-Malacca Sultanates. That much we must acknowledge and teach our students, which we now do. However, the advocacy of any “long-duration” view of Singapore must consider this: ancient Singapore did not survive much. Due to a variety of reasons, her prosperity eventually declined and her reputation faltered, long before the EIC flag was raised at the River mouth.

Temasek’s role as a regional port-city lasted more than a hundred years, with several external factors causing her demise. By the fifteenth century, she was overtaken by Malacca, and for the subsequent three centuries remained a minor port in the Straits of Malacca, “relegated to the role of secondary port, servicing first Melaka… and then Johor in the sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries.” It was:

Not until 1819, when Stamford Thomas Raffles established a factory in Singapore on behalf of the English East India Company, that Singapore emerged once again as an autonomous port-settlement, and was engaged once again with the international maritime economy.37

On the other hand, the evidences of colonial Singapore not only have so far endured but have, in some ways, even flourished since 1965. In addition to keeping the English language and parliamentary democracy, there still is National Service, a very British institution. The British tried to introduce it in 1955, but the Chinese schoolboys protested. Today, all their grandsons quietly board the transports for Pulau Tekong, a national rite of passage. It might even be argued that many values which formed the bulwark of the imperial system have been whole-heartedly retained today: judicial integrity, administrative impartiality, transparency, law and order and sportsmanship.

|

|

WHAT SINGAPORE BECAME:

A Thriving Colony

|

|

Under the benevolent rule of the British administration, first as part of the Straits Settlements governed from India and then later as a Crown Colony, Singapore’s population, economy and reputation grew by leaps and bounds. From all over the world, people made their way to this little gem at the southern tip of the Malay Peninsula. Drawn by the prospect of fortune and assured of a relatively safe existence by the presence of British military and civil forces, men arrived in droves, and each contributed his part towards the story of Singapore. As early as in 1832, barely thirteen years after her founding, traveller Benjamin Morrell described with excitement the burgeoning town:

For the short period it has been in existence, Singapore is, without an exception, the most thriving colony which the British have in the East Indies; being admirably situated for all the purposes of trade, and is in fact, a centre depot for the commerce of the Chinese and Javanese seas.

All manner of goods, food and products could be found in Singapore. Among the more sought after items included tortoise shells, pearls, gold-dust, edible birds’ nests, birds of paradise, minerals, shells, pepper, coffee, sugar, hemp, indigo, gums and drugs, and precious woods. It was therefore no surprise that “within the last ten years, this place has increased and flourished beyond all calculation…to a splendid well-built little city.”38

Colonial rule provided the necessary structure and framework within which Singapore swiftly became prosperous. The new colony soon thrived with business and trade. John Turnbull Thomson, arriving by ship in Singapore in 1838 at the start of a lengthy tour of the Malay world, was delighted to hear the shout – “Singapore ahoy!” Before long, he was “anchored in British waters.”39

The River throbbed with life and the rapid increase in ships, sailors and soldiers was a simple testament that the island was pulsating with wealth. The River itself was the heart and soul of colonial Singapore. Not only was it where Raffles had stepped ashore in 1819, but by 1860, the very life of the city was to be found here. Its narrow waterway teemed with all manner of boats, junks and vessels, each bringing in the goods of the world from the larger ships anchored out on the coasts of Singapore. On both sides lining the River, trading houses, warehouses, banks and a whole variety of services kept the economy of the colony going. The merchants had their offices at nearby Boat Quay and Commercial Square, where crowds would gather each day to exchange business news and listen to travellers’ tales.

The ships kept sailing into Singapore, tribute to her robust growth as a trading port. In 1856, over half a million ships had arrived; the value of the island’s commerce by this time doubling what it had been fifteen years before. Clearly, trade was Singapore’s lifeline and the British brand of free trade was proving to be a success. Merchants who plied their wares in other ports gravitated to Singapore, and she quickly became the crucial hinge between trade in the Indian Ocean, the South China Sea and the Java Sea.40

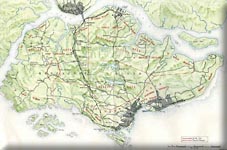

The first and second British Residents, William Farquhar and John Crawfurd laid the foundations for the swift progress. Within a few years, the roads were laid out, public buildings erected in the usual orderly fashion of Empire, a rudimentary but sufficient system of law and order prevailed, and the colony was set to go. A quick glance at the famous map of Singapore in 1823 as sketched by Lt Jackson certainly demonstrates the typical neat and business-like lay out of the settlement, from Chinatown, north of the River, to the Arab Quarters, south of the River. The races were kept apart, according to the prevailing notions of people management in the Nineteenth Century. The British appointed Kapitans, and worked with them, as they in turn maintained order among their own ethnic groups, or clans. In this way, the authorities could keep an eye on local matters without having to intervene high-handedly too quickly.

What the new colony also needed in large quantities and rapidly, were workers. These came in great numbers, and as a result, the population of Singapore burgeoned, from some 150 orang laut in 1819 to 30,000 just twenty years later. Almost half of these were Chinese from China. The reasons for migration have often been categorised simply into the “push” and “pull” factors. The former reasons are easy enough – natural disasters, civil war, lack of jobs et cetera. What pulled them specifically to Singapore is a rather more intricate question, but significant for our purposes. While family or clan relations did play a part, quite certainly, there were more distinct factors that drew the many here.

The possibility, and the perceived probability of economic wealth, combined with the reputation of the British for upholding suitable conditions amenable for business soon lured thousands upon thousands of young men onto the shores of sunny Singapore. The myriads of men arrived from all over the world – from places associated with the British Empire, which Singapore was part of now, as well as places outside the British Empire, such as China. This combination was remarkable, and demonstrated both the liberality of colonial administration as well as the adaptability of the expanding population of the island. Even in the 1830s and 1840s, almost everyone walking the streets of Singapore had not been born here. But having spent more and more time on the island, and the temptation to return “home” diminishing, the many men and few women of Singapore became resigned to the convenience of simply living here, hopefully making it big here, and quite likely, dying here. In other words, many had come to reckon Singapore to be their place of residence, if not home.

The colony rapidly defined itself by becoming multi-racial, multi-cultural, multi-lingual and multi-religious. Thomson’s observation of the inhabitants in the pulsating colony, is well worth quoting:

Here is a conglomeration of all eastern and western nations. Subjects of nations at war are friendly here, they are bound hand and foot by the absorbing interests of commerce. The pork-hating Jew of Persia embraces the pork-loving Chinese of Chinchew. The cow-adoring Hindoo of Benares hugs the cow-slaying Arab of Juddah. Even the Englishman, proud yet jolly, finds it to his interest to unbend and associate with the sons of Shem, whether it be in commerce, in sports or at the banquet.41

History books are replete with examples of how these new immigrants lived difficult lives in Singapore, how many made their names or filled their purses, and how each in their own way contributed to building up Singapore. There was specialisation too: the Chinese as planters, traders, businessmen, coolies, rickshaw pullers and labourers. The Indians worked in finance, money lending, laundry and managed general sundry stores. Many came as convict labour and numerous too by way of the British Army. The Malays worked hard as policemen, fishermen, gardeners and in the sea-related vocations.

Singapore was indeed a typical British colony. Its multitudes of people remained largely separate one from another both by choice as well as by design. It was a plural society, where the different ethnic groups lived and worked within their own community, keeping an arm’s length from other groups. It was not just that the European colonial society existed apart from the larger Asian masses, but even the Asian mass was never a homogenous group. We today are uncomfortable with ethnic quarters or ghettos, but it was the norm in the Nineteenth Century, all over the world. Social relations between the races were endemically laced with mutual suspicion, without always degenerating into armed conflict. Chinese clerks in the local law courts would surreptitiously refer to the “red devils” in their documents, just as the Manchus in China labelled their foreign visitors as barbarians. The Europeans did not expect to be invited to the clubs of the Asian community, but neither did the locals expect to be welcome into the sports clubs of the colonial society. Not yet, at any rate.

|

|

A “VITAL COMMERCIAL KEYPOINT” OF THE BRITISH EMPIRE

|

|

The diverse, varied and transient population proved no hindrance whatsoever to the swift rise of the colony. In 1867, the administering of the Straits Settlements – Penang, Malacca and Singapore – passed over from the East India Company directly to the Crown. This had occurred partly because of the growing financial difficulties faced by the East India Company and partly because the British government back home had come to value Singapore as a naval base for its ships. This transfer to the Colonial Office meant that from henceforth even more attention would be paid to the Straits Settlements. Singapore ceased to be an isolated settlement, “looking out to sea, living on her nerves and her wits in the uncertainties of international trade.” Her role in the region and the Empire would now take on even more greater proportions:

She acquired permanent status as a major entrepot on the leading East-West Straits of Malacca trade route, the focus of the trading wealth of the Malay peninsula and the Dutch East Indies, and one of the most vital commercial keypoints of the British Empire.42

When the Suez Canal opened in 1869, providing a long-awaited water-route through the deserts of Egypt and reducing the time taken for all sea travel to the East by a great deal, shipping to and trading with Singapore grew significantly. This, coupled with the latest developments in steam navigation, meant that the new Suez route gained popularity. The steam engines and clippers still required frequent replenishing of coal and fresh water between Europe and China, and this gave rise to the need for well-placed coaling stations. Singapore inevitably became another such coaling depot, thus acquiring a new strategic and economic significance in the global trade network. “It was Singapore’s singular good fortune to lie on the natural routes of both sailing and steam vessels.”43

The whole settlement rapidly transformed into an ever growing boisterous place and a heavily populated colonial port-city. In the 1840s, not long after Morrell’s report, her population still only numbered in the low tens of thousands. By 1871, this figure had mushroomed to 97,000 inhabitants, the vast majority of whom lived within or just beyond the town limits.

There were several effects of this sharp population growth. For one, the pressure forced the town of Singapore to spread out: to the west toward New Harbour (later Keppel Harbour), to the east toward Geylang and Katong along the East Coast Road; to the northwest, along River Valley Road and Orchard Road toward Tanglin; and to the north along Serangoon Road toward the far end of the island. Second, the port city that quickly emerged through this multitude of people was both “gentrified and dilapidated, prosperous and poor – European and Asian.”44

|

|

THE PROBLEM WITH IMMIGRANTS

|

|

However, with people came problems. Within a matter of decades, Singapore also became rather difficult to manage. As the numbers of people working here exploded out of hand, the tiny police force struggled to keep order. This was a critical issue because for any economic development to be realised, there had to be governance that upheld and enforced law and order. Perhaps one reason why the police force was so quickly overwhelmed was the nature in which the immigrants congregated.

It was quite natural for new immigrants to be drawn to those of their own community, especially if those ties of kinship or dialect group extended back to the original homelands. The Chinese sinkheh who arrived stepped into the comfort and security of his community. Secret societies, or triads, were prevalent everywhere, established initially to provide new arrivals with friendship, accommodation and assistance in finding jobs. These societies, however, also had a shady aspect, with dealings in money-lending, gambling dens, prostitution and the collection of protection-money. Gangsters were often recruited to ensure compliance and by the middle of the century, there were few Chinese businesses that remained out of the clutches of the secret societies. It was well known that even the big Chinese towkays, or businessmen, had either dealings with the triads or were even office-holders in them! The pervasive, far-reaching and troublesome tentacles of the Chinese secret societies posed a dilemma to the government: how to suppress the illegal and harmful activities of a community that brought in so much profit and business.

Open clashes between the gangs occurred for many reasons – over territory, membership, extortion and control of both lawful and illicit trades. In 1851, the Ghee Hin triad, regarded as Singapore’s first secret society, launched an attack against Christian Chinese-owned gambier and pepper plantations. Known as the Anti-Catholic Riots, the assault was directed at former Ghee Hin members who had eroded the society’s control over the gambier and pepper plantations when they left to join the Catholic faith. The attacks spread to all over the island, and left some 500 Chinese dead and 27 plantations destroyed, before being quelled by the British.45

Laws and ordinances were cumbersome and slow to check the growing social blights. Instead, the secret societies thrived on the increasing coolie movement as Chinese immigrants flooded into Singapore, attracted by opportunities for work in the British Malay States. By the mid-1870s, the November-February junk season brought 30,000 Chinese to Singapore annually; this number included numerous samsengs, or professional thugs lured by the demand for fighting men in the Perak tin mines. By 1872 the Singapore Ghee Hok society alone had 4,000 samsengs at its command.46

The Colonial Office viewed the mounting troubles in Singapore with some anxiety, as the numbers of riots sweeping through the colony spiked. The Coolie and Samseng Riots which broke out in 1871 after a minor pick-pocketing incident between a Hokkien and a Teochew, descended into open street battles which the police authorities struggled to suppress. In 1872, an official Commission of Enquiry outlined clearly what it felt to be the root causes of the trouble, which stemmed from the Mandarins back in China “clearing out hordes of rowdies and bad characters who have infested a district near Swatow” (in China).

Numbers of these roughs and bad characters who have escaped with their lives, have been brought to the Straits by sailing and steam vessels, and are now infesting this Colony with their presence. These men accustomed to live in their own country by plunder and violence bring with them the lawless habits they have acquired. They are attached to the various secret societies existing in the Colony, and pay implicit obedience to the orders, whatever they may be, given them by the headman.47

In view of such disturbances among and by the Chinese in Singapore, one historian has observed that beneath the surface, British rule did not have very much de facto authority. And that it was the Chinese who were the real power in Nineteenth Century Singapore. In fact, “Chinese riots were trials of strength, conducted with impunity as if the government did not exist.”48 While the government resorted to the military, the police, and the law, these were all with a mixture of results. It was later, with the appointment of Mr William Pickering as the first Protector of Chinese, that the tide began to turn.

|

|

OTHER TROUBLES

|

|

Then there was piracy, an ancient but troublesome menace to the increasing number of ships and merchants drawn to the colony. Though likely situated in the Eighteenth Century, the blockbuster-movie Pirates of the Caribbean: At World’s End, lures viewers into the dark and murky underworld of Singapore. When Captain Barbarossa alights from the ship, the pirate-gangster Sao Feng greets him with a barely-muffled hiss: “Captain Barbarossa, welcome to Singapore.” Piracy was a clear and present danger to legitimate trade. As the threat to merchandise and even life increased, traders debated the worth of navigating the Straits of Malacca and anchoring at Singapore. And since trade was the lifeline of the colony, it was imperative that the authorities do something effective and fast.

Still other problems existed and persisted as well - inter-ethnic tension and petty quarrels, the abuse of coolies, illegal smuggling and trade, street crime and the like. One ghastly scourge afflicted many Chinese immigrants: opium addiction. The drug was easily available, and was sold and consumed virtually without restraint. The habit of smoking was so pervasive that the authorities were well aware of the dens but unable and unwilling to suppress it totally. Travellers were quickly struck by its prevalence and tragic effects it had on its victims:

These haunts of the drug that enslaves were long and narrow rooms, with a central passage and a long, low platform on each side…. Ranged along on these platforms wide enough for two men, facing each other and using a common lamp, were scores of opium smokers…. One Chinese man was so far under the influence of the drug that his eyes were glazed and he was staring at some vision called up by the powerful narcotic. One old Chinese, seeing our interest in the spectacle, shook his head and said, ‘Opium very bad for Chinaman; make him poor, make him weak.’49

Opium dens proliferated, especially in the Chinatown area. In 1848, there were 45 licensed opium shops; by 1900 there were 550. The trade was so lucrative that both the colonial authorities, who monopolised the supply of raw opium, and the wealthy Chinese business men, to whom were leased the rights to prepare and distribute the opiate, reaped great profits. Consequently, the will to suppress this harmful trade was initially rather weak. Illegal gambling was another social ill. Although outlawed in 1829, enforcement was sporadic and ineffective. Punishment of offenders was light, and frequently, police officers sent to investigate the gambling dens or arrest the culprits were confronted by hired gangs of thugs.

The flood of Chinese coolies into Singapore throughout the Nineteenth Century resulted in both severe overcrowding in the Chinatown tenements as well as abuse of the coolies themselves. Largely uneducated, unskilled and poor, many coolies found themselves in labour-intensive, back-breaking work as construction workers, plantation workers, rickshaw pullers and stevedores. Often, their very existence and employment in the colony were controlled by those shady agents to whom many paid exorbitant fees in advance. One more burdensome social problem was prostitution, a not unexpected result of the disproportionate ratio of men to women on the island (1 female to 14 males in 1860). Prostitution ruined the lives of countless women and caused large-scale health issues.50

Often enough, the dark shadows of the gangs loomed over these venues of vice as well. Overwhelmingly, it was the secret societies and piracy that tested the problem-solving skills of the colonial administration. How the British authorities set about suppressing crime was a testament to their administrative ingenuity as well as technological prowess.

|

|

ENFORCING LAW AND ORDER

|

|

Thomas Dunman was appointed the island’s first Commissioner of Police in 1856. Realising how difficult it was to recruit good Chinese men into the police force where they would often have to confront their fellow-Chinese in the gangs, Dunman established the Detective Branch in 1862. This move allowed Chinese to enter the force as plain-clothes officers and work undetected by those they were trying to apprehend. The pay and working conditions of the police were improved, and consequently, morale and efficiency were also enhanced. In 1871, William Pickering, fresh from colonial duties in southern China, was posted to Singapore and in 1877, became the island’s inaugural Protector of Chinese. With the glorious title came manifold expectations, and Pickering certainly lived up to these.

Men such as Dunman and Pickering introduced a slew of new initiatives which in turn gradually gained the confidence of the local community. The delicate combination of stern measures to suppress the troublesome secret societies and more open, transparent dealings with the locals slowly won over many. The ability and willingness of Pickering to conduct his conversations in Mandarin was also a significant factor for his success, even as he prosecuted the tough stance of registering and monitoring the activities of the societies.51 However, as expected, the force and rapidity of the changes in law enforcement also incurred the wrath of many gangsters, who sought means to stem the tide. The attempted murder of Pickering in 1887 was one expression of frustration on the part of the offended.

a

English technology was crucial in giving the authorities the edge over criminals. On the high seas, piracy was dented, then checked by the advent of the steam-powered gunboat. These crafts, now cruising independent of the wind, deftly cornered many a pirate, slowly but surely wresting control of the waters away from the marine thugs. In doing so, trade and businesses were assured of greater safety, and the maritime-based economy of Singapore set on a more sure footing.

The telegraph, steam engine, finger-printing equipment and better weaponry were just several of the technological advances which gave the British sheer superiority of power over others. But it was not just technology. The administration of an Empire so vast and large, so diverse in peoples and conditions, required an educated elite force to manage it. The schools and universities of Britain churned out scores of young men ready to administer the Empire. The Victorians, it seemed, wanted their Empire ruled by the ultimate academic elite: impartial, incorruptible and omnipresent.52

In Singapore, such an efficient and well-oiled colonial administration was just what was required to keep the burgeoning population in check. Law and order was of the essence if the colony was to survive, let alone thrive. The presence of a robust police force, stern judiciary and stiff civil service all combined with the lively, highly-adaptable and hardworking inhabitants to quickly prove that the island was indeed a splendid little colony.

Although by our standards today rather inadequate and sporadic, the colonial authorities also initiated rudimentary education and health care services. One way by which the ruling elite could be assured of a middling-rank of supportive locals willing to collaborate was education. Not only were schools constructed, teachers employed (albeit mostly European to begin with), but intelligent and highly motivated young Asian men were provided with attractive scholarships to study in the best universities in England. Queen’s scholars such as Song Ong Siang, later “Sir,” quickly formed part of a loyal bureaucracy as lawyers, and civil servants. English-styled education in local schools such as the Anglo-Chinese School, Raffles Institution and St Andrew’s School turned out little Anglo-Asian boys (and later, girls) who spoke the Queen’s English and read the English language newspapers. The constant rewarding and decorating of such patriotic Asian subjects of the crown – or “ornamentalism”53 – had an impact which was both stunning and effective. This group of local loyalists were courted on many sides and conferred with such dignity so as to elevate their status in the eyes of the administrators and the rest of the ruled.

|

|

SINGAPORE AT THE HIGH NOON OF EMPIRE

|

|

The British Empire reached her dizzying heights at the turn of the century, in 1900, before the horrendous tragedies of the two world wars. A significant portion of the world was in some way governed by Britain – as dominions, colonies, protectorates or territories. Still fresh in the hearts of those in the metropolis as well as in the colonies was the grand spectacle three years prior. In 1897, Queen Victoria had commemorated her Diamond Anniversary on the throne. Every celebrating English person had cause to smile smugly as he or she surveyed the world map on the wall, a quarter of which would be coloured red.

…their pride was understandable, as they contemplated their possessions that summer. It was a world of their own that they commanded, stamped to their pattern and set in motion by their will. Their flag was, if not loved, at least respected everywhere. Their ships lay in every port, and majestically moved down every waterway. Their trams puffed to intricate time-tables across the plains of Asia. Their armies stood to their guns in gullys of Chitral or barrack squares of Canada, their administrators ordered the affairs of strangers from Lagos to Hong Kong…. In every continent the Queen’s judges decreed lives or deaths, the Queen’s warships swanked into harbour and the sounds of empire echoed: hymn tunes, reveilles, halloos, sirens, rifle chatter, “Play the game,” from their schoolmasters and “Boy!” from the lounging planters. It was a stupendous surge of their own energy that the British were witnessing and it stood beyond logic or even self-control: as when a man suddenly realises his own strength and expects life itself to obey him.54

The strains of “Rule Britannia, Britannia rules the waves….!” were heard, sung and re-sung everywhere the Union Jack flew. Composed originally in the 1740s, the patriotic verses had been made even more popular by the deft inclusion into the plays of Gilbert and Sullivan, in 1887 – the play HMS Pinafore, celebrating the Queen’s jubilee – and even in 1897, rousing all at Victoria’s sixtieth year on the throne as “Her Majesty Victoria, by the Grace of God, of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland Queen, Defender of the Faith, Empress of India.”

With the Empire at its pinnacle, travelling within and even without her boundaries was at its height. Major colonies such as Singapore became more accessible by ship from Europe as well as Asia. This fluidity of movement into the small island had no little impact on social relations there.

By this time the population of the colony was around 140,000, filled with those devoted to acquiring riches and those who simply came to eke out a living. The official 1907 handbook to Singapore declared that the streets of the town were crowded, busy all day and all night. There were “carriages, hack-gharries, bullock-carts, and jinrickshas pass and re-pass in a continual stream.” There was never any shortage of hawkers or food: “native vendors of various kinds of foods, fruits, and drinks, take up their position by the roadsides, or, wandering up and down the streets,” all shouting, haggling and extolling the excellence of their wares. In summary, “all is bustle and activity.”55

The ethnic variety, so long a feature of Singapore life, remained colourful and diverse so much so that the colony was a veritable collection-pot of babble:

In half an hour’s walk, a stranger may hear the accents of almost every language and see the features and costumes of nearly every race in the world. Amongst the crowds that pass him, he may see, besides Europeans of every nation, Chinese, Malays, Hindus, Madrassees, Sikhs, Japanese, Burmese, Siamese, Javanese, Boyanese, Singhalese, Tamils, Arabs, Jews, Parsees, Negroes etc etc.56

With so many groups of the earth’s inhabitants living on a small island colony, it is no surprise that there was such a great variety of religions present. The bustle and noise that emerged from the streets of the native quarters mingled with the ceaseless sounds of religious fervour – the ringing of bells, rapid beating of drums and hum of chants. According to Isabella Bird, an astute Victorian observer, it was altogether, “an intensely heathenish sound.” And befitting the frenetic nature of the town.

And heathenish this great city is. Chinese joss-houses, Hindu temples, and Mohammedan mosques almost jostle each other, and the indescribable clamour of the temples and the din of the joss houses are faintly pierced by the shrill cry from the minarets calling the faithful to prayer, and proclaiming the divine unity and the mission of Mahomet in one breath.57

|

|

THE “CODE OF THE PUKKA SAHIB”

|

|

However, in truth, many members of the colonial society did not like to be at close quarters to the “indescribable clamour.” Being in the vast minority meant that it was often very overwhelming to live in a tropical island which was so hot and humid and so full of mystery. For them, many Asian rituals, habits, temperaments and vices remained unknown and difficult to understand. It was always far easier to rule and administer the masses from afar rather than from among them; to remain separate from the natives rather than to “go native.”

To be sure, this propensity to be detached posed a very real dilemma to the colonial elite. This was because by the late Victorian century, the British Empire was run by men and women who were also convinced that as rulers, or colonisers, they had a major role to play in the uplifting of indigenous and immigrant societies. How to resolve the conundrum of ruling and uplifting the Empire’s subjects without getting too close to them was the whole function of The Code of the Pukka Sahib.58

This code of conduct for the white man – or pukka sahib - in the colonies, though never explicitly defined or formalised, had certain marked characteristics that served to guide his behaviour in the home, within the European community and towards other races. All these were meant to separate, rather than integrate, him from the larger Asian populace whom he ruled. Europeans preserved their prestige by maintaining among themselves a higher standard of living than that enjoyed by other ethnic groups, and by staying aloof from the alien world all around. “Separateness was a technique of dominance.”59

A sharp sense of the alien surroundings the English were in was vital to the maintaining of the code. As late as 1934, Roland Braddell advised his son:

If you want to be happy, remember that the country is just around the corner waiting to blackjack you. Don’t admit that you are living in an oriental city; live as nearly as possible as you would in Europe. Read plenty… keep yourself up to date… have your own things around you, and as much beauty as you can in your own home. Above all, never wear a sarong and baju; this is the beginning of the end.60

The colonial community did their utmost to “live as nearly as possible as…in Europe.” An English woman arriving in the British colony of Penang, (so similar to Singapore) north of Kuala Lumpur in 1911, for example, would spend her day first at the Botanic Gardens, where the sycamores and sloping lawns would remind her of Wiltshire. Dinner and dancing in the evening was predictably at the E & O Hotel. Here the chef was European and the lady might well have been eating in London. After a night’s rest, the lady could climb Penang Hill, either on foot, on pony or on a sedan chair borne on the shoulders of Tamil labourers.

All was calculated to make the white man’s Penang as European as possible. Nothing was foreign here, as long as he did not look too hard. Most of the British did not. Yet much of Penang was foreign. Near the E & O hotel were opium dens and child prostitutes and a large leper colony. There was the temple close by with its deadly snakes. Even in the Gardens, lurking among the oaks and willows were ipoh trees whose sap was poisonous and clumps of nibong palm, the stems of which were used as blow pipes. This Penang the newcomer chose to ignore. Their Penang was “an evening of foxtrots and clarets.”61

What the British ate at home in Penang and Singapore was telling. For breakfast – oat porridge, bacon and eggs, tea, toast and marmalade. For dinner, typically tomato soup, cold asparagus, roast chicken, mashed potatoes and canned peas. The Planter often ran recipes for bread sauce, parsley stuffing, lemon tarts and Welsh rabbit. At Christmas there were instructions on how to make trifle, brandy butter and mince pies. As for strawberries and cream, if no strawberries were available, one could produce a realistic substitute by mashing bananas with plain milk. After mashing and beating this for a few minutes, “it will smell like fresh, crushed strawberries. Add two or three teaspoonfuls of strawberry jam to complete the illusion and place on ice for half an hour before serving.”62

The institutions the British built in Malaya were to be replicas of those at home in England. These included clubs, race courses, gardens and cricket fields. For the Englishman or woman who resided in Singapore, they could, if they had wanted to, choose to live as if they were still in England itself, among English people only. As late as in 1927, a Helen Candee would write concerning the colony:

You live there in an English hotel, with English people about you, and English motor cars driving up to the entrance below your balcony. Across the square is an English club, and standing within the wide stretch of trees and lawn is an English cathedral with English chimes that ring out the English hours.63

The British enjoyed life as they would have in England – with bridge parties, dinner and dance functions and tennis. All was designed to delude them into thinking they had never ever left England. “The British were master illusionists. Like that recipe for faux-strawberries, nearly everything they did in Malaya was designed to deceive.” The British quickly decided that there was only one way to survive in a Malaya they had to rule but did not fully understand: they had to stick together.64

And stick together they certainly did. By the 1880s, the invention of the steam engine had facilitated transport to the East. Many more Europeans came out, so that it quickly became easier for the colonial society to find friendship within its own circle. The necessity for inter-mingling with the local races diminished with time. And once a few Englishmen (and women) were gathered together they quickly found numerous ways to amuse themselves.65

One result of such increasingly introspective socialising was the growth in the number of hill-stations. In Malaya, the British often resorted to these places for rest and recreation. Short stays in these stations, located at Fraser’s Hill, Cameron Highlands and Maxwell Hill were sought after for escape from the perceived health hazards of the lowlands. The tropical climate, it was thought, had a negative effect on the English constitution and would lead to mental and physical disabilities. Since regular trips back to England were too costly, tours of duty in Malaya were punctuated by retreats to these increasingly popular hill-stations. “In short, one rationale for the development of hill-stations was that they obviated the necessity of a long and costly journey home by providing more accessible places with a benign, home-like climate that promised physical and emotional renewal.”66

A major component of the pukka sahib’s code of conduct out in the colonies, was therefore to remain separate from non-Europeans as much as possible.

There was to be no consorting with the Other. Do that and they risked, not just themselves, but colonialism as well – history’s great effort to forge a better world. The British had not come to Malaya to assimilate. Nothing would have been more detrimental to their purpose. They were the stewards of Judgment Day, destiny’s children, history’s chosen instrument, Malaya would assimilate with them.67

Edward Ingram has forwarded a fascinating argument that the colonial in his own corner of the empire lived in a daydream peopled by fantasies; the stability of his life was owed to the confidence that his daydream would not be interrupted. He was required to daydream, but could not decide what to dream about or when to dream.

The Code of the Pukka Sahib did not emulate the public school tradition of trying to turn out a certain style of man; it merely trained everyone to live as if nobody were around. One was asked to follow a strict, all-encompassing routine, and one’s success in following it was measured by an ability to stand still. The ideal Pukka Sahib never moved.68

We pause now to caution that it is dangerous to judge the Empire and its servants by the standards and values of the 21st century. Singapore, like most other colonial cities in the Victorian century, was pluralistic rather than multicultural. That is, local society was characterised by a strict occupational and social stratification along ethnic lines. There was little common interaction, except for the basic exchange for daily necessities.69 Even the geographical layout of the town area, dating back to Raffles’ time, still existed quite unchanged. There were separate quarters for the Chinese, the Arabs, the Indians, the Bugis and so on. There was no national identity as we would know it today. There was precious little to move or to bind the races together.

|

|

THE CONTRIBUTION OF COLLABORATORS

|

|